In the past it’s been called Terminus, The Gate City Of The South, Dogwood City, The City Too Busy To Hate, more recently The ATL, and always Hotlanta. But despite also being called the Black Mecca, Atlanta produced a relatively small batch of black records. Citizens of the greater metropolitan area can tell you about the Hooch, the Big Chicken, Little Five Points, Spaghetti Junction, and Gwinetians, but ask them where Record Row is located and they’ll likely respond with a shrug.

The first half of the 20th century was a productive time for black business in Atlanta. In spite of oppressive Jim Crow laws, black entrepreneurs founded the first black-owned newspaper, the largest black-owned insurance company, and dozens of hotels, office buildings, and restaurants in the “Sweet Auburn” district. A number of prestigious educational institutions filled Atlanta's black neighborhoods, led by Booker T. Washington High School, Morehouse College, Morris Brown College, and Atlanta University. By 1960, Atlanta was cemented as the heart of the “Chitlin Circuit,” when venues like Club Poinciana, the Builders Club, Magnolia Ballroom, and, of course, the infamous Royal Peacock reached their prime. Marginalized by uptight whites with one foot out of Fulton County on their way to suburban bliss, black record producers turned inwards, inadvertently changing the course of the entire Atlanta record business. Isolated from white entrepreneurs looking to cash in on the burgeoning R&B market, labels like T&L, Esprit, Hunter and Midtown popped up but, without access to white-owned radio and distribution, found themselves unable to compete outside the Perimeter.

For the better part of two decades it was nearly impossible to get a hit record with a hometown logo. Michael Thevis’s Aware and GRC labels managed a few between Loleatta Holloway, the Counts, and Ripple, but most of the charting records by Atlanta artists carried the mark of a major or major independent. Wendell Parker produced for Decca and his Shurfine label leased to Josie; Mighty Hannibal had minor successes on Josie and King; the Tams charted for ABC; Blind Willie McTell recorded for Atlantic; Duke Pearson produced and recorded for Blue Note; and Piano Red hit with “Dr. Feelgood” on Columbia while his guitarist Roy Lee Johnson went solo for Columbia subsidiary Okeh. Jesse J. Jones’s trajectory would follow a similar, though less fortunate, curve.

Jones spent a decade on the west coast operating the Lita, Morocco, and 4-J labels from 1957-1967, returning to his native Atlanta following the collapse of 4-J and a spell hiding from debt collectors. After settling in, he founded the newly minted Tragar label in 1968, the name sharing syllables with Jones’s wife Tracy and his eldest son Gary. He opened an office at 799½ Hunter St. N.W. in the West End—the cultural core of Black Atlanta—down the street from the best nightclubs and smack dab in the middle of four major black colleges, the location couldn’t have been better for recruiting talent. And while early singles by Tokay Lewis, Tee Fletcher, Chuck Wilder, and Frankie and Robert made minor impacts locally, a powerful voice was about to walk through his door and take Tragar national.

Born in Opelika, Alabama, but raised in both Birmingham and Atlanta, Eula Cooper was the artist Jesse Jones had been waiting for. Beautiful, articulate, and headstrong, Cooper had an incredibly adept command of her voice, green though she was. Cooper was trying on clothes at the boutique downstairs from the Tragar offices when she giggled her way through “Shake Daddy Shake” for her friends. The shop’s proprietor suggested she take the song to the guy on the second floor. Cooper and her friends marched upstairs to find Jesse Jones sitting behind a small desk in a paneled office. After her performance of “Shake Daddy Shake,” Jones immediately sent Eula home to fetch her mother. A child of divorce, Jones would become something of a father figure to her over the next four years, as she would spend all her time between Booker T. Washington High and the office, studio, or stage. Jesse Jones believed that Eula Cooper was the best chance they had for hit status outside the city.

“Shake Daddy Shake” seemed to prove that hypothesis, immediately finding a place on the local charts. Regional radio promoter Charles Geer began pushing the single outside of I-285’s loop and even convinced Atlantic Records to license it for a national run. Neither “Shake Daddy Shake” nor “Heavenly Father” had the legs or production values to jump state lines, but this would hardly be Eula’s last foray into the studio. At fourteen, it seemed she had plenty of time to crack the charts.

