At the end of the Future of What tour, in May 1995, each member of Unwound went home with a $1,500 profit share. The deal Unwound signed with BMG a mere three months later, by comparison, was a mid-five-figure windfall. It granted BMG 50% of the publishing rights for the follow-up to The Future of What, with options on two subsequent albums beyond that—each of which, if picked up, could earn the band an additional sum in the low-to-mid five figures, depending on sales.

On the BMG side, there were two angles at play. For Margaret Mittleman there was an element of altruism. “Not only did I really love the music, I thought they were great people,” she explained. A few months after the signing, she even jumped in the van with Unwound for a few shows.

For her bosses at BMG, the signing was a low-risk bet on Unwound’s commercial potential. But even if Unwound failed to hit, simply having their name on the BMG roster could pay off as a chess move. “The investment was low compared to the outcome if you were to, say, attract the next Beck or Elliott Smith,” Mittleman explained. “It’s a magnet. I mean, that’s not what I was intending to do, but if they [BMG] were thinking it—and they were thinking it—I was fine with that.”

Of the money Unwound received, 10 percent went to Kill Rock Stars. Another chunk went toward the purchase of a new van and equipment. The remainder was divided equally between Justin, Vern, and Sara. “At that point, from late ‘95 to ‘97, ‘98, we were just doing the band,” Justin said. “I don’t think anybody had jobs.”

But the publishing money wouldn’t last forever. And when it finally dried up, Justin said, “That was crisis time.”

By early November, Unwound were back in Los Angeles for the kickoff of a quick two-week jaunt through the south and southwest. Half the time, they’d once again be opening for Fugazi, in conjunction with New York band Blonde Redhead. The other half, they’d be supporting Sonic Youth, alongside the Chapel Hill quartet Polvo.

For any up-and-coming band in 1995, the chance to open for either Fugazi or Sonic Youth even once was coveted. Being selected to tour with both, back-to-back, was a major coup. Factor in the new van, the new equipment, the money in their pockets, and it’s safe to say that Unwound were having an extremely good year.

The night before the first show with Fugazi—a mammoth event at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles that drew approximately 4,000 people—Unwound and Blonde Redhead shared a bill at Jabberjaw. It was their first meeting, and in terms of their musical backgrounds, the two bands could not have been more different. Simone and Amedeo Pace, Blonde Redhead’s drummer and lead guitarist, were trained jazz musicians from the Berklee School of Music; Kazu Makino, the band’s vocalist and rhythm guitarist, was a classically trained pianist. The members of Blonde Redhead were also far more worldly: Makino had been raised in Kyoto, the Pace twins in Milan and Montreal.

“I think it was an other-side-of-the-tracks thing,” Justin said. “They’d always be befuddled by some of our behavior. They’d ask us, ‘Is that what people in Olympia do? Is that what Olympia people are like?’”

“They were pro,” Vern recalled. “Seriously, who the fuck gets up at 6 AM to jump rope and eat breakfast out of a rice cooker they had in their van? I didn’t get it; nobody did. We were polar opposites, but the same world.”

“The northwest to me was a really faraway place and just sounded very exotic,” Makino explained. “We weren’t even living in New York very long, so we were discovering what American people were like, basically. And [Unwound] were like the first dog we saw as a puppy, they forever became the coolest animal.”

Most of all, Blonde Redhead were astonished by “the impact of the music,” Makino said. “I think we had huge question marks coming out of our heads as we watched. It almost sounded like classical music to me, what they were playing, because I couldn’t tell how each person, how what they were playing related to one another. I remember asking the twins, do you get this? It sounds beautiful, but do you even understand it? And they were like, no, not really.”

We were polar opposites, but the same world.

They only played a half-dozen shows together that November, but Unwound and Blonde Redhead would cross paths again and again over the next several years, both as tourmates and friends. In the fall of 1996, Blonde Redhead would even recruit Vern to play bass on their third album, Fake Can Be Just as Good, which they recorded in Seattle with one of Unwound’s studio engineers, John Goodmanson.

The story at the time was that Blonde Redhead brought Vern in because they “didn’t have a bass player,” Makino said. But also, she admitted with a laugh, “we just wanted to make a record that remotely sounded like Unwound. And that’s what we did.”

