Riding the crest of West Hollywood’s break into Beverly Hills and covering a modest 2.7-mile stretch of California desert in concrete, Doheny Drive is both a repercussion of and a monument to Edward L. Doheny’s massive oil fortune. It rumbles from as far south as Canfield Avenue Elementary and intersects the boulevards of Pico, Wilshire, Beverly, and Santa Monica, buzzing by the Troubadour and Elektra Records’ earliest office building. The thoroughfare then loses itself in twists and turns before disappearing into the Hollywood Hills north of Sunset—a fitting metaphor for the dominant Doheny family and its Los Angeles notoriety, which waned just as the Strip exploded in the mid 1960s.

Other Southern California landmarks bear the Drive’s petroleum-built Irish surname, notably USC’s Edward L. Doheny Jr. Memorial Library, Orange County’s Doheny State Beach, and the Doheny Mansion on the campus of Mount St. Mary’s College. Completed in Beverly Hills in 1928, the Greystone Mansion—Edward L. Doheny’s $3-million-dollar wedding gift to Edward “Ned” Doheny Jr.—never assumed the family name, though its 55 bedrooms and 46,000 square feet were the site of Ned’s 1929 murder-suicide, still among the great unsolved mysteries of old California. Far less mysterious, and much less conspicuous, was Patrick “Ned” Doheny’s turn at adorning LA infrastructure—for two weeks of 1973, as a modest bit of signage outside Tower Records at Sunset & Horn, just blocks from his namesake Doheny Drive.

“My family had no stomach for notoriety,” Edward L. Doheny’s great-grandson recalled. “It had never served us well.” Ned Doheny’s name may’ve opened plenty of garage doors along the road, but his boyish charm and natural musical aptitude got him through just as many front doors. Signposting Ned’s sojourn through the LA recording industry of the 1970s were Jackson Browne, Glenn Frey, Don Henley, Chaka Khan, Graham Nash, “Mama” Cass Elliot, Bonnie Raitt, and David Geffen—each a household name both inside and far from southern California. And while no bust of Ned Doheny appears alongside those of his Laurel Canyon brethren in the pantheon of classic rock, it’s due to no lack of songwriting or recording chops. Ned’s roadblock was inertia. “I was never sure if I was good enough,” he said. “I have a tendency to over-think things.”

The Early Bright

The second child of Stanford sweethearts Patrick and Patricia Doheny, Patrick “Ned” Doheny was born in March, 1948, seven years prior to the passing of Doheny family matriarch Estelle, widow to Edward Sr. Never particularly musical, Edward had furnished Chester Place with its first performance instrument: an opulent custom-built 1902 Steinway, every filigreed square-inch of it gilded in 22-karat gold leaf and replete with cherubic twin busts of Ned the First flanking the keyboard, plus an image of Estelle and the manse painted onto the lid’s underside. But that ornate—and frankly intimidating—set of 88 would not be Patrick “Ned” Doheny’s noisemaker of choice. “The guitar showed up under the Christmas tree,” Ned recollected of one fateful 1957 morning and accompanying its $34.95 Harmony California. “If my parents had known what they were doing, they probably never would have purchased it.”

After trading up from acoustic guitar to electric, young Ned Doheny quickly eschewed his instructor’s repertoire of novelty and folk songs. “I fell in love with the music I was hearing on my clock radio,” he confessed. “At one point, I was in the laundry room, and Elvis was playing on the radio. For some reason, my guitar and the radio were in tune. That just made my eyebrows disappear.” As the wholesome 1950s gave way to the turbulent early ’60s, Ned caught the surf bug, parlaying the sounds pouring out of Hawthorne’s Wilson boys and Tacoma’s Ventures into the Cajuns, a pick-up combo that rode the Echoplex and Fender Jag combo to dance slots at Coldwater Canyon’s Harvard School for Boys. But Ned’s Cajuns wouldn’t make it past graduation.

“Los Angeles was still a small town in the mid-’60s,” Doheny said. Kacey, Ned’s older sister, had become fast friends with Candace Bergen, then fresh off her 1966 big-screen debut in Sidney Lumet’s The Group and living with producer Terry Melcher in Benedict Canyon. Melcher’s hot hand had recently guided the Byrds’ “Mr. Tambourine Man” to the pole position in the US and UK; he was in the midst of massaging a small group of session players in an off-brand studio, including future International Submarine Band bassist Chris Ethridge and, as a favor to Kacey, a terribly green Ned Doheny. “I felt awkward and ill-informed. I guess in a way I was bluffing,” Doheny said. “I had no recording experience and no concept of tone. I just tried to comp the changes and stay out of the way.” Even though further detail concerning songs played and session players present has gone lost, Ned found his calling amid that misremembered 1966 session.

That fall, Doheny took his shaky grades and poised electric guitar to the University of California Santa Barbara, to fumble his way through a murky liberal arts program. Widow Bedgwick, Ned’s five-piece campus cover band, was formed around guitarist Paul Mondchine, goateed flautist Loren Kaplan, psychotropic drugs, and a forgotten bassist and drummer. Following freshman year finals, Ned’s brown eyes began to wander. His thumb outstretched on the 101, the privileged Doheny descendant hitchhiked 240 miles north to Monterey, to sit outside the County Fairgrounds performance space, listening in the mythical 1967 pop festival’s big acts. Though Terry Melcher sat on the festival’s board, Doheny balked at calling in a note. “I knew a bunch of people inside, but I was always loathe to ask for favors,” Ned said. “This has been a problem my entire career.” Later, Doheny left UCSB after a successful audition for Cal Arts in downtown LA. “I showed up with a Standel amplifier and a Mosrite guitar and walked out with a scholarship.”