As 1969 rolled in, Jesse Jones was finalizing the second Eula Cooper 45. The two had spent most of the fall in the studio working on a handful of tracks, but “Try” was the clear standout. Tommy Stewart’s arrangement was impeccable, a simple melody taped out on glockenspiel for the introduction lead to a mid-tempo soul jam with royalty written all over it. For the b-side, Jones went familiar and used a note-for-note remake of Martha Reeves & the Vandellas 1965 hit “Love Makes Me Do Foolish Things.” It was built for chart movement but Tragar’s meager turnover left Eula Cooper’s best shot lost in the shuffle. The final 45 to carry the Tragar script was a Eula Cooper recycle job. Jesse Jones believed so firmly in her abilities that he took her under-promoted third single “I Can’t Help If I Love You” on the back of the key-vamped “That’s How Much I Love You.” Both songs were good, but missed the ingredients that made the first two Cooper singles great. Amid continuing lack of success, it made no sense to push forward on the same path. By the middle of 1969, the lights on Jesse Jones productions were turned off and the Tragar label retired.

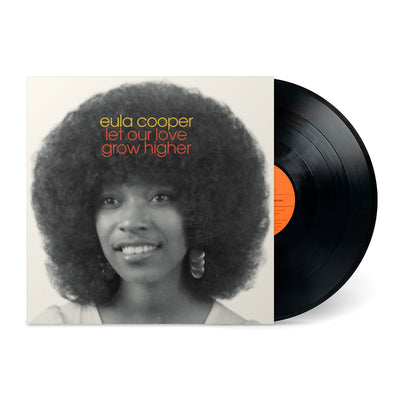

For the rest of 1969, Jones continued to work his artists on the regional chitlin’ circuit, booking and promoting their live shows. A real estate agent who had helped him with some of his credit problems was poking at the edges of the record business, and Jones could only oblige, founding the Super Sound label in early 1970. With a new infusion of cash, Jones made a move that was long overdue: he took Eula Cooper and band out of Atlanta into an entirely different world of recording quality at Muscle Shoals Sound Studios. For Jones, sweet relief was being back among true professionals, surrounded by the sound that superstars trekked the globe for. “Let Our Love Grow Higher” is eons away from any of Eula’s prior sessions. That it missed the charts can only be attributed to a lack of promotion. Whether the records washed out or the housing market dried up, funding for Super Sound was done for after follow up flops by Bobby Owens & the Diplomats and Sonia Ross.

Addicted to record producing, Jesse Jones fired up his third label in as many years in 1971: Note Records. With Muscle Shoals churning out hits every week, Jones was convinced that his smash lay in the hands of the studio’s crack session men the Swampers. The first single on Note was Eula Cooper’s “Standing By Love”—a left over from the “Let Our Love Grow Higher” sessions—backed by the heart-rending ballad “I Need You More.” As the calendar switched over, Jones dragged Cooper into Melody Recording in Atlanta for the Bobbie Gentry-style story song “Mr. Henry” and slapped “I Need You More” on the back, but the results didn’t change.

Now a senior in high school, Eula Cooper was performing often and recording occasionally. She spent spare time singing in the choir, leading to the formation of the Cherry Blend with two choir friends, Shari Billingslea and Deborah Tolls. The trio recording of “Love Is Gone”—a sultry ballad in the Honeycone vein— prompted King to pick it up for a national run. Unfortunately, the girls, including Eula, had dispersed to different colleges and the group wouldn’t be able to support the single. Jones squeezed two more singles out his stash of Cooper recordings; 1973’s “Beggars Can’t Be Choosey”—recorded at Fame Studios with Sam Dees behind the board—was paired with “I Need You More,” but the third time was hardly a charm. “Standing By Love” was recycled as Note 7210 in 1974 with “My Man Is More Man (Than You’ll Ever Be).”

Note stumbled into the disco age, issuing quality singles by Richard Marks, the four Tracks, the Young Devines, Tony Troutman, and Clinton Harmon before shuttering in 1976. Jones returned to Los Angeles and opened a ceramics studio and lived a simpler, though admittedly happier life. Eula Cooper and Jesse Jones re-teamed in 1984 for “Feels So Right” b/w “You’re The Best” on his short-lived Adventure One label. It wa the final record to bear the name Eula Cooper. These later recordings live outside our story, which in truth remains a resident of Atlanta—a chapter in the city’s micro-music business lost among the kudzu and Coke bottles no more.