The life and music of Charlie Megira are more dream than reality, a reverie concocted by the mind in the throes of a fever, a welcome hallucination replete with beautiful settings that drip into basins of consciousness. His was a music both familiar and entirely alien at once. It touches on corners of darkness, an isolation both lonely and sweet, all wrapped in a cold glow that draws the listener into each note, each melancholy melody triggering unrecorded experiences.

Even in this age of near-total Internet accessibility, Charlie Megira is a modern mystery. A casual search turns up little aside from a few cryptic articles. His brief career unfolded during a changing of the guard in the music industry, opening on the death of the compact disc and ending just prior to Spotify’s IPO. For an artist like Megira, living far away from a major music outpost, there was more chaos than structure for his recordings to exist and find an audience. This collection is the first attempt at putting the pieces together, compiling a life’s work of an artist whose spark almost shined unto the world.

Through the twilight of the 1990s, Charlie Megira’s native Israel had been no land of milk and honey when it came to producing underground rock acts. Little in the way of interesting Israeli garage and/or psych rock had made its way the US since the late 1960s—when acts like The Churchills, Danny Ben Israel, The Fat & The Thin, and a dozen or so more made it across the Atlantic. The Israeli recording industry had always intentionally fostered its own sound, refusing to promote groups like The Everly Brothers and The Beatles in the ’50s and ’60s and instead cultivating a style of folk music that was nurtured in the kibbutzim and the desert. But such sonic isolationism had little hope of stanching the flow of rock ‘n’ roll, which bled through all borders to infect any and all cultures that sought it out.

Charlie Megira’s earliest recordings reveal a junction point between Link Wray’s surf guitar and the theatrical psychobilly of The Cramps. He saturated his six-string chiming with effects and delay, a timbre both ghostly and vintage yet fresh and ethereal. The fact that Megira sings in Hebrew only compounds the what-the-hell-is-this character of his output. His was a mystery far too intriguing to remain obscured for long.

Gabriel “Gabi” Abudraham was born in Bet She’an in Northern Israel, a deeply historic area that had been home to the Canaanites during the Bronze Age, the Israelites under David and Solomon around 1000 BCE, the Muslims a few hundred years after, and a host of disparate groups leading up to Israel’s founding in 1948. Gabriel Abudraham arrived in 1972. “King Solomon said that if there is a heaven, then Bet She’an is the gate where you will enter it,” he told The Stranger in 2014. “Actually, though, there was something funny at the entrance of the city not too long ago—the sign that said ‘Welcome to Bet She’an’ [was covered by] a sign that said ‘Welcome to Texas.’”

“The water there is sweet,” he’d later say of his hometown. “As a kid I used to collect wild dogs and paint them with black stripes and run into town. I saw a crow spit on a cat.” In those same formative years, the late Jo Amar and Salim Halali entranced Abudraham with Moroccan celebration music. But his discovery of Elvis and Sun Records, The Smiths, Johnny Thunders and T-Rex altered his listening trajectory significantly through his teens and 20s.