He’d see no mortarboard ceremony at Cal Arts. “I was a terrible student,” Doheny later admitted. In lieu of diploma, Ned received a letter from the draft board, which caused a rift in his storied family, as the scion had all but made up his mind to dodge the duffle-bag drop, angering his father in the process. Estranged from his family, Ned took up residence on a floor owned by Book Bargain Center proprietor and Los Angeles Free Press merchant Karl Metzenberg. Known colloquially as “the Freep,” the left-leaning Free Press periodical was a touchstone for the Los Angeles underground, boasting a strong classified section, of which Ned Doheny was an infrequent skimmer. Ten months into Ned’s bedroll existence, Metzenberg pointed out an ad seeking an electric guitar player.

Savage Tales

Barry Friedman was one of a handful of producers working out of Elektra Records’ bustling west coast office, then located where Doheny Drive met Santa Monica Boulevard at Melrose. With important albums for Paul Butterfield, Kaleidoscope, and the Holy Modal Rounders visible in his rearview mirror, Friedman steered toward changing the fortunes of German-born 19-year-old Elektra staff writer Jackson Browne. Friedman auditioned Ned Doheny’s guitar “in some hotel room on Sunset Boulevard,” as Ned remembered. “I hooked up a little amplifier, played some Eric Clapton stuff, and was hired. Barry was looking for somebody to play with someone named Jackson Browne, who I thought must be some middle-aged blues man. Imagine my surprise when we met in Laurel Canyon and here was this scrawny Anglo kid who looked like a refugee from Boyle Heights.”

Thick as thieves in a matter of weeks, Browne and Doheny quickly found themselves sleeping on various floors off Laurel Canyon’s Ridpath Drive. In addition to Elektra’s producer core of Paul Rothchild, John Haeny, and Barry Friedman, the Ridpath route was familiar territory to the International Submarine Band, Tim Buckley, and Steve Noonan. So it was for Nico, out of the Velvet Underground and into LA just after her Chelsea Girl solo debut, its Browne-penned songs, and her romantic linkage to Jackson. For them all, Friedman’s mattress-strewn living room served as a sorting facility for exchanged ambitions and conquests. Amidst celebrity encounters and glittering orgies, music was being made. And this gave Friedman an idea. “The great thing about Barry is that, like all tricksters, he changed the world. Well, at least my world,” Doheny said. According to Elektra Records founder Jac Holzman, “He proposed a music ranch. Take talented kids out of the struggles of trying to make it in the city, give them fresh air, good food, and the freedom to create whatever music came to them.” Around Doheny there coalesced a cadre of box-spring refugees, including Jackson Browne, Rolf Kempf on piano and organ, Jack Wilce handling mandolin, banjo and guitar, and Peter Hodgson on bass. “Out of this symphony of self-indulgence and imaginary celebrity was born the Los Angeles Fantasy Orchestra,” Doheny said.

Friedman’s vision flew with Holzman and Elektra. He took a $50,000 budget in search of his ranch site, that mythic place beyond the canyons, first in the San Fernando Valley, then Marin County, before finally settling on Paxton Lodge, an abandoned resort deep in the Sierras, just north of Plumas National Forest and some 500 miles from LA. Recording equipment soon filled the dining room. Groupies doubled as maids and line cooks. Marijuana was trucked in by the kilo from redwood-rich Humboldt county. “It was the first time I had really been away from home,” Doheny remembered. “My parents probably pictured some sort of organized summer camp situation—shades of Spin & Marty. It was definitely a lot darker than that. We were babes in the woods. Most of us were decidedly out of our depth. Jackson and Rolf were a bit more seasoned, but even they fell under the spell of the place.”

That total lack of structure led to a country club atmosphere and, ultimately, an unfocused production. Drugs became an issue for some. Friedman spent most days holed up in his room with a needle in his arm. And while albums by Dave “Snaker” Ray and “Spider” John Koerner with Willie Murphy found their way into the can, the Browne/Doheny/Kempf/Wilce supergroup was floundering. Haeny was brought in to engineer, but—leaving aside a rhythm track featuring former Bob Dylan drummer Sandy Konikoff “ham-boning” with a microphone stationed in his rectum—precious little useable material ever materialized. “It was a pivotal experience for all concerned,” Ned recalled. “We weren’t going anywhere. We’d rehearse, we’d get high, we’d eat lunch, then rehearse some more, then eat dinner. But the songs weren’t getting written. The LA Fantasy Orchestra remained a fantasy.” Ned’s criticisms and candor ultimately led to his expulsion from the Feather River Valley.

The plug on Paxton Lodge was pulled in March of 1969, the unfinished remnants of Los Angeles Fantasy Orchestra’s unrealized album shelved and buried. “It was badly played and badly realized,” Jackson Browne admitted. “We named it ‘Baby Browning,’ after a stillborn child’s tombstone that we saw while we were walking around the local cemetery.”

“It was like asking a rat to leave a sinking ship,” Ned said of his dismissal from the Elektra Music Ranch. “I was pretty crestfallen about the whole thing.” Discouraged, he returned to Laurel Canyon and rented out the top floor of Elyse Weinberg’s duplex off Weepah Way. A Leyland Motors Land Rover appeared in the driveway on Ned’s 21st birthday, and strains on his familial relations began to relax. Through a connection at Cal Arts, Ned was invited to sit in with reedist Charles Lloyd, then living in Malibu and driving a Ferrari Berlinetta following the success of his twin 1966 breakthroughs Forest Flower and The Flowering. Ned joined a sometime-improvisational group that included bassist Kenny Jenkins, keyboardist Michael Cohen, and percussionist Jimmy Zitro; the quartet would ultimately back Lloyd on his Kapp-issued 1970 LP Moon Man. “These were literate jazzers,” Doheny said of his bandmates. “I was this more or less self-taught person adding tone to a somewhat crowded field.” A discrepancy over remuneration ultimately forced his adjournment, the second time in a year that Ned’s opinion had cost him a gig.

