Somewhere in the rolling cypress hills of rural Sonoma County, California, a box of old crystal wine glasses sits, collecting dust. Probably a common sight here in the heart of California’s wine country, these glasses aren’t particularly special. They aren’t rare or collectible; they were never used to toast to some important figure. But to their owner, David Casper, these glasses are a portal to inner space.

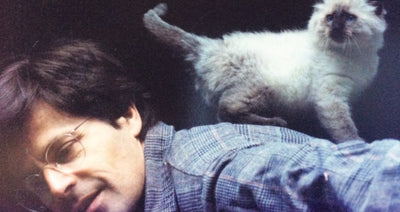

David Casper is a musician, permaculturist, and spiritual seeker who, throughout the 1980s, created a series of records and tapes exemplifying the most poignant and sublime qualities of the American private issue new age canon. His is a discography of organic quietudes that are deeply grounding and rewarding experiences, and sound like little else made then or since.

Casper grew up on the south side of Chicago in a house filled with thousands of records — folk, classical, and jazz from around the world — collected by his father. As a child David began picking up instruments: a jaw harp first, and later harmonica and guitar. At eighteen Casper took an interest in the sitar, and started taking lessons from an old man in a Hindu living community in his neighborhood. He moved to Marin County to study under Ali Akbar Khan, the world-famous sarod player, at his renowned Ali Akbar College of Music.

“I think I came into [new age music] through Indian music,” Casper said recently. “Indian music has a meditative or contemplative phase in it — if you’re developing a raga, a lot of it is fast playing and so forth, but it often starts with a very slow, meditative part. That’s what tuned me into playing in a spatial way, without a beat. That’s kind of what I got into—to feel the space of music without the tyranny of a beat... It was the reintroduction of space—space that gives the mind time to think, and to contemplate, and to envision, because you aren’t being moved along at a certain tempo. That’s one of the things that new age music did: it filled a little bit of a void where there wasn’t really very much music that did that.”

After several years under the tutelage of Ali Akbar Khan, Casper moved to Seattle to continue studying sitar at the University of Washington. There he began to carve a niche for himself as a musician with expertise in non- Western instruments. He began to learn the zheng, a Chinese plucked string instrument that he would later use on almost all of his records, and would spend nights playing zheng and sitar in restaurants around the city. He made enough money to assemble a modest basement studio, where he would learn the basics of the recording process and engineer records for others. More importantly, though, he was finally able to put to tape some ideas of his own.

Casper’s first recording effort was an eccentric seven-inch under the name Cracky. “That was actually inspired by the eruption of Mt. St. Helens in 1980, less than a year after I got my studio going. It was the volcano talking,” he explains. “Pack A Punch” and “Coming Home Again” are two jaw harp / zheng / mantra-driven rhythmic miniatures reflecting a young, erupting musical mind, a world of musical possibilities newly at his fingertips. “Part of my goal was to create new combinations of sounds,” he remembers. “When you hear a new sound, it kind of does something to you.

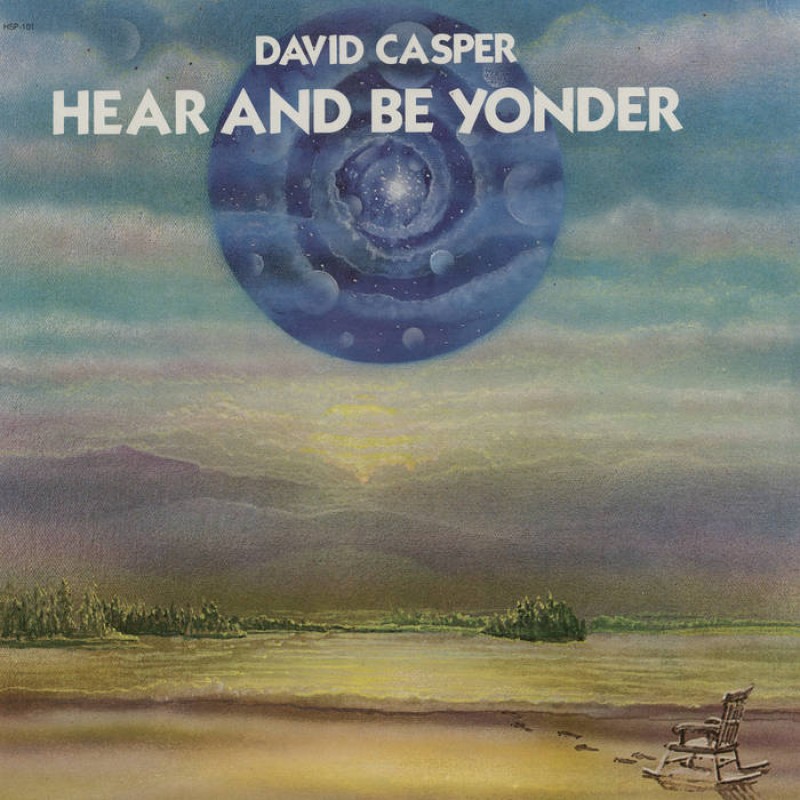

He realized his first full length in 1981, a soft coalescence of manifold instruments and traditions called Hear And Be Yonder (released, like the rest of his discography, on his own Hummingbird Records, unrelated to Joanna Brouk’s label of the same name). Through its transcendent use of sounds usually heard in more vernacular or culturally-specific traditions,Hear And Be Yonder was a means for Casper to create and explore, as he puts it, “new inner spaces.” This record is defined by a light, rhythmic weaving of instruments and forms that aren’t often heard together. Borrowing from musical traditions from Indian classical music to Appalachian folk music, Casper allows instruments as diverse as zither, tabla, kalimba, slide mandolin, jaw harp, harmonica, sitar, thumb piano, cello, ocarina, and his beloved zheng to coexist alongside one another. “I wasn’t only trying to be meditative; I wasn’t thinking, this is going to be a new age meditation album: [rather], this is an introduction to the range of musical spaces that I was exploring.”