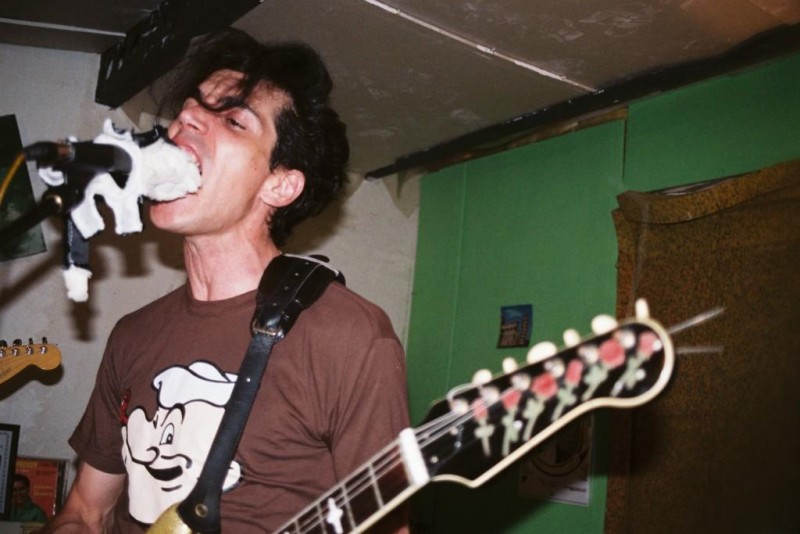

In 1993, Prime Minister Yitzak Rabin and Yasser Arafat signed the Oslo Accords, ushering in the hope of peace between the Palestinians and the Israelis. When Rabin was assassinated on November 4, 1995, by a right-wing extremist, a darkness fell over the land. In this black night of the Israeli soul, a movement began to take hold. Two weeks after Rabin’s assassination, Israeli journalist, musician, and filmmaker Boaz Goldberg began hosting the “Glory Nights” parties at the Golem Club in Tel Aviv, featuring mod DJ’s to attract countercultural kids who hadn’t found a fit in any other local scene. Goldberg booked musicians who fit the same bill, including the 23-year-old Abudraham, who’d just finished his mandatory three-year stint in the Israeli army as a cook. Having played guitar for just a few months, he formed The Shnek with mutual Memphis rock enthusiast and singer Natan Gruper. During their first performance, Abudraham was hit in the head with a beer bottle—and then proceeded to play on and bleed on until his eventual collapse.

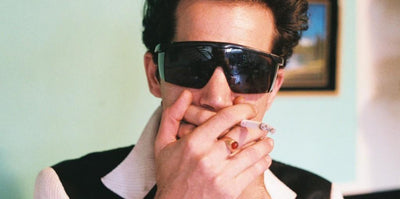

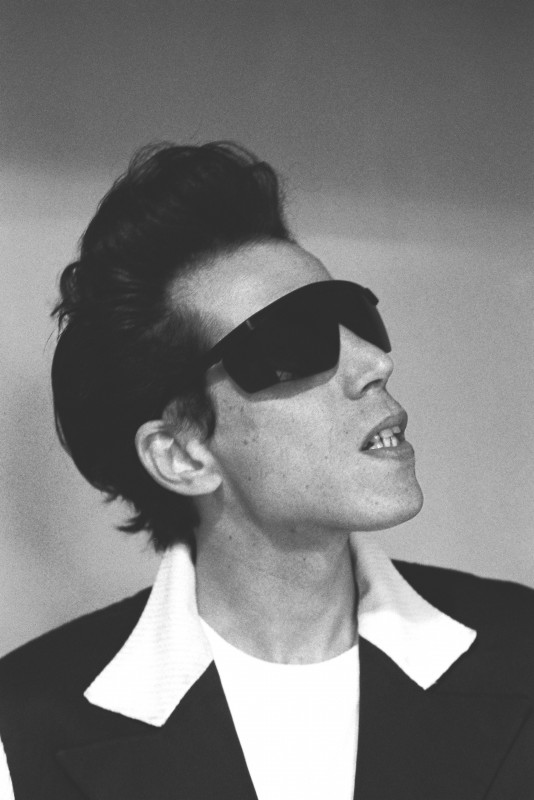

By the turn of the century, The Shnek had disbanded. Abudraham continued to work, cocooning himself in a makeshift studio inside his Tel Aviv apartment and crafting the Charlie Megira alter ego for the performance of his new compositions. He’d borrowed the “Charlie” from another dark pop head trip of 1960s conflict: “Charlie don’t surf!,” Colonel William Kilgore’s famed dismissal of Viet Cong forces in the 1979 film Apocalypse Now!. The Megira surname was his mother’s maiden. He’d add a costume featuring pointed shoes, a lightning bolt lapelled suit, oversized shades, and a wild black Jim Jarmusch-style pompadour that stuck with him for the rest of his life. His hope had been to “revive a past that never existed,” he said.

Charlie Megira released his debut record in 2001, the enigmatic and bewilderingly-titled Da Abtomatic Meisterzinger Mambo Chic. A 23-minute lysergic Roger Corman 1950s dreamscape, Mambo Chic pays loving homage to the backseat make out pop songs of that era. “Tomorrow’s Gone,” its signature track, best exemplifies the mystical vision of Megira: a rhythm guitar lazily strumming out a stoned and watery lead, and a Hebrew crooner falling in love while falling asleep, his languid melody seeping out atop the surreal music he recorded in his bedroom.

“Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow” opens with a crunched rhythm guitar that hints at the sonic power Megira would soon unleash, but quickly pivots into a muddy tip-of-thehat to Santo & Johnny’s international megahit “Sleep Walk.” Seemingly named after some lost, low-budget ’60s Ray Dennis Steckler drive-in horror flick, penultimate album track “The Death Dance of the Busty Hot Lifeguard Instructor Babe” celebrates that era’s trash culture with a zombified tiki club tour de force, complete with wild twangy guitar soloing throughout and a bongo beat that sets it way, way out there in caveman country, stranded in the jungle, never so much as looking to get back to The States.