Young, handsome, single, and with a name that still carried a certain amount of gravitas, Ned Doheny immersed himself in the culture of Los Angeles. His neighborhood saw a second wave of settlers, including Graham Nash, J. D. Souther, Glenn Frey, and Carole King. Despite the Paxton ordeal, Jackson Browne remained a close friend. “I watched him write his first album that winter,” Doheny said. Though his electric guitar gun was hired frequently for engagements at the Troubadour, Doheny’s musical story arc had plateaued. Westwood Music’s Fred Walecki passed along the digits for British-born guitar deity Frederick Noad, whose influence would alter Ned’s approach to the instrument permanently. “Frederick Noad was the first truly transformational student-teacher relationship I ever had,” Doheny said. “Fred was as important to my first album as anyone who played on it.”

Whereas the Ned Doheny of the 1960s was little more than a serviceable bonfire sideman, he confronted the Me Decade imbued with a new set of skills. “Frederick Noad basically set my hands free,” said Doheny. “The year of classical guitar changed everything. It gave me a sense of economy that I never had before. And made my hands really strong.” His translucent acrylic Ampeg Dan Armstrong was traded in for a handcrafted Manuel De La Chica nylon string acoustic. “I got to a point where I had all this information and all this dexterity, but I’d yet to write a song I was convinced by,” Ned said. “The words came with much difficulty for me. I don’t consider myself a poet. There are some people who are born with that gift, but I never believed I was one of them.”

Doheny’s earliest composition fell right into line for a man who’d describe himself more than once as an “avatar for casual vulgarity.” “The first song I wrote was ‘On And On,’” Ned remembered. “There’s actually a version that Jackson had written lyrics to. One of his lyrics was ‘Searching for the opening to another paradise.’ And just before we went on stage at the Troubador, I said, ‘Was that “Searching for the opening to another pair of thighs?”’ After we pulled ourselves together, the song was pretty much shot for him.”

Stalled out in Los Angeles, Doheny made his first bold move in 22 years. “I was going to drive around the world,” he laughed. Packing his Land Rover to the roof with an amplifier, a Fender Telecaster, a Roy Noble custom acoustic, a palm mattress, a suitcase, and a few coats, Ned lit out on Route 66, hung a right at Chicago, and then barreled on toward New York City. A line of credit was established and a room secured at The Pierre, with a balcony overlooking Central Park. He spent three days walking around the city in a Cherimoya Indian-style jacket before loading the Rover onto the QE2 and setting his bearings for England. “I’ll drive around Europe, find out what the music scene is about,” Ned thought. He made the Atlantic transit safely enough, but he never did cross the English Channel to the mainland.

Canyon rumors of Ned’s departure traveled faster than the QE2’s 32 knots per hour, and when Ned arrived in Southampton four days later, a corps of old acquaintances awaited him on King’s Road in London. Nicole Tacot, daughter to Traffic manager Charles Tacot, had been a fixture in the Hollywood Hills since her teens, and would be Doheny’s chaperon during his time abroad. Soon, Ned found himself in the English countryside, on a floor owned by former Traffic guitarist Dave Mason, picking through the recently finished “On And On.” Just hours later, Doheny’s “Trust Me” was complete, and Mason was formulating a plan. When Cass Elliot turned up a few days later, in the midst of a UK press junket, the Mason, Cass & Doheny trio was born. “The first time we sang together around Cass’s kitchen table our vocal blend was really quite amazing,” Ned remembered. “I left my Land Rover in Britain and came home in a limo.” He’d been gone only three weeks.

On paper, the troika read like a very safe bet. Mason was coming off a career high in 1970’s Alone Together; Elliot had recently departed the Mamas and the Papas and was in the bosom of a successful solo career; Doheny was the dreamy oil-dynasty heir with emerging chops. Traffic’s management team of Charles Tacot and Billy Doyle were brought in to handle the trio’s day-to-day. Prior to a single note’s recording, fashion photographer Clive Arrowsmith was hired to snap off a few rolls of medium format. A wing at the Chateau Marmont was charged to somebody’s credit card. And yet all was not well. “All groups, no matter how well established, are always on the verge of breaking up,” Ned said. Before they could even take the Troubadour stage on a Tuesday night, Mason, Cass & Doheny parted ways as friends. Doheny’s “On And On” would take the lieutenant position on 1971’s self-titled Dave Mason & Cass Elliot LP, continuing a byline trend that would carry him through most of the decade. He retreated back into the canyons that spring, taking a home with a pool at 2515 Benedict Canyon Drive. There, Ned Doheny would write and rehearse much of his own self-titled debut LP. All he needed now was a record deal.

Labor Of Love

They’d meet at Dan Tana’s and the neighboring Troubadour, or Lucy’s El Adobe Café, then go anywhere the night took them. Jackson Browne, J.D. Souther, Glenn Frey, Ned Doheny—men who, in 1971, were regarded by very few as important artists. Souther and Frey were rebounding from the demise of their long-running folk-rock duo Longbranch Pennywhistle; Browne, downstairs neighbor to Souther and Frey, was still smarting after Elektra dropped him two years prior. All four were in search of a record deal; that their upcoming LPs all ended up sporting the same logo was hardly coincidence.

