Dü You Remember?

Twin Cities punk rock was at an impasse in the late 1970s. Minneapolis trio The Suicide Commandos, pioneers of the local underground and the first band of its kind in the Lake Superior region, had come and gone by April of 1979. Skinny-tie power pop and new wave acts were forming in droves. In January of ’79, local teen Prince Nelson had been crowned king of Minneapolis’s musical cognoscenti, having headlined the Capri Theater to a sold-out crowd that included a swath of Warner Bros executives who, after the performance, felt confident they’d made the right move by signing the 18-year-old singer and multi-instrumentalist.

Record stores were lined with releases by Donna Summer, Chic, and Earth, Wind & Fire, but also acts from the fringes of Manhattan: Blondie, The Ramones, Television, and Talking Heads. U.K. imports like The Buzzcocks, The Clash, The Damned, Joy Division, and Throbbing Gristle crept into some stores, and were welcomed with great fanfare among underground enthusiasts. Still, in the Twin Cities pickup trucks filled with white working class teens verbally piled on any kid with a short haircut and outsider style. The insult du jour was “Devo!” which was shouted and then followed with threats of a beating.

While the popularity of electrified funk and new wave was growing among the masses, punk rock was alive and well among a marginal audience of record store clerks, club bookers, and college students. Despite mainstream resistance, punk’s next wave was percolating in the Twin Cities. Three friends who bonded over the noises emanating from the East Coast, and from across the pond in the U.K., would play a major role in its enduring and iconic second act.

Known as “The Last City of the East,” St. Paul’s quiet residential streets and empty parking lots provided a blank canvas for friends Grant Hart, Bob Mould, and Greg Norton—three teenagers with an interest in punk rock and nothing much to lose. The trio eventually formed a sort of countercultural bridge between their homebase in working class St. Paul and the more artist-friendly Minneapolis, connecting punkers from both ends of the the Twin Cities spectrum via its earliest shows at clubs like the Longhorn and 7th St. Entry.

The clubs of neighboring Minneapolis eventually nurtured the band’s breakneck rise from formidable hardcore punks to innovators of melodic distortion. But the working-class attitude of St. Paul and its sleepy, suburban landscape incubated the trio in its infancy. The trio railed against its working class cultural apathy, and they did so with the help of a supportive, eager scene of record collectors, amateur recording engineers, and early adopters. Minneapolis may reign as the counterculture capital of Minnesota, but, at its core, Hüsker Dü, with their head-down work ethic and ambivalence toward fashion, was a St. Paul band.

Dü Beginnings

Grant Hart was the youngest of five children born to a German Lutheran mother and hard-nosed, farm-bred father in South St. Paul, a city of about 20,000. The area’s stockyards attracted a significant flow of European immigrants at the turn of the 20th century, and remained an essential part of the local economy until shutting down completely in 2008. After marrying in 1943, Hart’s mother Annetta and father Vernon moved to South St. Paul seeking work. Vernon, who was especially handy, grew up under the tutelage of a sharecropper father, and eventually landed a job teaching industrial arts. He later taught job-training courses in the South St. Paul public school system. Hart’s mother Annetta spent much of her adult life raising children and avoiding conflict with Vernon, who Hart says could be controlling and emotionally abusive. “My father had been an only child and was never really convinced he wasn’t the only human being, period,” Hart said. “He alienated every one of his children. By the time he died, nobody was speaking to him.”

Hart was influenced early on by his oldest sister, Vernetta, who was 12 years his senior, and his godfather, Jeffrey. They were both working artists and demonstrated a perspective beyond the suburban groupthink of South St. Paul—something more hippie, rock n’ roll, and outsider. The collection of rock n’ roll 45s his siblings amassed intensified Hart’s artistic interests, and he spun them fervently on his family’s RCA Victor console.

He began taking drum lessons at age 10 from his older brother Tom, who had his own kit. The pair had been delving into the basics for about eight months when Tom was killed in a car accident when he was just 21-years-old. He’d been working on a local road and bridge crew, and was surveying some curb formations when a drunk driver swerved into his lane. He was killed almost instantly. Hart still feels the shock of the unexpected visit from local police to this day. It was the moment he unwillingly changed from a carefree kid kicking a soccer ball around the backyard to a kid whose older brother—and hero—had died in a horrible way. The pain lingered.

Devastated by the loss, Hart continued to practice at home on his brother’s drum set. It was a natural way to carry the torch. After singing in his family church’s choir, he eventually joined the band at school, starting first on a single snare before moving into rock n’ roll drumming by age 13. His dedication to playing, and his regular practices with the school band, seemed to be therapeutic for his parents, too. They were supportive, almost to a fault. “When they could see I was playing the drums and fulfilling this love of my dead brother, they gave me trust I probably didn’t deserve,” he explained. “As long I was out playing a gig I could get away with murder, really.”

Hart soon joined a cover band and found that he could easily follow along to a range of styles, from The Beatles to polka to Hawaiian music. He explained that he got a lot of work from the group in large part because he didn’t require much rehearsal time. “I provided a good value to the consumer,” he laughed.

Hart also joined the high school jazz band, and was later approached by a Zeppelin-loving classmate seeking a drummer for a new rock band. At the time, Hart was inspired by 1950s-era rock, but he agreed to join anyway. His interest in drumming lead to a greater interest in rock music and culture, and Hart found himself spinning records at home and hitting local record stores to gather as many new releases as possible. By the time he was was 15, he became a regular presence at Melody Lane, a record store in a West St. Paul shopping mall that was part of a local chain. Hart often inquired to the staff about a job, and they appeased him by saying they’d look into it when he turned 16. Getting paid to hang out and listen to records was the stuff of dreams for Hart, as he didn’t see himself doing much else beyond making art and music. Hart waited patiently as the days moved at a mammoth’s pace toward his 16th birthday. While ticking off calendar boxes, he didn’t know that Bill Hass, an employee at Melody Lane, had convinced the manager to hire his friend Greg Norton instead.