Charlie Megira aggressively maintained the purity of his artistic vision. In an interview with Boaz Goldberg, Megira once lamented that “Israeli rock is too staged.” Instead, he sought to tap into the core of something real. He sighted Mizrahi music, sung in Hebrew by Jews who had come to Israel from other parts of the Middle East. Zohar Argov was the “King of Mizrahi” music, a hero of the genre. After he hung himself in a jail cell at age 32, his demise propelled him to legendary status in Israel. Like Argov, Charlie was determined to live and breathe his musical vision.

By this time, Charlie had met and begun dating Michal Kahan, an active singer and guitarist in the Tel Aviv scene. He’d been introduced to Kahan by Goldberg, who had dated her years prior. Kahan joined Charlie’s band on guitar and the two moved in together. In late 2006, Charlie Megira Und the Hefker Girl appeared as a self-released CD with a D.I.Y. cover featuring silhouettes of Megira and Kahan. The 12-track album found Megira entering a world of gothinflected post-punk. “Fear and Joy” abandons his surf-rock reverb for the same cold, metallic production that launched a plethora of early ’80s Joy Division clones out of England. And while “Nothing” truly echoes the memories of a make-up drenched Robert Smith, “Kiss of Death” shows Megira reemerging from his private UFO to create a Sonic Youth-ian noise-scape, with Kahan conjuring a low-fi Siouxsie Sioux vibe behind the microphone.

I was first introduced to music of Charlie Megira a little after the turn of the century. It was at a Gris Gris show at the Stork Club in Oakland, California, where Israeli transplant Eran Yarkon handed me a CD-R of Charlie’s debut album. The disc was wrapped in a dirty, folded 8 1/2” x 11” piece of paper, crisp to the touch. In his thick accent, Eran implored me to listen to his friend Charlie from Tel Aviv and to consider releasing it on my Birdman Records label, which after repeated listens, I did.

I met up with Charlie while in Israel in 2007, just after the release of Hefker Girl. He and Kahan were living in Jaffa, a blown-out section of southern Tel Aviv that was then, and remains, a magnet for artists, with cartoonish murals decorating alley walls, and Arab flea markets overflowing onto the streets. Charlie met me on his street corner, wearing his shades, looking more gaunt than I’d expected. His skeletal visage matched a set of oversized disorganized teeth with a careening, spindly gait.

His apartment was filled with musical instruments, records, and books stacked everywhere, save for the floor-to-ceiling windows that overlooked his ancient, grey, and misty neighborhood. He lit incense and we sat in the middle of the room on a dismal brown couch. He introduced me to Michal who asked me what time of day I was born and what star I was born under. For the next hour, she led me on a seer’s journey through my past romantic history into my future, telling me the detailed story of how I was soon to meet the woman who would become my wife. Charlie lit cigarette after cigarette, shades always on, telling me to listen to everything Michal said.

And everything she said came true.

As the sun went down, Charlie opened up about his musical world in Israel. He didn’t feel at home in the country of his birth—he didn’t understand the government, didn’t fit in with the people, and was overly cynical about his environment. He had found freedom as an outsider, regaling me with tales from his crazed club days, in which a handful of people would witness the musical anarchy he’d unleash under different band names and line-ups: three-piece combos, amps turned all the way up, blasting noise through the walls like bombs dropping all around, leaving the audience completely shell-shocked. He unfurled these stories with a satisfied grin, ending with the new ideas he was about to try next.

In 2008, Charlie Megira and the Modern Dance Club was formed. At Charlie’s behest, Kahan moved from guitar to drums and the group was rounded out with Tal Fatale on bass and Javi Scheiner on rhythm guitar. With the Modern Dance Club, Megira enjoyed his first proper LP release and logged his first European tour. And it would prove to be his most assaultive project to date.

The Love Police album was first released in 2009 as a single LP on Germany’s Burnout Record Store label and then again in 2011 as a double LP on Eran Yarkon’s Guitars and Bongos Records of Oakland, California. The album showcased a grungier, more driving vision of trashy post-punk, with Megira snarling in English over a gut punching wall of crazy electric guitars. “Elvis Is Not Dead” captured a new, unchained Megira, screaming lyrics about whores while attacking his guitar with vicious, methodical abandon. Love Police confronts the senses, from the racially and sexually provocative cover to the distorted, screamed vocals within. Megira would later confess that the album was heavily influenced by San Francisco hardcore outfit Millions of Dead Cops.

Yet just as Megira was harnessing momentum with the new band, he’d hit a rocky patch with Kahan. Since the beginning of their relationship, Megira and Kahan had been in lockstep with each other as lovers and as musicians. Like Lux and Ivy of The Cramps, Charlie and Michal made for an amazing rock ‘n’ roll spectacle: he the alien rock star and she the talented vixen with an attitude. The break-up, which happened on Charlie’s 38th birthday on October 10, 2010, was the end of a significant chapter in Megira’s career.