Unwound didn’t start traveling with a rice cooker, but through immersion, the tour practices of bands like Blonde Redhead, Fugazi, and Sonic Youth were slowly absorbed. “Financially we were taking cues, especially,” Sara said. “At first the band paid for everything. Justin found a guitar he wanted, the band paid for that. The band paid for those dudes’ cartons of cigarettes. Every meal, the band paid for. Then we learned about per diems, and we had to make decisions like, okay, if we’re getting PDs, does the band pay for every meal? And then eventually being like, no, the band doesn’t pay for anything, we just get PDs and it’s up to you how you spend it.”

Fugazi and Sonic Youth were two different operations. Fugazi traveled in a minivan and a U-Haul, with no more than a roadie and a sound engineer as crew. Sonic Youth had two separate tour buses, one for the band and one for an extensive crew, along with a semi-trailer full of gear. “But I think one thing we got from both of those bands—in probably equal degrees—is, this is how pro-bands act,” Justin said. “There was a level of efficiency that we picked up on. We started taking some of the logistical elements a little more seriously, just stuff like being on time, getting in a soundcheck.”

Incrementally, Unwound seemed to be winning people over. “Consistently throughout our life as a band, we had the experience of playing to a room of blank faces,” Sara reflected. “But I think Sonic Youth’s crowd was more open to seeing this band they’d never heard of. People would stand there barely reacting, and then when we were done people were totally gushing at us.” “It’s funny because as much as we looked up to Fugazi, in certain ways we fit into the Sonic Youth thing more almost,” Justin said. “Not that level of touring, but just the way they were as people. They were weirdos, like us, I guess.”

From Sara’s tour journal, March 26, 1995:

“The Beatles are playing on our new stereo. Dirty, our illustrious roadie, has recently rediscovered the Beatles as the greatest band of all time. Listening to the Beatles, for me, is always a little strange. It was the music I listened to constantly as a child, so I kind of feel like a little kid when I listen to it, like I’m listening to the Free to Be You and Me record. But because Dirty has a different perspective, he’s been pointing out a lot of the subtle genius of each song. It’s almost like listening to the band all over again. “

The obsession was mostly theirs. Dirty and Vern. “I personally got really into Rubber Soul and Revolver, so we listened to those albums a lot, and then we started listening to the White Album and Magical Mystery Tour and all that,” Dirty recalled. “And then we brought ‘em on tour with us. And we would talk about those particular albums as a group, traveling in a van for hours on end. The discussion was always like, how did they go from mop-top to this? And could an artist still do what the Beatles did? Just totally morph into something completely different?”

In rotation along with the Beatles was the Fall. “There’s that Fall song ‘Repetition,’ which one of us had on tape, a Fall tape we listened to a lot,” Justin said. “And I was thinking, it’s funny, because it’s a cycle, we’re putting out a record and touring, putting out a record and touring, writing these songs. I don’t know if we were getting bored, but we were worried that our records were getting too repetitious, perhaps.”

The tight-knit, cooperative nature of the Olympia music scene had sustained Unwound for several years. But as time went on, Olympia’s insularity felt less like something to cling to than defy. “We were growing up a little bit, getting out of habits that some other people didn’t get out of, trying to get out in the world and get things to happen,” Justin said. “We were getting bigger tours, we had this chunk of change that allowed us to not just be a band that’s stuck in Olympia.

And likewise, the influence thing, we were getting out of the northwest cycle. Even at that time, not necessarily bands on our level, but if you went to Seattle, it was still this weird retrogressive non-evolution of sound. We were more in lockstep with people around the country, trying to find the latest, greatest interesting music, whether it happened in the past or in the present.”

By 1996, “post-rock” had become the fashionable term for a certain breed of band—perhaps most notably the Chicago instrumental group Tortoise—that employed traditional rock-band instrumentation to create music that didn’t adhere to recognizable pop rhythms and song structures. As with most genre tags, post-rock ultimately proved ill-fitting, given the huge stylistic differences between the various outfits to which it was applied. Unwound were never more than fleetingly associated with post-rock, but the same idioms being explored by the bands who were—dub, electronica, jazz, krautrock—can be heard, in one form or another, on Unwound’s fifth album, Repetition.