Norton grew up the youngest of three kids in Mendota Heights, and attended nearby Sibley High School in West St. Paul. His parents Joe and Dottie met while working in Washington, D.C., and later moved with their kids to Rock Island, Illinois, then Omaha, before finally settling in Mendota Heights when Norton was five. Joe had a sales job with Encyclopedia Britannica and Dottie worked for the U.S. Department of the Interior, in the fish and wildlife division. The pair split when Norton was 14, and he and his mom stayed in the family home.

In high school, Norton got a job at the Norstar Theater in St. Paul, which happened to be next door to a record store called Three Acre Wood. Before and after his shifts at the movie house, Norton perused the bins at the store, and made friends with the manager, John Clegg, who became a music mentor. He introduced Norton to 70s rock, jazz, experimental, and electronic records. For his 13th birthday, Norton’s mom drove him to Torp’s Music, in St. Paul, where he picked out a Hagstrom bass and an Epiphone bass amplifier. He’d been inspired by live performances by The Beatles and The Monkees, as well as the wild sounds he encountered at Three Acre Wood. “I’m not exactly sure when I wanted to be a bass player, but I didn’t necessarily want to be the guitar player,” he said. “I always liked bass. No pun intended, it resonated with me.” He mostly taught himself by ear, playing along to his favorite albums, in addition to scant lessons from a neighborhood kid who played in a band. When he was 16 Norton bought the kid’s Gibson Les Paul Recording bass, the same one he’d go on to play in Hüsker Dü. But at that point, the bass was a casual interest, at best. “Maybe if I’d had a different teacher I would’ve had different practicing habits,” he considered.

In high school, Norton ran with a crew of friends interested in counterculture who pursued art, design, and music studies. When he graduated, Norton enrolled at a vocational school in nearby Red Wing, one of only three schools in the country at the time that offered a program on how to build guitars. He also landed a job at the record store Melody Lane, which felt like a coup. There he got to hang out with his old mentor, John Clegg, who’d gotten a job there, too, as well as his friend Bill Haas, who managed the store.

Norton made a new and totally unexpected friend during a shift at the store. One moment he was grabbing a sandwich in the food court on break, and the next a chubby 16-year-old named Grant Hart walked up and accused him of stealing his job. “I was like, Who is this kid?” Norton laughed. “But then I realized he probably just needed a job, so I was like, ‘Hey let’s go talk to my buddy Bill, I’m sure there’s something for you here.’” And, in March 1978, Grant Hart was hired at Melody Lane, with the help of his new friend, Greg Norton.

They soon bonded over records by The Ramones, Patti Smith, Elvis Costello and Talking Heads. When they weren’t at the record store they hung out at Norton’s house in Mendota Heights, where his mom was surprisingly tolerant of noise and loud music. She was a single mom with a career, so it helped that she wasn’t around to supervise as closely as other parents might have. Hart even moved his brother’s drum kit into Norton’s basement so the two could jam. Even though Hart was underage, they began hitting shows at the local punk-rock bar, the Longhorn, where they took in some of their favorite local acts, like The Suicide Commandos, in addition to touring bands like Blondie and Elvis Costello. Mostly, though, they decamped to Norton’s cinderblock basement to throw darts, smoke pot, and bum around while spinning their favorite new records. Back then, young Norton and Hart, record-store clerks, had no way of knowing that the bass Norton bought when he was 16, and the drums Hart inherited from his deceased brother, would soon come into play on the local scene, in an aggressive and innovative punk trio with aims of Mach 10 speed.

The owner of the Melody Lane chain, Al Brown, also had a small store called Cheapo Records on the campus of Macalester College in St. Paul. As part of their gigs at Melody Lane, Hart and Norton were also often scheduled for solo shifts at the tiny shop, which was only big enough to accommodate one employee at a time. To pass time, they spent hours blasting their favorite records with hopes of drawing in students, who were more amenable to punk rock than the typical mall shopper.

When he wasn’t restocking records and moving a little weed on the side, Hart made a habit of setting up a pair of speakers on the sidewalk outside of Cheapo during his shifts, blaring his favorite new records by The Ramones and Pere Ubu. One day the display caught the attention of a freshman from Macalester College who’d recently moved to St. Paul from upstate New York.

Savage Young Dü

Bob Mould was a tall, serious kid who’d grown up 1,200 miles away in Malone, New York. Like Hart, Mould was the youngest child in a prototypical nuclear family of the 1960s, complete with an abusive father. His mom Sheila and dad Bill stayed together, but it felt tenuous and contingent upon the misdeeds from the family patriarch. Mould described the calamity in his upbringing as much more direct and palpable than what Hart experienced. It was an environment where his father insisted on filling the room with paranoia and nihilism—the world was constantly against him, out to get him—and he channeled those feelings toward his mother and his older siblings, Brian and Susan.

Being the youngest, and puzzlingly exempt from his father’s ire, Mould felt a tremendous responsibility as the only person in the house who could break up the violence. “Even when I was as young as four or five, my brother and sister would beg me to go in and get my parents to stop fights,” he explained. “So I’d go and cry and beg everyone to get along, and things would simmer down for a while.” [1] Because he was the baby, his parents doted over him and vied for his affection, often against one another, which added to the already mounting pressure he felt daily.