Asylum Records had been born of co-founder David Geffen’s fascination with Jackson Browne. Unable to secure a contract for the mustachioed soft-rock pioneer, Geffen struck a deal with Atlantic Records to bankroll his fantasy label. All of Asylum’s artists were locked into contracts at management concern Geffen-Roberts across the hall, with publishing rights tied up in Geffen’s Benchmark Music venture, insuring that Geffen controlled not only two sides of every nickel, but each coin’s edge as well. Browne would prove to be Geffen’s conduit to signing Laurel Canyon’s less likely denizens, as Asylum/Geffen-Roberts/Benchmark would, in short order, ink contracts with newly formed Glenn Frey/Don Henley act the Eagles, plus solo deals with Souther and Doheny. None of them thought more than once about Asylum’s label image: a forbidding wooden madhouse door set adrift on a calmly clouded sky. “When I looked at the contract David handed me at Asylum, he was miffed that I wanted to read it. Miffed!” Doheny recalled. “He said, ‘What’s the matter? Don’t you trust me?’ I should have known better.”

Even so, Doheny put his confidence where Browne’s had been, signing the dotted line for Geffen’s trio of companies on June 1, 1971. With that, he began putting pieces of his debut album in place. For a backing band, Doheny stripped spare parts from two rather minor major label acts: Warner Brothers’ Things To Come and Columbia’s Raven. Things bassist Bryan Garofalo had come to Ned’s attention at Cass Elliot’s pad on Lookout Mountain, while Raven keyboardist Jimmy Caleri and drummer Gary Mallaber were sourced from the margins of the Troubadour scene. In a pool house on Benedict Canyon Drive, the quartet spent months working out arrangements for “On And On,” “Trust Me,” “Fineline,” “I Know Sorrow,” “Lashambeaux,” “I Can Dream,” “Postcards From Hollywood,” “Take Me Faraway,” “It Calls For You,” and “Standfast.” “Those first ten songs on the first record were the first ten songs period,” Ned said.

But not all of Doheny’s early career work was work as it’s typically understood. Through Metzenberg, confirmed non-actors and relative longhairs Browne and Doheny were cast as languid steamroom stoners in Bruce Clark’s coarsely countercultural 1971 film The Ski Bum, set in a richies-vs.-hippies vision of Aspen, Colorado, and featuring music by Joseph Byrd, fresh out of Los Angeles avant-psych outfit the United States of America. Back on LA’s slopes, 2515 Benedict Canyon hosted its share of flesh displays and Scrabble tournaments, peopled by Hollywood’s rogue class of actors, musicians, and groupies. Shortly after signing with Asylum, Doheny, Browne, Souther, Frey, and Henley headed east into sun-scorched Joshua Tree, indulging in a post-Morrison, peyote-sponsored spiritual journey. “In those days, we were all really good friends,” said Doheny. “We spent that time in the desert together howling at the moon. In those days we were family.”

Doheny began production on his debut LP in the summer of 1972 at Sunset Sound in Hollywood. Paxton survivor John Haeny was hired to engineer and produce the four-week session. Graham Nash’s work on backing vocals initially left Ned in want of additional harmonies, for “I Can Dream,” “Fineline,” and “On And On.” He tapped Frey and Henley, because, as he modestly put it, “They were the best harmony singers I knew.” Even so, Nash’s rendering of “I Can Dream” was selected for the final product, alongside Eagle-free versions of “Fineline” and “On And On.” Separate Oceans presents all three songs with Frey/Henley vocals intact, though Ned remains unequivocal about Haeny’s role in the sessions. “John was the voice in the control room. He made recommendations about takes and tone so that we could go on about our business without having to run back and forth constantly,” Ned said. “I stood behind the songs. To us, it sounded like something new and exciting and we all thought it would make us famous.” When time came to mix the tracks, Doheny got unsettling news: Asylum couldn’t afford to finish the album. “They spent an awful lot of money on Jackson, and by the time it was my turn to do all that stuff, the tanks had been emptied somewhat. And I just coughed up the dough because I wanted to see it finished.” In an instant, $25,000 vanished from Ned’s trust fund and the goodwill account he held in David Geffen took a serious hit.

Excepting only self-titled records by Angelenos Jo Jo Gunne and Las Vegas duo Batdorf & Rodney, the first nine Asylum LPs assembled a formidable roster of Canyon denizens. Judee Sill made her folky debut with SD 5050; David Blue’s fourth LP got 5052. As SD 5057, Joni Mitchell’s For The Roses caught both the songbird’s jazz-influenced transition and the Top 40 with “You Turn Me On I’m A Radio.” And on Byrds, SD 5058, Roger McGuinn and the original Byrds lineup took wing one last time. But Geffen and his inmates arrived at Ned Doheny, SD 5059, in June of 1973 with the typical ratio of hits to misses. The Eagles and Jackson Browne, Asylum’s only hot properties, got the label’s most generous financial stoking by a wide margin. As a white-labeled promo featuring stereo and mono cuts, Doheny’s “On And On” made its way to radio stations, but no serious effort to push it up—or even onto—the charts was ever made. It got no advertising in print, although a lone review did appear, in the July 19, 1973, issue of Rolling Stone:

“Here is a debut album that is all of a piece, a sort of Southern California Astral Weeks, its material supremely laidback, acoustical jazz-rock that on first listening is pleasant, and after several more absorbing. Doheny possesses a high, almost frail tenor that is somewhat reminiscent of a Todd Rundgren without the hysteria. He phrases like a cool jazz man, seldom using his voice other than as the leading line above a tightly-coordinated instrumental texture. Though this approach de-emphasizes Doheny’s wistfully appealing song lyrics to the point that they hardly count at all, it increases one’s awareness of Doheny as a musical thinker of exceptional sophistication. Among the better-known contemporary singer/songwriters, only James Taylor shows a similar tendency toward such aristocratic reserve, but Doheny carries this reserve much farther. The final impression Doheny leaves behind is one of prodigious musical intelligence combined with an attitude of serene resignation. It makes for a subtly intoxicating brew—good rainy day/Sunday afternoon listening.”