“At least speaking for me and Sara, we were being inspired by lots of different stuff,” Justin recalled. “Massive Attack, the drum-and-bass scene was starting to happen. There was good hip-hop going on, the Dr. Dre stuff, Tribe. My Bloody Valentine maybe usurped Sonic Youth in some ways as the guitar band to listen to. Free jazz was kinda hitting, too.”

“The jazzer I connected the most with was Mingus, I just went nuts for Mingus,” Sara said. “And two of my favorite records—one is The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady, and the other is Charlie Haden’s Liberation Music Orchestra. I had a tape with Black Saint on one side, and Liberation Music Orchestra on the other. They’re perfect companions to each other. I couldn’t get enough of it.”

Collectively, the band’s mindset was changing. Individually, so was Justin’s. “With Future of What, there was a lot of anger and negativity toward people or life or society or whatever, and a lot of disappointment in the way things turn out, that doomsday mentality,” Justin said. “By Repetition, I’d failed in some relationships and then, right before we recorded the album, my friend committed suicide, so my emotional landscape dropped pretty heavily. I was like, oh, this death thing’s really a lot harder to handle than having some romantic doomsday mentality. Like, when reality hits, you really don’t want to experience that. So I was trying to express that a little on Repetition. Some of those songs are pretty death-oriented, but that was supposed to be the end of that. Like, I’m done.”

The jazzer I connected the most with was Mingus, I just went nuts for Mingus.

When Unwound reunited with Steve Fisk at John and Stu’s in January 1996 to begin basic tracking on Repetition, it was with the full intent that they would use the studio to produce a record unlike any they’d released. Synthesizers were heavily employed. A vibraphone was rented. Echoplex, a vintage tape-delay device Unwound had purchased with their BMG money, became a key part of the sound.

Many ideas came about through basic experimentation. Others were premeditated. On “Murder Movies,” Vern wanted to double his bass with a grand piano. “In my head, the opening always sounded that way,” Vern explained. “A fucking amazing, clear grand piano that you’d hear before the full band kicked in. Those guys both kinda poo-pooed it, but I insisted.”

They didn’t have a grand piano at their disposal, so Vern made do with a keyboard. Blended with the bass, the effect was subtle, but distinct. “If you aren’t privy to the fact that there’s a keyboard, you’re like, why the hell does the bass sound like that?” Justin said. “That’s one of those instances of Vern coming up with something where everybody looks at him like, how’d you think of that? That’s kinda weird. And then later being like, wow, that’s really fucking cool.”

With “Sensible,” Unwound dusted off part of the bass line from “Census,” a goofy, horn-laden instrumental from 1994 that they’d released as part of a 7” on Troubleman Unlimited, and transformed it into a delay-drenched, dubbed-out instrumental. Another instrumental, “Go to Dallas and Take a Left,” was created entirely in-studio. Beginning with a sharp, staccato chord progression, it gradually accelerates and devolves into total chaos, a swirling mess of feedback, saxophone skronk, and freeform drumming.

“We just kept piling on crazy sounds to the end of it,” Sara said. “We had these beautiful little chimes and were like, oh maybe this will sound good, and Vern just grabbed them by the bar that they were hanging off of and shook them like crazy, and they got super tangled-up. He spent the next two days lying on the floor untangling them.”

Repetition would also mark the first time Unwound’s artwork was created entirely with computers, a far cry from the cut-and-paste, homemade feel of their earlier albums. Even The Future of What, which was intended to have a cleaner look than Fake Train or New Plastic Ideas, had still mostly been put together by hand, the text constructed with press-on letters.

Referring to the image at the centerpiece of Repetition’s cover, Justin commented that it was intended to “look like an artifact from the past about the present future. Like, if you look at a Popular Mechanics magazine from the ’60s. The guy in the suit is supposed to be happy because he has this corporate futuristic occupation but we know he’s going to turn into a sedentary puddle of malaise. Having the word ‘repetition’ running down the span of the sleeve was meant to look like the 1s and 0s of binary code. And actually, it’s in there: repetit-10-n.”

Justin rarely discussed the inspiration or intent of his lyrics with anyone, Vern or Sara included. “He didn’t have to,” Vern maintained. “I always knew what Justin was writing about. We were so close for so many years, that if I didn’t know exactly what he was writing about, it didn’t take me long to figure out.”

