In the late 1960s, tuition at the University of Illinois—the flagship state school in the Champaign-Urbana metropolitan area—was a meager $400 a year. Tony Freda, a student and budding guitarist, transferred there from a private school in Miami, in part because of that fact. It was affordable enough, he soon realized, that he could pay his bills in full by playing gigs on the weekends at parties on campus and bars around town. He played first with a band called the Terminal Pros, named for the school’s policy of “terminal probation”—an academic punishment that meant failing grades the following semester would result in being kicked out of school. With upwards of 50 fraternities and sororities on campus, there was always a party to play, and they could take home as much as $50 a piece from those gigs. But the band’s name turned out to be prophetic. “Three of the guys flunked out of school,” Freda remembered. “They would come in on weekends, but it wasn’t the same.”

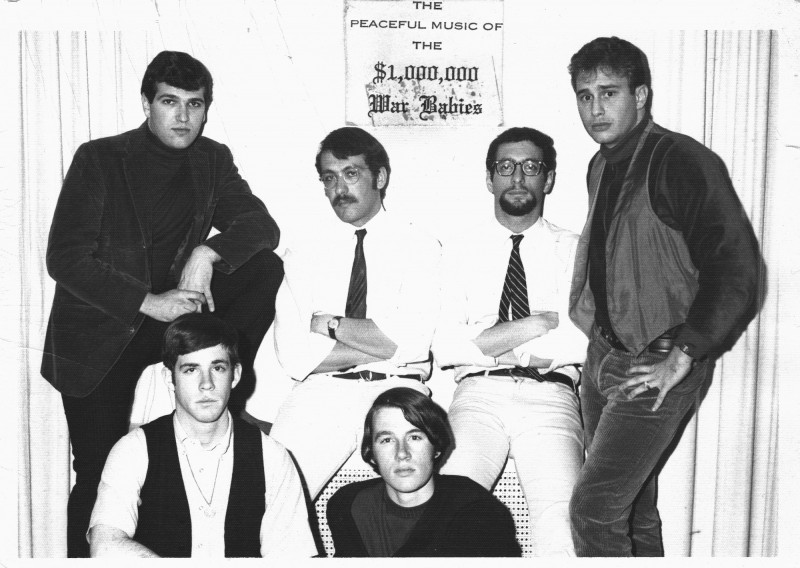

Freda needed the money for his tuition though, so starting another band was more or less a necessity. He found a couple more peers who played instruments and ripped a name from a newspaper headline that described his generation: $1,000,000 War Babies. It was a humble effort at first. A set of easy covers was thrown together, jamming out shambling versions of “Louie Louie” and, as Freda described it, “stuff you could dance to when you were drunk.” They were loud by design, in part because they had to be in order to be heard above the din of the fraternity row, but also because Freda was a true believer in the power of early rock n’ roll. “The music kind of drones,” he says. “It’s repetitive, so you can trust in it. It’s like a wave and when you ride it, it’s comforting.”

Their sound was a good fit for the frat life, which both Freda and multi-instrumentalist Marty Shepard described as “beer-fueled.” The $1,000,000 War Babies would set up on the floor of the common area of a house, and play to a rowdy crowd of dancing revelers, unraveling both beloved covers and a small handful of originals that—per Freda—would sometimes be the most requested in their repertoire. While the parties sounds far cry from the modern day hedonism that happens on college campuses, Freda remembers a few memorable pranks that derailed some of their gigs—like when one group of boys smeared ketchup on themselves and started screaming to stage a shooting, or when another group lifted a Volkswagen onto the front porch of the house, preventing anyone inside from opening the door and leaving.

Outside of a few key players—like Freda and Shepard—$1,000,000 War Babies were a constantly changing outfit. Even though they were only a band for just about three years, the lineup had more permutations than Freda can even remember. With the Vietnam War ongoing, there was a huge incentive to stay in school and avoid the draft. And while they were there, the kids needed to make some money, so the War Babies became an evolving crew of whatever non-professional musicians Freda could convince to show up for a little bit of cash. Shepard laughed when asked what qualities made a musician would be a good fit for the band. “Beggars can't be choosers,” he said. “It was more like ‘Oh my god, we have a gig and we don’t have a drummer, what are we going to do?’”

One of the more lasting permutations of the band included the singer Margie Sheaffer, a senior in high school in Chicago who was a good friend of one of Shepard’s cousins. Sheaffer says she hadn't been in any bands before, but as a theater kid, she always felt a magnetic pull to the stage in whatever form that took. “I was a weird kid, I’d be alone in the basement singing to no audience,” she said. Even though it was a totally new experience she took to it fast. Shepard said she quickly became a focal point of the band’s performances and image due to an “effervescent stage personality.”

The band didn’t publicly release much music, but their "Hey Little Boy” single is a shimmering document of Sheaffer’s time in the band. A garage-y ballad of desperation and longing, the track is full of the same sort of yearning honesty heard in the songs Ronnie Spector sang in the era. Sheaffer fondly remembers the studio experience because it allowed her the unique experience of having a duet with herself, but because of the studio’s limitations she essentially had to guess at her original vocal take while she doubled it and recorded harmonies. Any perceived imperfections only lend the recording a sort of ghostly wispiness, as though Sheaffer’s singing along with a version of herself in the spectral plane.

Shepard is sheepish about the recording now. He said when a family member asked to hear it recently he sort of shrugged it off as an embarrassing memory. But in it, he still hears a sort of “innocence,” that could have only come from that era of the music industry. “It does reflect back on those times when anybody, maybe, just maybe could write a hit song,” he reflected.

The $1,000,000 War Babies didn’t last much longer after the recording of that 45. Sheaffer left the band after less than a year, in part because the way she sang was making her regularly hoarse. She wouldn’t sing onstage again until she performed in a local Senior Idol competition in Pennsylvania in 2012.

Shepard, for his part, would become more entrenched in the rock scene in Champaign-Urbana that was quickly becoming a matter of national concern. He joined an early lineup of REO Speedwagon, who were then playing covers around the same circuit of pubs and parties that the War Babies were. He played trumpet and would often take the stage with a boa constrictor winding around his instrument as he performed. It was an exciting time, Shepard says, that kicked off more or less contemporaneously with the $1,000,000 War Babies, due in part to the fact that a young Irving Azoff was running the Blytham Ltd. management and booking agency. Shepard left REO Speedwagon before they rocketed to international success, but now he looks back on the period with a sort of cheery bemusement.

The $1,000,000 War Babies ultimately dissolved when Freda graduated from the University of Illinois. In some ways, the function of the band was done, since he’d paid all his tuition. But the war was still going on, so he ended up enlisting in the Air Force, which meant maintaining the band wouldn't be a possibility. “Over the years, it’s been really hard to find a group of people who want to listen to you as much as you want to listen to them," he said. He had that with the $1,000,000 War Babies, but it's been tough to find since. “You try to recreate that [feeling], but you can’t go home in certain ways,” Freda lamented. “It would be fun to hook up again though.”

- Colin Joyce, 2020