Asylum dumped a good deal of its support effort for Ned Doheny into a 5’ X 5’ paint-by-numbers recreation of Henry Diltz’s album cover shot, affixed to a streetside pole at Tower Records’ Sunset Boulevard outpost. “Some people got billboards, I got a postage stamp,” Ned joked. As de facto in-house photographer for Asylum, Diltz exposed several rolls of a relaxed Ned outside a frescoed stucco San Clemente hotel courtyard, sporting a white canvas Nudie Cohen duster. “I had the mentality of these musicians,” Diltz recalled. “We were brothers. We were all just guys hanging out. We’d just take a trip somewhere. We’d take hundreds and hundreds of photos and then have a slide show and the good ones would stick out.” Cropping the chosen image to fit the album’s 12”-square jacket permanently excised the Diltz shot’s defining element, a small placard reading: “Please Ring Bell For Office.” In any case, few came a-calling for Doheny’s initial offering, and the front-door-facing street ad brought too few buyers of Ned Doheny to Tower Records cashiers. SD5059 was D.O.A.

On the topic of Asylum, as David Geffen had colorfully put it, “I’ll never have more artists than I can fit in this sauna.” But as Joni Mitchell, the Byrds, Tom Waits, and Linda Ronstadt filed into the hotroom, Ned Doheny was finding himself elbowed out. “David was looking elsewhere,” Ned posited. “And once the music business lost its allure, he cashed out and moved on. The rest is history. Perhaps I could’ve stayed with Asylum, but at that point it had begun to resemble Paxton,” Doheny reflected. “I’d kind of become the whistleblower. One night at Tana’s, I was sitting with Don [Henley], and Glenn [Frey], and [veteran agent] John Hartmann and I said, ‘Doesn’t it strike anybody as unusual that our management and our record company are one and the same?’” Word of Ned’s critique wound its way through the Canyon and into Asylum offices at Doheny & Sunset. Ned opted out of his management and recording contract soon after. “David didn’t really understand my music,” Ned said. “I couldn’t be bought. I came from a wealthy family. He couldn’t rescue me, I’d already been saved.”

Even with his namesake dynasty in decline, Ned remained a fortunate son of Los Angeles. “We were bedazzled,” Ned recalled of this period. “You’re with this actress and that producer and you begin to lose touch. Suddenly you’ve become that same grinding-out-your-cigar-on-the-outstretched-palms-of-the-poor cynic that you fought so hard not to become in the beginning.” Doheny had a fellow cigar-grinder in influential early-FM pioneer Richard “Clam Balls” Kimball, then program directing at Los Angeles’ eclectic FM outlet KMET. Kimball had no management pedigree, though he enjoyed connections with the various single pluggers and A&R men who routinely walked through KMET’s door with a handful of bills or a bag of dope. “One night at Tana’s, Ned said to me, ‘Why don’t you manage me?’ FM was getting a bit corporate, and I was getting a bit bored, so I said yes,” Kimball remembered. He quit KMET in the fall of 1974, signing on for the adventure that would consume his next four years.

Exploiting The Blues

While Ned’s Laurel Canyon brethren were busy takin’ it easy on the road to the Hotel California, bearded Dundee, Scotland, natives Average White Band turned up in Los Angeles in the fall of ‘74, repping their Atlantic-issued sophomore LP AWB. “We had all gone to the Troubadour and were absolutely stunned by how well these guys played and sang,” Ned said. “Some heavy duty personalities came down to see them, too. They were a unit, clearly.” Where 1973’s Show Your Hand had the sextet exploring the edges of Clapton’s white boy blues, AWB moved the group toward the blue-eyed soul camp. The record shot to #1 in short order, powered by “Picking Up The Pieces,” building the Anglo-soul movement a fire to warm itself around. Ned Doheny took immediately to pounding stakes of his own at the site.

On September 23, 1974, a dose of strychnine-laced-heroin took the life of AWB drummer Robbie McIntosh at a Los Angeles party, setting off a series of events that impinged on Ned Doheny’s course. Average White guitarist Hamish Stuart became a Dan Tana’s mainstay in the days and weeks following his best friend’s demise; Stuart also started up a relationship with an ex-girlfriend of Ned’s. ”When he and I were introduced, he had nodes on his vocal chords, so he had to write things down,” Ned reported. “I sort of took up a little of the space that was left by Robbie’s passing. When [Stuart] finally started to feel a bit more comfortable, we went up to the house and started fiddling around.” Out of that fiddling came “A Love Of Your Own,” a song that would define the next few years of Doheny’s life. “We just came up with it on the spot,” Ned continued. “It was about an hour and a half’s worth of noodling. Hamish wrote the bridge, and I wrote most of the melody for the verses. We were shocked at how quickly it came. The song worked, especially as an octave vocal, it was traditional without being traditional.” A few days later, a ragtag group of past and present Doheny compatriots crammed into a ramshackle studio at the bottom of the hill to demo the new song. What was left of Doheny and Stuart’s post-pubescent falsettos led an in-unison attack, with Ned wielding the up-ticked acoustic in time with Hamish’s diamonds-in-the-back bass line. AWB’s Roger Ball provided the keystroke washes, and former Raven lead guitarist Ernie Corallo added chorus-y flourishes. Session rhythmist Gary Mallaber set the ballad’s pace. Left un-run was the race to get the song on an album. Hitmakers already, Average White Band had the inside track. But Ned Doheny wasn’t too far behind.