“Lady Elect,” the last song on side one of Repetition, was a rare exception. “Justin told me it was about someone who had gone, and it was recent,” remembered Steve Fisk. “It was a heavy song to record.”

“I always felt like it was a weird thing to discuss publicly, like, I didn’t really want to discuss my friend’s suicide in a fanzine,” Justin said. “The song title came from a book I was reading on tour about the Shaker church, so there was a religious connotation, this martyr-type thing. I was trying go in deeper and not be specific, disguise it, though maybe I should’ve compartmentalized it and dealt with it in a different way. I probably went to a place where I was crossing the line a little bit.”

I always knew what Justin was writing about. We were so close for so many years, that if I didn’t know exactly what he was writing about, it didn’t take me long to figure out.

That the song is concerned with death is easy to discern from the lyrics, but it’s the production and Justin’s performance that lend the song its emotional weight. The register he sings in is lower than his customary range, giving his voice a tentative, vulnerable quality rather than the aggressively disaffected tone he typically adopted. The vocals on the chorus are doubled, preserving the sense of rawness while also adding heft. Vibraphone delicately ushers in each chord change of the outro. The melodic wail of feedback that ends the track gently soars up an octave and then slowly evaporates.

“When we went on tour, that was a song people always seemed to want to talk to me about,” Vern said. “I think we maybe played it once.”

“We did play it once or twice, but I didn’t like playing it live,” Justin confirmed. “It was emotionally loaded, but it was more that it always felt awkward to play. It has this orchestral sound, and trying to do it as a three-piece, it just lost its oomph.”

On the other end of the spectrum from “Lady Elect” was the album closer, “For Your Entertainment,” which became a staple of Unwound live sets. “That song, I feel like we wrote it in two minutes,” Sara recalled. “We wrote it, and it was done. And I remember feeling a little dismissive of it because of that. It seemed too simple.”

While thematically it’s a bit of a throwback, a media and culture rant of the sort that fueled The Future of What, “For Your Entertainment” lacks Future’s sense of distance. Considering all that had transpired with Unwound professionally over the previous year, a line like “they’ll pick your life apart and throw away your art” could easily be read as Justin admonishing himself. He screams the word “entertainment” as a hook, attacking it syllable by syllable, but despite the force of his voice, he doesn’t sound disgusted or angry. He sounds amused.

“For Your Entertainment” was a hit with Unwound fans, but its adoration paled in comparison to “Corpse Pose,” the song for which Unwound is arguably best known, and for which Vern Rumsey is undeniably best known. “Sometimes someone will be like, oh, I just wrote a song that’s a total Unwound rip-off, and it usually means they’re imitating Vern’s bass line,” Sara added.

To Justin’s mind, the biggest difference in Vern’s approach to music, as opposed to his and Sara’s, was that Vern was an instinctual rather than intellectual player. Appropriately, Vern’s opening riff on “Corpse Pose” came about as a spontaneous, happy accident. “I don’t specifically remember how it happened,” Vern insisted. “I think originally it was just a jam Sara and I were doing while she tuned her drums. And then Justin came in with the guitar.”

Listening to “Corpse Pose,” it’s hard to not have a huge question mark form over the head, as Kazu Makino put it. The bizarre interplay between the guitar and bass on the verses, the wild riff Justin plays on the bridge, the way Sara switches up her snare and hi-hat accents to tie it all together—it may not make sense at first blush, but it works perfectly. It’s an indelible, completely idiosyncratic achievement, something Unwound, and only Unwound, could have done.

“And then when we were recording it,” Justin reported, “Fisk was like, ‘This sounds like the fucking Cars.’”

“He’s got that great guitar line that sounds like it’s an odd meter but isn’t,” Fisk explained, “and I think about the third or fourth time we worked on it, we pulled it up for overdubs, and that line stuck out. And I had my ARP synthesizer, like an original ’70s Stevie Wonder ARP synthesizer, set up in the other room. ‘Buddy Holly’ by Weezer was all over the radio at this time, and it had that signature riff that’s guitar doubled with a synthesizer with what’s called portamento, or glide, and the synthesizer goes between notes.”

Fisk set up the ARP and had Justin mimic his guitar part from the bridge. That was the final piece. “We basically took a pretty simple Keith Emerson synthesizer sound and played it in unison with the guitar part,” Fisk said. “And when you do that, you get the Cars trick that Weezer stole for at least four or five of their hits. And I knew Unwound would love it because it was sick. It was making fun of something that was on the radio.”