Though his father was often the source of his stress, he did introduce a positive element to the family dynamic: music. Mould remembered being educated on 45s from as early as 6, when his father brought home used discs from jukeboxes, courtesy of a local vendor who sold them at a penny a piece. The Who, The Beatles and The Beach Boys provided a refuge from the cacophonous infighting that was bound to occur each weekend in the house. In school, Mould rode solidly in the middle of the social hierarchy—not a nerd, but not terribly popular either. He liked hockey, wrestling, and basketball; and, as he soon discovered, the company of other boys in a way that initially felt confusing.

When Rock Scene magazine ran features on groups like Television, New York Dolls, Patti Smith, and Suicide, Mould felt the gravitational pull toward punk rock. The Ramones’ debut especially captivated him. He was 16 and didn’t yet know what sniffing glue or hustling meant, but he loved the music. He really loved it, and quickly learned all the guitar parts on an $80 SG knockoff his father purchased for him a few years prior. Once his dad realized how serious his son had become about the guitar, he drove young Mould to Bronen’s Music in Potsdam, NY and let him choose an upgrade, for up to a cost of $250.

Mould really wanted a Les Paul, which exceeded the stated price range. Instead he chose an Ibanez Rocket Roll Flying V because it was the same guitar Syl Sylvain played with the New York Dolls. He practiced at home and attended concerts in nearby Montreal, catching acts like Cheap Trick and Kiss. During his trips over the border, he also picked up obscure Canadian punk singles, based solely on their cover art, and added them to the collection of classic rock and American punk singles he’d picked up in nearby Plattsburgh, NY and Burlington, VT.

By the time Mould was nearing his high school graduation, he knew three things for certain: that he loved punk rock, that he wasn’t attracted to women, and that he had to get the hell out of Malone. A scholarship to Macalester College in St. Paul afforded him the perfect opportunity to jet. Plus, he’d heard of a great punk rock band there, The Suicide Commandos. Though the school’s liberal ideology aligned with Mould’s views, his choice to attend Macalester was grounded in finances. “I went because I qualified for an underprivileged scholarship package,” he explained. “My parents would pay only $300 a year for a school that cost well over $5,000.” When it came time for orientation, Mould’s parents drove him all the way to St. Paul from Malone, their station wagon stocked with Mould’s Flying V, amplifier, stereo, and few other belongings.

As soon as he moved into the dorms in St. Paul, Mould picked up the local alt-weekly and began scouring the listings for punk shows. He also took the bus to visit area record stores. Cheapo Records was the shop nearest to his dorm, and Mould responded one day to the wild records blaring from the speakers outside the shop. A clerk he met inside, Grant Hart, had an encyclopedic knowledge of good punk records. As they became friends, 18-year-old Mould introduced Hart to some obscure titles from his days spent growing up near the Canadian border. The two chatted in the store often. Mould shared his singles and Hart introduced him to the newest releases. Hart also noticed that Mould was quick to pick up parts on the guitar after he challenged him to play impromptu in the store one day. By this point, Hart himself was a multi-instrumentalist, focused primarily on drums and keyboards.

Shortly after they met it was announced that The Ramones would open for Foreigner at the St. Paul Arena on November 18, 1978. Hart and Mould decided to go together and on the way they stopped by to pick up Greg Norton. After introductions and pleasantries, Norton’s mom inquired about Mould’s Thanksgiving plans. She promptly invited him to dinner after he explained that he didn’t have any.

After the show, the three young punks occasionally mingled at local shows and at Cheapo Records. Hart and Mould soon became aware, too, that they shared common ground beyond records. Mould was attracted to men exclusively while Hart was bi—or “anything goes,” as one friend at the time put it. Though they quickly learned that they crossed over on the spectrum of sexuality, Mould explained that it was clear, though largely unspoken, that they were friends and only that. Sex was never part of the equation. How Mould really captivated Hart’s affection was through his intuitive guitar playing.

It’s why Mould came to mind almost immediately when Hart was out with friends one night at Ron’s Randolph Inn, a St. Paul dive bar. In late January 1979, Hart and Norton were hanging out at Norton’s then-girlfriend’s house. She had a roommate who wasn’t terribly keen on partying, and so the trio left and went down the street to Ron’s. There they met up with Bill Haas, who they’d both worked with at Melody Lane, and Charlie Pine, who was the manager of Cheapo Records.

Pine was a couple of years older than Hart and Norton, and had graduated from Macalester College at the same time as Norton’s girlfriend, Jeri. “All of a sudden Charlie comes back from the bar and says, ‘Grant, we have to put a band together,’” Norton recalled. Out of nowhere, Pine told the manager of the bar that he had a band called Buddy and The Returnables, which didn’t actually exist, and he landed two gigs at the bar on the spot, on March 30 and 31. Pine played keyboards and, in that moment, essentially forced Hart to be the drummer. For guitar duties, Hart immediately recommended their friend from Macalester College, Bob Mould. Norton didn’t come to mind for bass, as Hart originally thought to approach the bassist of Train, a band he was in at the time that played Beatles covers exclusively.

Soon after that night at Ron’s, Hart picked up Mould from his dorm and brought him to Norton’s mom’s house in Mendota Heights, where his drum kit was set up. Mould noticed a bass in the corner and asked if they could just practice there for night, and if Greg could stand in until they found a bass player. When they were done playing, Hart and Mould decided that Norton, largely self-taught, was a natural fit. The trio played off of one another with ease, working out parts quickly and having a bit of fun in the process. They agreed that they hated the name Buddy and The Returnables—particularly the implication that Charlie Pine was the leader and that they were “returnable.” That needed to change.