Following Benchmark Music’s sale to Warner Communications, Doheny compositions were being flogged by a series of song pluggers. Warner’s Artie Wayne was assigned to Ned’s case in 1974. When the “A Love Of Your Own” demo hit his desk, Wayne had already sold a spectrum of performers on Ned’s versatile “Get It Up For Love.” It got a lush acoustic guitar lead from broken-winged Partridge ex-pat David Cassidy, distinctive electric guitar klaxons from rock stalwart Johnny Rivers, studio bombast and a Kim Carnes vocal from Troubadour also-ran Stephen Michael Schwartz, a socially motivating rewrite from the Fabulous Rhinestones, and blood, sweat, tears, and horns from Chicago latin-funk no-namers The Mob. On the suggestive song’s upbringing, Ned said, “The first time I played ‘Get It Up For Love’ was at the Troubador. David Geffen was in the audience, and as soon I got to the chorus, his head whipped around. I suspect he thought my choice of words showed a want of good taste. And most of my brethren at Asylum probably thought it was a cheap shot.” But for Doheny, the entredre was at least double. “I was talking about summoning your resources and getting your shit together. You could just as easily say ‘Get it up for life’ but you’d sound like a moron. ‘Get it up for love’ makes it a little more…seminal.” The song would also end up playing a crucial role in Ned’s next project.

Lorne Saifer, a Winnipeg-born A&R man, had come to the Columbia Records fold following the 1975 dissolution of The Guess Who, a band he’d managed. Why Saifer defected from Canadian boogie rock to LA’s lax marina set is anyone’s guess, but Saifer’s interest in Doheny led Ned’s pen to Columbia paper in that same year. With Kimball handling business affairs, Ned Doheny took on responsibility for just one thing: writing the Columbia-branded follow-up to Ned Doheny. Early on, “On The Swingshift” and “If You Should Fall” emerged from similar territory. “The idea of a swing shift was sort of an old school reference—it’s the shift between three and midnight,” Doheny said. “That was kind of what was going on every night down at the Troubadour. Hangin’ and waiting for something to pop. You’d sleep ‘til late and then you’d have breakfast and then you would smoke lots of weed and play until your hands hurt, then go out, eat late, and come back sometimes with people who also played, then smoke more weed, and then you would play...” As for “If You Should Fall,” which rode shotgun on Ned’s second album, there was “just the whole idea of kind of having a strange job. To go down and cast your net.” Those two—plus the pre-booty-call wink of “I’ve Got Your Number” and the can’t-get-her-when-I-want-her/don’t-want-her-when-I-have-her ballad “When Love Hangs In The Balance”—were demoed under the watchful eye of former Elektra producer Paul Rothchild. With five tracks dressed and ready, half an album spiraled at the hoop’s edge. Steve Cropper leapt up for the tip-in.

His ear had presumably been turned by a Wayne-distributed tape of Doheny/Stuart’s “A Love Of Your Own.” Cropper, a guitarist pillar since 1961 within Stax house band The MGs, had spent the preceding five years architecting albums for a string of first-balcony major label acts (including Jeff Beck, Jose Feliciano, and Cold Blood) plus a few from the industry’s nosebleeds (among them Roy Head, Ronnie Stoots, and Diane Kolby). Doheny came to Cropper as yet another also-ran. The Cropper-produced Hard Candy sessions commenced in the fall of 1975 at Clover Studios at Santa Monica & Vine with former Stevie Wonder knob twiddler Austin Godsey behind the board. Ned supplied his usual suspects—drummer Gary Mallaber, guitarist Ernie Carello, bassist Brian Garofalo—alongside Asylum alums Henley, Frey, Souther, and Linda Ronstadt. AOR keyboard specialist David Foster stepped in to smooth out what was left of Ned’s Canyon creases. For finishing touches of brass, Cropper looked a few hundred miles north to Oakland and the additional soul wattage of Tower of Power’s Emilio Castillo, Stephen Kupka, Greg Adams, Mic Gillette, and Lenny Pickett.

As for Hard Candy’s imagery, Henry Diltz’s road-trip photo shoot concept stuck with Doheny. In ’73, the two of them had traveled to Baja California to expend promotional funds and silver halide for Ned on the beach, Ned with feathered hair, and Ned pummeled by crashing waves. Shy of Diltz invoices and his methods, Columbia called on Moshe Brakha, whose work on Boz Scaggs’ breakthrough album Silk Degrees graced shelves in March of ’76. A shoestring expedition returned Doheny to the southern tip of Baja and San Jose Del Cabo’s Hotel Palmilla. On capturing the sleeve’s Ned-drenching snapshots, Brakha said: “This was during a period where you didn’t even get to take an assistant. I asked one of the waiters to splash water on him.” With its publicity allowance blown on Mexican hotel rooms, Hard Candy was released in bulk by Columbia in June. Scaggs’ “Lowdown” had filled Columbia’s white-soul smash quota, with next year’s coinage earmarked for upcoming Walter Egan singles. When neither Ned’s “A Love Of Your Own” nor “If You Should Fall” caught ears on the radio, Hard Candy dissolved in a saltwater sea of easy gliders.

Two years shy of his 30th birthday, and saddled with a pair of unsuccessful LPs, Ned Doheny stayed in surprisingly good spirits. At Nate n’ Al of Beverly Hills Delicatessen, he met 21-year-old LA scene queen Cynthia Bousquet, with whom he soon got cozy in a new house on Castilian Drive, just over the ridge from the Hollywood Bowl. Despite the drying bits of egg on Lorne Saifer’s chin and cheek, he agreed to finance a short promotional Doheny tour, to kickstart his floundering signee. Dates in Portland and Seattle were booked, and backing musicians signed in drummer Mallaber, bassist Dennis Parker, and keyboardist Joey Carbone. But Ned—smitten with his new love—insisted that Bousquet accompany him on tour, ushering in stresses both financial and otherwise. “She was very time consuming,” as Richard Kimball charitably put it. Distracted and unfocused, Ned watched his gigs dry up and his career pulse along on life-support.