An alternate version of “Corpse Pose,” where the synth is mixed louder than the guitar and Vern’s bass runs directly into the board rather than through an amp, was released by Kill Rock Stars as a seven-inch single a few weeks prior to the release of Repetition to help promote the album. (A Repetition outtake, “Everything Is Weird,” is the B-side.) “A friend of mine once told me [“Corpse Pose”] was the KROQ hit that never was,” Justin recalled. “Because it’s got that super-catchy bass riff, and then the whole middle part, but the way we played it, it has this harshness to it, a little bit of edge, a bit of flatness to the voice. I still think a band, a slick band, could play that and it would be a hit.”

Repetition was Unwound’s biggest commercial success during the band’s lifetime. It sold fewer than 20,000 copies.

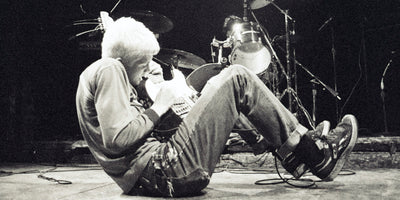

“Repetition should’ve broke,” Steve Fisk believed. “I didn’t think there were any shortcomings with them at all. As abstract as the lyrics were, if a lead singer’s job in a punk-rock band or an alt-rock band is to stand up and be the lightning-rod or point-of-confluence or Jesus Christ burning up on the cross or whatever lead singers get to be, I felt that Justin was as good as it got. When he screamed, it meant something. It was coming from a real place. That should’ve been the record that made something happen, and instead it was kinda lost.”

“In this one way I was ecstatic with Repetition because it broke through and had this additional level of success that they hadn’t enjoyed,” Slim Moon said. “But on the other hand, I’ve always felt frustrated, like mad at the world, for under-appreciating Unwound. I always felt their ceiling should have been a hundred times what they maxed out at. I thought they should have been playing Lollapalooza and festivals, and selling 100,000 records, 250,000 records, and flirting with the radio. And I’ve always wondered, what the fuck, where did it go wrong? Maybe Kill Rock Stars just never got enough clout. Maybe we were never a big-enough label. They should’ve busted out after Repetition, and that’s when their trajectory didn’t go where I expected. And to this day I don’t know why, because I feel like they did everything right.”

“If there’s ever been an example of somebody who needed a manager, it was probably us,” Justin said. “The kind of band that would never have a manager is probably the band that needs one. You need that person who’s the pushy guy or girl who says, I need this to happen and I need it to happen now or I’ll go looking somewhere else. And none of us were like that. But at the same time, we were like, we don’t need to do that, because they’re gonna do it for us. That’s not really how it works.”

“I think there’s this fantasy that if you are creating great art that you will be noticed for your great art, and be lifted to the level of success that you deserve based solely on your creation,” Sara suggested. “When in reality, there’s this whole other piece of self-promotion that comes along with it, actually having the goal of, I want this magazine to write about me, I want to have a video on MTV, I want to make this much money. And that’s not something we necessarily understood to be the case in 1995. The punk-rock thing about being allergic to cheesiness, that lingered with us for a long time.”

“You can’t sell what we were offering to a mass crowd,” Vern reasoned. “We didn’t play music you could dance to; we played music that would affect everyone differently, every song, as opposed to keeping one feeling going all the way through one show. I hate the term ‘emo’ but I think the crowd that we played to felt connected, and felt everything that we played in the way that we felt it, in their own terms.”

“From the beginning we played together easily, but we had started to become the thing I felt was always so special about Unwound, which is that we were the players we were exactly because of the people we were playing with,” Sara said. “The synergy thing was taking real shape at that point. We knew we were a good band, and we had people that loved us, people that really loved us. People that were coming to see us.”

“Vern and I had this conversation when we were getting involved with BMG about having a plan in case things got weird,” Justin recalled. “It was a drunken conspiracy that I don’t think Sara was privy to. We called it our five-year plan or something, and we decided that we would just break up the band in five years no matter what.”

Albeit unintentionally, that’s exactly what Unwound did. But not before recording their masterpiece.

David Wilcox, March 2014