Dü The Bee

The name they landed on originated from an inside joke between Hart and Norton, from an evening spent in Norton’s cinderblock basement, which pre-dated Mould’s connection to the band. “Grant and I were hanging out… probably smoking pot, goofing off, being kids,” Norton remembered. “Grant was making up funny lyrics to the song ‘Psycho Killer.’” When it came time for the chorus, “Psycho killer / Qu'est-ce que c'est,” Norton said he shouted out “Hüsker Dü!” instead of the French phrase meaning “What is it?” “It kind of became a thing after that,” he added. “When it came time to start the band, I made the suggestion we call ourselves Hüsker Dü, because it meant ‘Do you remember?’ [in Danish and Norwegian] As in, ‘Do you remember when rock n’ roll was good?’” The name stuck. To make it look tough, they added an umlaut over each u, like they’d seen on heavy metal records. Hüsker Dü was born, and they had two shows coming up fast. So, they began practicing in Pine’s kitchen.

Ron’s Randolph Inn was a tiny, one-story dive in St. Paul, located at 1217 Randolph Ave. The commensurately diminutive stage, only a foot off the ground, was up front near the door. Passersby could see the back of performers’ heads through the front window. Here the quartet of Hart (drums), Mould (guitar), Norton (bass), and Pine (organ) played three sets comprised of covers. Though they had changed the name of the band to Hüsker Dü, Mould, Norton, and Hart didn’t like the idea that Charlie Pine still considered himself the band’s leader. During the second gig at Ron’s Hart, Mould and Norton decided that they were on to something, and made a pact to practice as a trio to see where it could go.

Their debut at Ron’s was under-attended, but not half bad. Soon after the show, Norton approached the owner of Northern Lights, John Carnahan, to see if he’d let the band practice at the store. Carnahan offered the shop’s basement, as long as Norton agreed to clean up the space. After the manual labor, the trio of Hart, Mould, and Norton jammed regularly in the subterranean room, without Pine.

“Even though he liked some of the same stuff we did, [Pine] was a bit more into new wave,” Norton explained. The fact that Pine was a few years older also led the three studied punks to conclude he was a bit more square. So they started working out original songs on their own time, they first time they played any original material. They agreed that their tenure with Pine would have ended right after their Ron’s debut, had Pine not scored another fairly lucrative show for them.

He booked the quartet to play at Cochran Lounge on the Macalester College campus during its annual Springfest. The band received $200 to headline, quite a haul in 1979, so they agreed to revive the Ron’s lineup. Hart stenciled a white suit jacket with the new band’s name, and his mom attended the gig anticipated by Hüsker friends and Macalester students alike. “Cochran Lounge will be jumping this weekend starting with the Springfest concert tonight at 9pm,” a listing in the student newspaper, The Mac Weekly, read. “Jim and the Deltones; Fat Chance; and Hüsker-Dü (sic) will rock for you for $2, drinks included.”

An almost folkloric account of the evening now serves as the Official Firing of Charlie Pine. After tearing through a set of covers, the band had 20 minutes left to play. Faced with an amped-up group of friends and Mould’s college peers, the trio of Hart, Mould, and Norton launched into some original material they’d worked out in the basement of Northern Lights, sans Pine, including the songs “Sex Dolls” and “MTC.” At first shocked by the act, Pine attempted to rally by playing along, wailing incongruently over the loud and fast punk songs his guitarist, drummer, and bassist emitted. During the raucous display, a friend of Hart’s from high school, Steve “Balls” Mikutowski, took matters into his own hands. Without warning, he marched up to Pine, gave him a distinct “thumbs down,” and yanked the cord out of his organ. He then turned to Hart, Mould, and Norton and gave an enthusiastic “thumbs up.” There couldn’t have been a more obvious sign that Pine was toast.

When pressed, the band will admit to these three earliest shows with Pine. But, by all accounts, they consider their debut at the Longhorn as the true start of Hüsker Dü. It’s the club where they’d seen many of their heroes, and where they debuted as a trio.

Soon after forming the band Norton and Hart left their jobs at the chain Melody Lane for two new record-store gigs. Norton took employment at Northern Lights, while Hart manned the counter at Hot Licks Records & Stuff. Northern Lights had the distinction of being one of the only local stores to carry punk imports from the U.K. Hot Licks had a head-shop component that boded well for the two friends’ recreational interests.

As his freshman year was winding down, Mould told Hart and Norton that, if they didn’t get any gigs, he was going home to Malone for the summer. Because they were having such a blast practicing and playing, Hart came up with a plan to deter Mould’s three-month departure. He explained that he’d gotten the band an audition at the Longhorn, and they had to be there at noon the next day. The three friends loaded their gear into the bar, which was serving a quiet lunch buffet—a strange time to hold an audition, Norton and Mould thought. “After about five minutes of us playing, the manager, Hartley Frank, came out and was like, ‘Stop, stop! You can play here as long as you stop making all that noise,” Norton laughed.

There was no audition. Hart had made it all up. But the plan worked. Hüsker Dü landed the opening spot on a four-band billing the next week, and were paid $25 to boot. A number of friends showed up to cheer them on. From then on, they became regulars in the Longhorn’s rotation of local bands. “It was one of those things where we’d flip through Sweet Potato and were like, ‘Hey, shit, we got put in the ad! I guess we got a gig,’” Norton said.

The name on the club’s liquor license was Jay’s Longhorn Bar, located at 14 S. 5th St. in Minneapolis. In the scene it was simply known as the Longhorn or Longhorn Bar. In the late 70s, it was the club to catch the best underground touring acts of the era, and one of the first clubs in America to regularly book punk rock acts. Bands from New York (Talking Heads, The Ramones) and Cleveland (Dead Boys, Pere Ubu) played the long room with the low ceiling, as well as U.K. acts like The Buzzcocks and Gang of Four. The Clash once stopped by the bar after a gig at the St. Paul Civic Center. If ever there was a Midwest equivalent of CBGB, Jay’s Longhorn Bar was it.