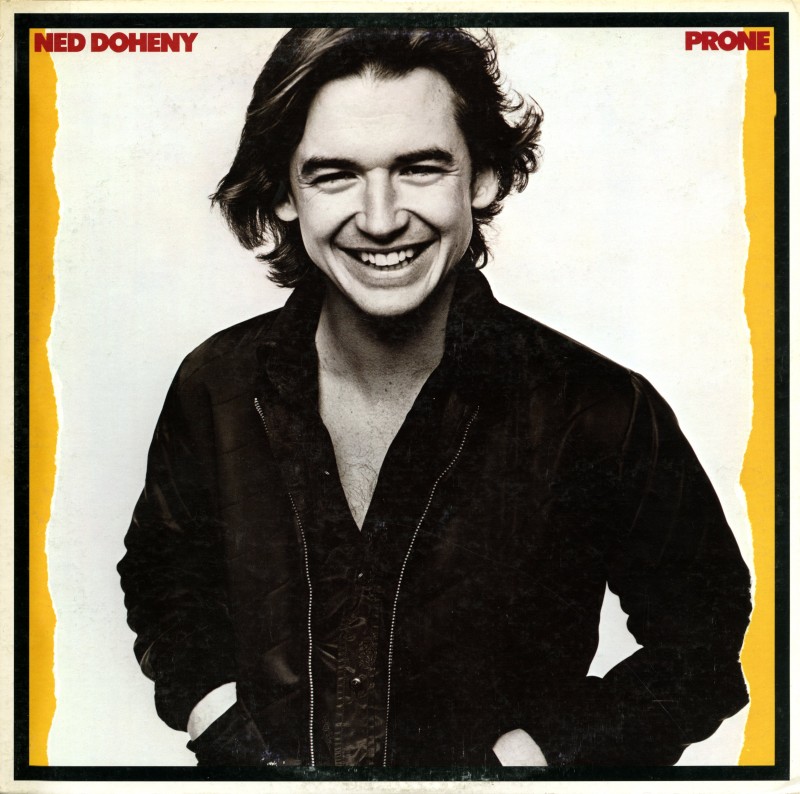

Still, Saifer convinced Columbia to foot the bill for another Ned Doheny album. “It was too soon,” Ned said of sessions for Prone, which commenced only a few months after Hard Candy’s unwrapping. With Cropper returning to the helm, Doheny marched back to Clover at the end of 1976 to record what would be his last album of new material for twelve years. The bare bones of eight songs came in under Ned’s arm, the oldest of which, “Devil In You,” was an unfinished holdover from his days on Benedict Canyon Drive. He poured an overflow of Bousquet obsession into song, as “Guess Who’s Lookin’ For Love Again” mused on a break-up’s aftermath (“Sometimes you feel like a souvenir”). The ninth piece of the Prone puzzle began as a Mallaber/Doheny two-step lark, before Cropper heard disco’s siren in the distance and coaxed “To Prove My Love” out of its wallflower shell. The old gang was back on board, including Mallaber, Corallo, Parker, Souther, Carbone, and Foster (plus Steve Perry and Jeff Porcaro, prior to both Journey and Toto) with the Wrecking Crew’s Lew McCreary, Jim Horn, and Quitman Dennis taking the place of Tower Of Power, and a pre-Sweet Forgiveness Bonnie Raitt adding her mezzo-soprano on “To Prove My Love,” the album’s eventual opener.

But as America’s bicentennial faded into memory, Prone slipped lower and lower on Columbia’s priority list. Saifer’s efforts went into launching the Portrait subsidiary label, leaving Ned few cheerleaders within Columbia ranks. “I remember [Columbia exec] Don Ellis called us into his office,” Richard Kimball recalled. “We knew our days were numbered. Don was teary-eyed when he told us they were dropping Ned.” The label cut Prone from its release schedule as well. Just before Christmas, Cynthia moved out. And ’77 only got worse. Karl Metzenberg, one of Ned’s oldest friends, was hit head-on at the wheel of his VW Bus, by a driver in search of a cassette tape under her seat. Karl’s left leg came off at the knee. Returning a decade-old favor, Ned opened the door to his now-empty single-story for Karl’s recovery. The rollicking yesteryear nights of Tana’s, the Troub, and THC were replaced by an endless series of chain-smoked Camels and bedpan changes performed by Ned in service of Metzenberg. The kidney-shaped pool went unused; Kimball was relieved of management duties. When a cover of “A Love Of You Own” made Melissa Manchester’s sixth LP, the resulting royalty pennies gathered at the doorstep, as celebrated as a sack of threadbare Salvation Army button-downs. Just as Edward Doheny had shut out the world following the very public Teapot Dome scandal and his son’s subsequent murder-suicide, Ned drew the shades on his Hollywood Hills home and retreated inward. “I had to sleep with all my windows open,” Ned said. “It felt like the roof was coming down to meet me.”

Tricky Situation

Unbeknownst to Ned Doheny, and in spite of near-universal American disinterest, both his debut LP and Hard Candy had made inroads into lands across both Pacific and Atlantic oceans. In London, an instrumental “To Prove My Love” mixed for TV broadcast had leaked into clubland and became something of a dance hit. The CBS label rushed a 12” single to market, with Hard Candy's shuffley “On The Swingshift” tacked onto the flip. Nine time zones away from there, a Japanese fanbase offered no domestic Doheny pressings had elevated his pair of albums to collector status, via dubs distributed from fan to fan. During three months of unprecedented LA rain in the dolorous spring of 1978, a promoter in Japan rung Ned up, to test his interest in flying over for a few gigs. According to Ned, “I had nothing better going on, so I thought, ‘What the hell?’” His autumn arrival in Tokyo was thronged by a flock of reporters and a rash of interviews. “I’d never experienced that kind of crush,” Ned said. Backing him on the brisk three-date tour were keyboardist David Garland, bassist Colin Cameron, drummer Richie Pidanick, longtime side guitarist Ernie Carello, and a plethora of air-guitaring fans. “After the show in Osaka, we get back to the hotel and there’s a crowd of people, a couple hundred maybe, and we were thinking there must be some kind of Japanese luminary staying there as well,” Doheny said. “I stepped out of the van and was immediately mobbed. I was saved by the doorman. He’d obviously done this sort of thing before.” Following a final date in Fukuoka, Ned and cohort boarded a plane headed back homeward, intoxicated by their newfound celebrity in the Land of the Rising Sun. He awoke mid-flight to a blanket spread lovingly over him...by a stewardess who’d just seen him live at Osaka.