At this point, the story evolves at a faster pace: by 2011, Megira was married to Seurat (Sash) Samson. The two had fallen in love soon after meeting in a South Tel Aviv bar and not too long after, Samson was pregnant. In November of 2011, Megira and a four-months-pregnant Samson had a large, traditional Jewish wedding ceremony and, in May of 2012, welcomed a son named Adrian.

Within months of Adrian’s arrival, the Megiras announced that they were leaving Israel and moving to Berlin. While Charlie had always been an outsider figure in the land of Israel, he had a strong connection to his family and heritage and the move shocked everyone around him. He thought himself too old to continue a career in music, seeing the move as an opportunity to focus his development as a chef and a painter.

But even so, midway through 2013 and after a short “hiatus,” he formed The Bet She’an Valley Hillbillies, named after the homeland he’d recently left behind. The group comprised The Modern Dance Club’s Tal Fatal on bass, who was also living in Berlin, and Stefano, described by Boaz Goldberg as “a bongo-beating beatnik Charlie met in German language studies class.” The Bet She’an Valley Hillbillies was a return to form for Megira, a sojourn back into his earlier musical fascination with late 1950s and early 1960s rock ‘n’ roll.

While the Hillbillies tallied a revolving door membership roster over the next few years, the act also recorded The End Of Teenage, an album’s worth of songs released on cassette only by Guitars and Bongos in 2014. While Megira keeps an Ian Curtis croon in his back pocket, his delivery on Teenage is not as aggressive. Opener “Jack The Ripper” has a great drive to it, but is also almost raga-ish, with Megira displaying his hypnotic surf guitar backed by a bongo beat.

During this period, Megira’s music found its way to Israeli filmmaker Ari Folman, then fresh off his Oscar nomination for Waltz With Bashir and at work on his next project, 2013’s live-action/animated The Congress. Folman brought Megira in to write music for the film, alongside legendary composer Max Richter. Folman’s film also made space for a party scene in which Megira and his backing band entertain a glitzy ballroom attended by cartoon renderings of Elvis, Picasso, Sinatra, and other luminaries.

In 2014, Megira brought The Bet She’an Valley Hillbillies to America for a short trip down the west coast, plus a stop at the Austin Psych Fest. “On this tour, I sing in English, and also in Japanese, Arabic, German, and the holy Hebrew language,” Megira told The Stranger. “I feel pretty comfortable with any kind of language. Rockabilly is all about dealing with the normal in an exotic manner. I think everything that diverges from this rule should be considered to be a crime against rock ‘n’ roll.” It was on this trip where his legend as a visionary outsider finally began to grow.

Another tour of the States garnered new fans including Shannon & The Clams, The Black Keys, and The Strokes’ Julian Casablancas, who approached Megira about signing with his own Cult Records label. After fourteen years of releasing records, Charlie Megira was on the verge of breaking through.

For much of 2015, while awaiting the fruition of the deal with Casablancas, Charlie lived in Asheville, North Carolina, after which he moved back to Berlin. In 2016, he returned to Israel for three gigs. His iconic pompadour was gone, and he looked gaunt, even by his own standards. And while his return to his homeland was well received, he spoke about no longer making music and retiring the Charlie Megira character. His June 16, 2016, performance at the Tel Aviv Cinematheque would prove to be his last.

Megira had attempted to commit suicide at least two times during the 1990s. According to Samson, he would suffer periods of confusion, stretches during which he could not connect with reality, when he’d be unable to recall major life events such as the birth of his son. He had long wrestled with an inner darkness about that he could not escape—not as Gabi Abudraham, and not as Charlie Megira.

As 2016 wore on, Charlie returned to his life as a father and chef in Berlin. The Casablancas deal, if it had ever been at the precipice of reality, never materialized. Max Richter, whom Megira had remained in contact, attempted to usher him toward a record deal, but to no avail. According to Samson, this was during one of Charlie’s periods of confusion. On November 5, 2016, Megira hung himself in his Berlin apartment. When he was found, his guitar was plugged in, his effects pedals were on, and his amp was buzzing. He left behind a wife, a child, and a growing flock of fans the world over.

Charlie Megira was buried in a Jewish cemetery in Berlin. A dark stone obelisk marks his grave, with one of its faces engraved in gold in remembrance of Gabriel Abudraham. An adjacent face is engraved in memory of Charlie Megira, a testament to an artist who chose to live two lives: the one he was born into, and the one he invented: a creation for the world to witness. Below the gravestone’s Charlie Megira inscription are five words, a phrase from an interview of the artist himself, that reveal everything about who he was, is, and will ever be: “A sun shining backwards.”

—David Katznelson, June 2019