The Hüskers played their first show at the Longhorn on May 13, 1979. Peter Jesperson, manager of the influential Minneapolis record store Oar Folkjokeopus (aka “Oar Folk”) and partner in local tastemaking label Twin/Tone, served as the house DJ. Jesperson also helped book bands for the club. If you wanted to release an album, it was commonly known that Jesperson was the man to get a tape to, as he’d worked with local heroes The Suicide Commandos and The Suburbs. He remembered seeing Hüsker Dü at their earliest Longhorn gigs.

“I was always very impressed with them live,” he said. “I was actually kind of shocked by how self-possessed they were, like they always knew exactly what they were doing.” Jesperson once remarked to the band that he thought the Hüskers sounded like a power drill, which prompted Hart to craft a flyer for an early Longhorn gig that featured the buzzing tool.

Jesperson wasn’t the only person whose eyebrows were raised by the explosive trio. Another Oar Folk employee, Terry Katzman, heard about the lock-tight trio that played Johnny Thunders covers, having been tipped off by his friend Chris Osgood of The Suicide Commandos. He saw them for the first time at the Longhorn Bar, just a few months after their debut, and took to them immediately. “They weren’t onstage to talk, play games and tune their guitars,” he said. “They were there to play, and play as smart and as hard as they could.”

Despite early interest from select local tastemakers, Hüsker Dü encountered its fair share of detractors, too. "We just didn't fit in,” Mould later told City Pages. “The Commandos had broken up. People said, 'We've seen it all, blah, blah,blah.' We weren't cool, because we were the only punk band around, and punk was going out of style. But we stuck to our guns." A recording of the band’s third show at the Longhorn, on July 13, 1979, is the earliest audio documentation of the trio’s live performance. It included two melodically driven tracks that didn’t last long in the Hüsker’s live show: “Insects Rule The World” and “You’re Too Obtuse.”

The band’s first demo session happened about two months prior, on May 9, 1979. After composing a few originals, they enlisted Bill Bruce, who’d worked with Hart at a record store/head shop called Hot Licks. Bruce had a small, homespun studio in his basement, and he agreed to bring some of his gear to Macalester College to record the Hüskers. Mould had recently taken a few guitar lessons from Chris Osgood, and they’d become friendly, so he asked him to sit in on the session in a producer role, as well.

At the Janet Wallace Fine Arts Center, Bruce recorded the early Hüsker tracks “Nuclear Nightmare,” “Do The Bee,” “Uncle Ron,” “Don’t Try To Call,” “Sex Dolls,” and “M.T.C.” in a quick, daylong session. A few days later, they decamped to Bruce’s home studio for some vocal overdubs, where the band’s silliness and verve made an impression on the amateur recording engineer. “It reminded me of The Beatles in A Hard Day’s Night, because they were so happy and full of energy,” Bruce recalled. [3]

There was a backstory to explain the behavior. “Do The Bee” was an inside joke that originated with Norton’s friend John Clegg from Three Acre Wood and Melody Lane. He was about 10 years older than the Hüskers, and had told Norton and Hart a story about a time he went to a sort of sock hop-style dance, where he met an attractive woman who had a big beehive hairdo. Clegg asked her to dance. When they took to the floor, the woman’s moves were more like convulsions, her arms, legs, and head shaking erratically back and forth. His impression of the display, what Clegg called “The Bee,” stuck with Hart and Norton. “It just kind of became a thing we would say when we were being crazy,” Norton explained. “And Grant wrote a song about it.” Bill Bruce remembered that, while recording overdubs, Norton and Hart did the Bee, wiggling and rolling around on the floor.

In the fall of 1979, the group enlisted the help of Norton’s co-worker, Colin Mansfield, for another demo session in the basement of Northern Lights. Mansfield had been brought on to help create the shop’s import arm, Twin Cities Imports, and he and Norton had bonded over records. At the time Mansfield was the guitarist in the new wave band Fine Art, which was getting some local airplay. More importantly, Mansfield had a four-track, and he was willing to loan his amateur production skills to the Hüskers.

In what had become the band’s practice space, flyer-making workshop, and general hang spot, Mansfield recorded eight songs over two sessions. An early version of “All Tensed Up,” which opened the Hüskers' first LP, Land Speed Record, appeared in the Mansfield-recorded Northern Lights demos. Many of its other songs, like “Do You Remember,” “Sore Eyes,” “Can’t See You Anymore,” “Picture Of You,” and “The Truth Hurts,” lived and died with a trademark speed that the trio was becoming famous for. Even in their earliest days, the Hüskers were quick to drop tracks, particularly after reviewing tapes of live sets and demos, leaving many early works on the cutting-room floor in the process.

Amüsement

In January of 1980, a new club opened in Minneapolis, at the corner of First Avenue and 7th Street. The Art Deco-style building was originally built as a Greyhound bus station, in 1937. By 1970 it had become the rock n’ roll club The Depot, which hosted artists like Joe Cocker. In 1972, a Cincinnati-based entertainment group, American Events, took over the building and opened Uncle Sam’s, a chain discotheque, complete with a light-up dance floor and shag carpeting. Uncle Sam’s also held the occasional concert, in an attempt to accommodate each end of the popular-music spectrum. By 1978, a former bar-back at the club, Steve McClellan, worked his way up to general manager and booked a couple successful gigs for Pat Benatar and The Ramones.