In the following year, Sony—working as CBS’s Japanese distribution partner—issued Prone, Ned Doheny’s shelved third album. The front and back covers featured monochrome snaps by Life magazine photographer Gary Heery, capturing a grinning Ned in a quilted silk jacket. Of the one-word title, Ned remains mostly mum: “I can’t say that I cogitated much on it.” The Japanese market did the exact opposite, hanging on its every word, or in the case of “To Prove My Love,” its wordlessness. When Prone came to market, only the oohs, heys, dit-dit-dits, and titular lyrics of the lead track remained. It would be more than a decade before the vocal version surfaced, on Prone’s 1991 compact disc edition—for Japan only, of course.

Stateside, the Doheny surname still oriented LA motorists, while exerting far less street influence over the coming decade. Maxine Nightingale and Tata Vega’s covers of “Get It Up For Love” would be Ned’s last bylines of the 1970s. He was writing less, though a handful of visits from his old pal Hamish Stuart and a few plinks on the Castilian house’s Steinway awoke the beast for one last run at the charts. “He had no urgency to finish anything,” Stuart recalled of Doheny adrift. “We were looking for songs. And Ned and I got together to try and write again, but it just wasn’t coming....I started to play the first sequence of chords and Ned jumped in with that first line. It took us four or five sessions to finish ‘What Cha’ Gonna Do For Me,’ because Ned tends to live with songs for a really long time before he cuts them.” Stuart’s Average White Band took its first stab at the song with David Foster at the helm, convening at Sunset Sound as 1979 waned. Habitual AWB producer Arif Mardin happened to be in the studio for the session, with Chaka Khan, his latest project, in tow. “I was in the booth doing a little scratch vocal, and there in the control room is Chaka Khan,” Ned said. “The next thing I know, her face is peeking around the door and she’s asking, ‘Do you mind if I sing with you?’” AWB got their version of “What Cha’ Gonna Do For Me” into the marketplace first, as Track 4, Side A, of their forgettable Shine LP in March of 1980. But what Chaka did with “What Cha’ Gonna Do For Me”—slotting it second on an LP named for the cut—propelled it to the top spot on Billboard’s R&B chart in May, 1981. Call it the first and last hit of Ned Doheny’s career.

And sure enough, Doheny returned to the studio early in 1982 to cut his own version of “What Cha’,” plus three more originals: “Before I Thrill Again,” “Life After Romance,” and “Love’s A Heartache.” The Record Plant session was commandeered by former Rufus and Chaka drummer Andre Fisher, who had produced Vega’s “Get It Up” cut a few years prior. Cuban percussionist Luis Conte lent signature talking drum to “Love’s A Heartache,” while Yellowjacket jazzbos Russell Ferrante and Jimmy Haslip handled keys and bass, respectively. In-demand session drummer John “J.R.” Robinson kept time, fresh off laying down thriller rhythms for Michael Jackson. Cassette dubs of the Record Plant work would percolate out to song pluggers, producers, managers, and artists, resulting in translations of “Love’s A Heartache” by Average White Band, Leslie Smith, and Kasu Matsui, for fusion-rabid Tokyo audiences. But the Nikkei index would near its historic late-’80s pinnacle before a new record deal materialized for Ned.

During a six-year absence, Ned busied himself with marrying and with siring an heir to the dwindling Doheny fortune. In Japan, his popularity only continued to grow. Nearly ten years down the line from his brief and eye-opening sojourn to the far east, Doheny signed a recording contract tendered by Japan’s Polystar, which issued his next four albums: 1988’s Life After Romance, 1991’s Love Like Ours, and 1993’s Between Two Worlds. Postcards From Hollywood, Doheny’s pre-recorded radio program, aired between April 1990 and September 1993 on FM Yokohama, spawning an acoustic 1991 Polystar album of the same name. This work and his handful of tours permanently cemented his status as “Big In Japan.”

On June 22, 1993, Lucy Doheny Battson, Ned’s paternal grandmother and oldest living connection to the great Doheny fortune, died of natural causes. “We were always reticent to publicize our circumstances out of deference to my grandmother,” Ned said on behalf of Lucy’s 14 grandchildren, 27 great-grandchildren, and two great-great-grandchildren. While none of those offspring collected mightily on their familial connections to fossil carbon, a few left notable footprints through the wilds of the creative arts. Dennis Doheny became a highly regarded landscape painter; Larry Niven, cousin to Ned Doheny, has long been a respected author of book-length hard sci-fi. Born a financially assured scion, Ned Doheny polished his art at his own leisured pace, spoke up when fantasy orchestras floundered, dared to eschew the attentions of no less a force than David Geffen. From at least that vantage point, Ned’s career in music reveals itself as a controlled series of experiments, in which failure in the eyes of a churning recording industry loomed less as a threat than as an acceptable risk. Still, acceptance by the machine remained a longed-for goal: “Sometimes, no matter how hard you pound on the door it won’t open,” Doheny said. “And it doesn’t matter which hand you use. It’s almost as if you have to lose yourself in the rush of days and let things simmer before you become relevant. If it happens at all.”

Ken Shipley, January 2014