As the title Hear And Be Yonder implies, this record intends to evoke and describe places both real (“Carmel Valley Sunset ,” “John Muir Trail ”) and imaginary (“Grasshopper Ridge,” “Skies Of Freebondaymia”). “I always felt like my music is visual,” Casper says. “I think of places I’ve seen, and then how those spaces translate into sound through me. That’s why [those songs] have those place names.”

If Hear And Be Yonder captures Casper depicting terrestrial beauty, his sought-after 1984 record Crystal Waves is a document of cosmic awe. Hear And Be Yonder’s shorter, melody-adorned vignettes evolve to be looser and longer; their components, now unshackled from rhythm, begin to describe something not yonder, but inner. But where many of his contemporaries employed synthesizers and other electronic means, Casper devoted himself to something more “consonant with [his] own heart”—large, immersive soundscapes from organic, acoustical sources.

“I was trying to have sounds that had a fullness within them that were kind of like food,” Casper explains. “Food for the brain. I felt that was more easy with acoustical energy and that the uniqueness of the moment would come through. In my music I wanted every moment to have its own quality... I wanted all the vitamins in there.” To this end he utilized tape manipulation and an array of finely tuned crystal wine glasses to develop a complex, overtone-rich pool of constantly undulating vibrations. “I would play a single glass with full attention for 20 minutes,”Casper remembers, “and when I stopped my head was going *ZOIOIOING*! It put me in a completely different state just hearing that one pitch and only that one pitch for 20 minutes. And [on] the next track I would play the next note of the chord I was trying to build, so then I would have this chord, each note on a separate track. Then I would blend that into a stereo [mix] by playing the faders so that the tracks would slowly weave in and out of each other. It was a very time-consuming project to make things that way.”

On the A side, the glass vibrations are more like habitations for improvised soundings from marimba and h’siao (a Chinese bamboo flute) from Windham Hill pillar Scott Cossu, T’ao Chu-Shen plays a ch’in (a Chinese plucked instrument), and Jami Sieber provides cello. The B side of the record features emanations from up to thirty glasses at a time. (“It’s all crystal!” the cassette cover proclaims.)

A guiding force that propels Casper’s work is a philosophy of sound that privileges the singularities and intricacies of each individual moment. Give each note “full attention for every second,” Casper instructs, and one allows that particular moment in time to express itself. He can point to specific moments on the B side of Crystal Waves that affirm this approach. “How I got those deeper bass tones, that was like a gift from the Gods!” Casper recalls that “it was an accident! What that was was recording the lowest pitch I could get on the brandy snifter at higher speed and then playing it back at lower speed. But, something happened with the noise reduction, I forgot to turn it on or off, I’m not sure which, but it resulted in the timbre getting really juicy, and it was exactly what I needed. It came down out of nowhere, and made the album work. And I don’t even know if I would know how to make it happen again.”

Following Crystal Waves came the meditative and occasionally outre Earthsight in 1986, and Primal Peace and Let The Earth Be Happy in 1987, two more signature explorations of novel instrument pairings. He also played piano, thumb piano, sitar, and zheng in Second Nature, a five-piece with one LP, 1987’s all-acoustic jazz / avant / world Natural Selection. 1997’s Unwraphas gone virtually unheard—“too avant garde, too experimental,” according to Casper. It would be his last new release for some time.

Casper spends these days cultivating a permaculture “food forest” in rural Sonoma County. He’s excited, and so are we, to share the news that for the first time in years, there is new David Casper music in the works, featuring a new instrument— the guitar. “I got interested in all the timbral aspects of what an acoustic guitar could do,” Casper says. “The guitar has all these colors and textures and there’s so many ways to play a note. I got intrigued with that, so I started playing more and developed a body of pieces that I’ll use to hang the other instruments onto; instruments I’m playing or have played throughout my life.”

He explains that it feels a lot like coming full circle in his musical life. “A lot of the same instruments on Hear And Be Yonder are on this album, but the guitar will be the bones of the piece. It’s got a lot of rhythm in it — after that, I want to do another album like Crystal Waves or Tantra- La.” Casper admits that he isn’t exactly looking forward to dealing with modern recording technologies and distribution models. Nevertheless, an optimism seems to accompany the resurgence of interest in the private issue new age which has some celebrating his work, even Casper himself catches only the slightest glimpse of it.

“I often wonder what the relevance of what I did is now,” he reflects. “I tried to come from the deepest space I could, and hope that comes across, and that it helps somebody to feel peace or open a door inside their own consciousness in some way. As a musician we have dreams that our music can affect people profoundly. Maybe once in a while it does.”

Written by Erik Kramer, a researcher and musician living in Madison, Wisconsin.