When disco’s popularity began to wane and American Events pulled out of the space, McClellan convinced the building’s owner to open a live-music venue. It seemed like a tenuous proposition. But, to McClellan’s surprise, they went for it. On New Year’s Eve 1979, the clubs First Avenue and 7th St. Entry made their debut, each named for the street it faced. First Avenue was the larger and more commercial venue, with a capacity of 1,500, which became known as Prince’s preferred room, pre-Paisley Park. It also served as the backdrop for many scenes in The Purple One’s 1984 film Purple Rain.

The Hüskers made their debut at 7th St. Entry, the smaller, 250-person capacity room, on January 3, 1980. They quickly became a club favorite, and played 30 shows in the room that year alone. McClellan said that connecting with Mould led to him booking other punk acts from Chicago and the West Coast. Notoriously modest, he explained that he had no innate talent as a club manager or booking agent, other than his intuition to trust the people around him, who were driving the local scene and making valuable nationwide connections in the process—people like Mould, Jimmy Jam, and Paul Westerberg. But locals thought better of the lovable giant’s claims, and today often cite him as the reason for the rise of the underground in the Twin Cities.

McClellan even mentored Mould on the ways of booking and promoting. In November 1981, Goofy’s, a downtown Minneapolis bar and strip club, approached Mould with the idea of opening an all-ages venue on its upper level. They called it Goofy’s Upper Deck. Mould said that, without McClellan, he never would have known how to handle agents and make favorable deals for bands. Even though McClellan’s clubs were just a couple of blocks from Goofy’s, he was supportive of Mould’s intentions of hosting all-ages shows, primarily for kids who couldn’t yet get into bars. Chris Osgood of The Suicide Commandos remembered that McClellan always treated the club scene more like a nonprofit—it was great for the bands, but maybe not so much for the club’s bottom line.

As Hüsker Dü became one of McClellan’s go-to openers at 7th St. Entry and First Avenue, the band opened for a number of bigger touring bands, like Mission of Burma, and occasionally one of their personal icons, like Johnny Thunders. The Hüskers opened for Gang War, Thunders’s band with Wayne Kramer of MC5, and were disappointed that The Heartbreakers’ frontman was more interested in finding drugs than playing music. Despite their frequent associations with groups at the top of the marquee, they remained eternally willing to support lesser-known names, too, like DNA and Discharge. They’d often accept little payment in exchange for stage time.

The trio synthesized like a group who’d been playing together far longer than a year. They locked in with each other masterfully, while highlighting each member’s distinct playing style and onstage personality. The flat, foreboding sound emanating from Mould’s Flying V was somewhat unheard of in the current landscape of jangly, angular guitar riffs. That combativeness meshed well with Norton’s sludgy bass. The white noise that continually radiated from Mould’s amplifier shrouded the room in a wall of sound, an intentional sonic irritant, the redheaded stepchild of Phil Spector. At the end of each set, Mould and Norton would rest their guitars, with strings still vibrating, against their amplifiers, creating a vexing encore of feedback and aggro posturing.

Hart’s torpedo-like drive behind the drumkit was in stark contrast to his stocky build and earthy appearance (long hair, bare feet). His arms moved so fast you’d swear he had eight of them. Vocals bolted from his chest with a fierce, yet melodic insistence. Though Hart sat at the apex of the triangle the trio formed onstage, positioned slightly behind Norton and Mould, it also made him the centerpiece. His muscular playing and vocal multitasking was both impressive and terrifying.

Mould stood stage left, statue-esque and unwavering in his mission to pack 70 minutes of songs into a 45-minute set. This left no room for banter or niceties. His eyes were often dilated black from taking trucker speed, over-the counter ephedrine pills, or prescription benzedrine, that drivers used to stay awake. His steady gaze was that of an amped-up cat about to pounce. Despite remaining mostly stationary, the ferocity of his voice and guitar hinted at the beast within. To say he was intense was an understatement.

Norton, on the other hand, offered a more buoyant demonstration of the group’s animalistic aggression. Unlike Hart and Mould, Norton was wiry, lithe, and often airborne. He was the first bandmate to pogo and scissor-kick onstage, inspired by photos of Pete Townshend he’d seen as a kid. Norton locked in with Hart like a loaded gun, the pair playing off one another at a sprinter’s pace. The trio wasn’t there to entertain. That much was clear.

The group’s ferocity was met with great intrigue by the Twin Cities scene, but also some resistance. This new hardcore sound—punk played at a bullet train’s pace—was basically unheard of in Minnesota. “I think people were scared of them,” Terry Katzman said. “They seemed pretty menacing from the stage.” However, they soon attracted a small but dedicated fanbase the band affectionately dubbed “The Veggies,” a nickname to describe the six guys who were “very inebriated, generally intoxicated.” The group who came to every Hüsker show and stook up front—Dick and Mike Madden, Tony Pucci, Kelly Linehan, Tippy Roth, and Pat Woods—were some of the earliest proselytizers. Eventually four of The Veggies, Linehan, Pucci, Roth and Woods, formed their own band, Man Sized Action.

In September, the Hüskers had the rare opportunity to work out some new songs at 7th St. Entry without an audience, during an early soundcheck and impromptu rehearsal. The practice session was recorded by their friend and live soundman, Terry Katzman, who happened to tag along. It resulted in a tape the band labeled “Ud Reksuh”—one in a string of silly names they used to describe the contents of Katzman’s tapes.

Even in the group’s earliest days, they were weary of tape trading, particularly of tapes with songs they were still developing. Still, they made a habit of trying out new material onstage, and came to trust Katzman as a local live-recording enthusiast who had their best interests at heart—someone who wouldn’t make secret copies to distribute to friends and fans. “The agreement always was that I could keep the tapes for myself and have an archive of everything they played, and if they ever wanted to access it, they could,” Katzman explained. He added that most of the tapes never left his house in the 35 years he’d collected them.

Katzman’s cassettes were beneficial because they acted as rehearsal tapes that the band could later digest and react to. After reviewing the cassettes, they’d often edit or rework songs, or eliminate them from the set altogether. They became a valuable resource, and were essential to the fast-paced, fine-tuned performances the band became known for.

The Hüskers also received their first bit of real press coverage courtesy of Katzman, in the November 26, 1980 issue of the local alt-weekly Sweet Potato, the precursor to City Pages. Katzman convinced his editors to run a feature on the band in its “Caught in the Act” column. “A familiar guitar hook or riff occasionally surfaces, but before you place it, it disappears,” Katzman observed of their early shows. “The band exists on the sheer strength of their music, nothing else.”

As local momentum was slowly building, and they’d socked away a little money from gigs, the band decided to book time in a real recording studio. In October 1980, Hüsker Dü again enlisted friend Colin Mansfield as producer for a single they intended to shop to local tastemaking label Twin/Tone. Steve Fjelstad, who worked on many of Twin/Tone’s releases, engineered the session. The songs that became known as the band’s first-ever official release, the “Statues” single, was part of a five-song session at Blackberry Way studios. The Minneapolis studio, named after a song by ELO frontman Jeff Lynne’s first band, The Move, was located near the University of Minnesota.

It had been almost a year since Mansfield first recorded the trio in the cavernous underbelly of the record store Northern Lights. In that time, Mansfield and Norton had both been laid off. The owner, John Carnahan, felt Norton was too distracted with the band. Losing the job wasn’t as devastating to Norton as the loss of their practice space. Even though the band had cost him his job, Norton’s mom Dottie was supportive of the band. They moved back into her cinderblock space to practice, where’ they’d begun more than a year ago in preparation for their first-ever show at Ron’s Randolph Inn.

Though the irony of moving back into Norton’s mom’s basement wasn’t lost on the increasingly popular band, booking time at Blackberry Way, and not recording in their makeshift record-store practice space, felt somewhat validating. The tracks captured during this session with Mansfield clearly represent the various rock n’ roll subgenres that inspired them, and served as a sort of disjointed lineup of songs, rather than a proper album, even though the band initially thought to release them as a 10”. Though the band remembers recording up to five tracks, only three survived for an official release, with a fourth track, “Amusement,” added at the eleventh hour from a live recording at Duffy’s, a local club.

Of the songs recorded at Blackberry Way for the “Statues” single, the rhythm-forward, post-punk sound of the title track was the one most clearly inspired by PiL—a comparison the band does not deny. “Writer’s Cramp” veered into power pop territory, and dipped into The Buzzcocks and the skinny-tie sound that surrounded them in the Midwest. “Let’s Go Die” was a straightforward punk anthem laced with a monster hook and a singalong chorus that showcased the speed the band was capable of, as well as their ability to write melodic songs.

After the tracks were mixed and Fjelstad edited them together, Hart made a cassette dub and took the demo to Peter Jesperson of Twin/Tone during one of his shifts managing Oar Folk. Jesperson remembered the cassette containing two songs: “Statues” and “Amusement.” As the resident DJ of the Longhorn, Jesperson had seen the band play its first shows and was impressed by their speed and formidable presence. Still, he had reservations about the cassette. “While I loved punk, I wasn't so interested in the hardcore part,” he said. “I also had reservations because Twin/Tone was a partnership and one of my partners, Charley Hallman, was a little older and had more conservative musical tastes. I was afraid it would be too far out of his wheelhouse. So I passed on it.”

Hart recalled that they seemed fairly confident Twin/Tone would sign the band based on the demo, and that the rejection was a surprise. “A lot of the bands Twin/Tone was working with at the time were more straightforward rock bands with stock influences,” Katzman said. “The Hüskers were on a whole different plane. They were pretty extreme for back then.”

Hart also remembered that “Amusement” was written in reaction to being passed on by Jesperson and Twin/Tone. The lyrics seem to back up the claim: “Won't even beat me/ Yeah, got your letter/ Was it an invitation?/ You created this situation.” The live recording of the track would have been at an October 27, 1980 show at Duffy’s—in all likeliness a few weeks after Hart delivered the demo to Jesperson. Norton added that he’d always heard that three principles at Twin/Tone each liked a different song, and rejected the demo because they couldn’t agree.

Regardless of the order of events, or the actual songs on the demo, Jesperson’s pass helped inform the band’s next steps, leading to a series of decisions that only heightened their novelty in the Minneapolis-St. Paul scene. Rather than shop the demo to labels in other cities, the band unanimously decided upon a do-it-yourself approach—one that would eventually represent the core spirit of punk in the 80s.

Hart, Mould, Norton, and Katzman, who acted as the group’s right-hand man, formed Reflex Records in the fall of 1980. The moniker was a swipe at Twin/Tone, and a sort of mission statement for the group’s commitment to bouncing back from their dismissal. The venture was bankrolled by a $2,000 loan from the credit union where Hart’s mother Annetta worked, an establishment that also unknowingly provided Xerox access and office supplies to the burgeoning label. The official launch of Reflex was marked by the release of “Statues” in January 1981.

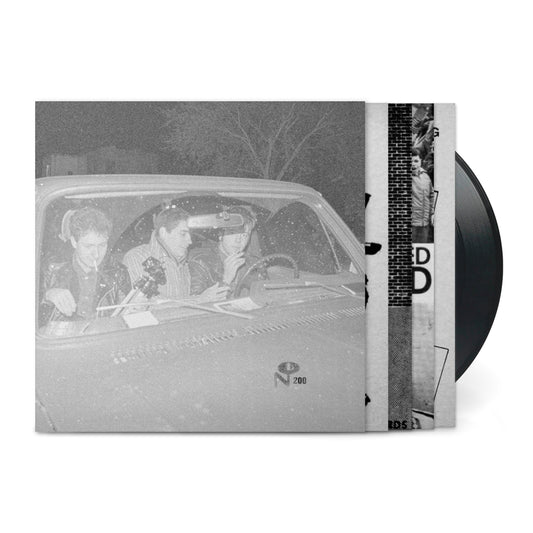

Hart, who had an interest in visual art and graphic design, created the artwork for the “Statues” side of the release, which featured an image of a factory cranking out busts of Chairman Mao. He also created the Reflex logo, which, at that time, featured a plain, sans serif font, not the recognizable razor blade design to come. Thinking ahead, Hart dubbed his design practice Fake Name Graphx, and its name appeared on the inside sleeve. Mould created the “Amusement” side, with pictures of a handgun, kids watching television, and a to-do list. Hart made copies of the black-and-white covers at the credit union. When the 7” arrived in St. Paul from the pressing plant in Arizona, the band bought plastic sleeves, then folded the covers and stuffed the casings by hand.

The self-release of the “Statues” single served as a metaphorical middle-finger to Twin/Tone, but also a boost of confidence for the truly independent band. It also provided incentive to book a national tour, as they officially had merch. In an unexpected but welcome turn, Rough Trade took note of the A-side’s angularity, which aligned with popular British post-punk at the time, and offered to distribute the release overseas.

A Nü Alliance

The Hüskers deeply valued the support of Terry Katzman, Colin Mansfield, Steve McClellan, and others who aided the band’s rise locally. But they increasingly felt the need to branch out to DIY punks living beyond the Twin Cities’ limits.

After about 50 local shows in 1980 alone, Hart, Mould, and Norton were ready to get out town. They traced their road map to Chicago, where a punk scene was percolating around bands like The Effigies, Naked Raygun, and Strike Under. “Hard core from Minneapolis,” read the flyer for their March 21-22, 1981 shows at Oz, the dodgiest DIY spot in Chicago.

Oz was an unlicensed venue beloved by punks that moved three times in its four-year lifespan, due to the city shutting it down for operating without a liquor license and refusing to observe city-mandated closing times. It had no sign out front, and the interior was just as desolate. “The place was a shithole,” Norton remembered. “They were selling amyl-nitrate behind the bar.” [4] When the Hüskers played Oz, the venue was at its third and final location, on Broadway St., about four blocks east of Wrigley Field. To say the situation felt precarious to the young trio from Minnesota was an understatement.

In preparation for the tour, Hart, Mould, and Norton encountered a bit of serendipity. First, Hart was able to convince a local St. Paul car dealer that he needed to test-drive a car for an entire weekend, which was, incidentally, the length of time it took for the band to get to Chicago, play their gigs, and jet home. A bartender at First Avenue hooked them up with a stay at the Radisson in downtown Chicago, courtesy of a brother who worked there. It was a pretty cush situation, the actual shows notwithstanding.

Then there was a chance encounter with West Coast hardcore pioneers Black Flag, who happened to be playing across town on March 23. Dem Hopkins, the owner of Oz, invited Hart, Mould, and Norton to play an after-party for the band. Having heard of the barbarous act founded by Greg Ginn and Keith Morris, the Hüskers excitedly obliged. They drove south to the city’s Fulton Market warehouse district to catch Black Flag’s set at The Space Place, another DIY space run by Hopkins. It was a good chance to not only catch the band for free, but also promote their own show afterward.

Much to the Hüskers’ delight, Black Flag made it to the after-party, and they played a slashing set to the LA punks and their entourage that night at Oz. Their performance was more animalistic than ever, in an attempt to raise the bar of provocation set by their West Coast peers. Mould, fueled by the stream of trucker speed coursing through him, slammed his entire body into a wall while wearing his guitar. Norton seemed to jump 20 feet into the air. Their complete disregard for the trappings of mortality was impressive. Even more memorable, though, was what happened near the set’s conclusion.

Hart threw a can of blue paint from behind the stage, and a woman dressed in head-to-toe leather began scooping it up with one of his cymbals. This, of course, angered Hart, because he’d inherited the kit from his older brother Tom after his tragic car accident. So Hart, who was the most lighthearted and affable Dü at this point, went over to stop her. In the process, he slipped and knocked her into the blue paint, ass first. “A couple of the guys from Black Flag and their crew thought it was hilarious that she had this blue paint all over her black leather pants,” Norton said. “They helped pick her up, but bounced her off the wall in the process. It left a big, blue butt print. They thought it was hilarious, so they did it a few more times.” The night lives on in infamy as “The Blue Paint Incident.”

The performance and subsequent antics created an instant bond between Hüsker Dü and Black Flag. They also made friends with Naked Raygun, The Effigies and Strike Under, as well as Mecht Mensch (later known as Tar Babies) who’d traveled from Madison, WI to catch Black Flag and ended up at the after-party. “We became connected in this network of that time,” Tar Babies bassist Robin Davies explained. “They mentored us and we mentored them. We put on shows for each other, and became really good friends in the process.” At the show the Hüskers passed a tape of a live recording for Black Flag to take back to LA, to share with their friends.

As the bands talked after the show, Greg Ginn suggested the Hüskers get in touch with Mike Watt of Minutemen, who was starting an SST-affiliated label called New Alliance Records. Support from a high-profile band behind one of the best punk labels was a massive confidence boost for the Hüskers. “We promptly called Watt and began to set the wheels in motion,” Mould said. [5] A connection was made.

“All three Hüsker guys would call me and we'd have big spiels,” Watt remembered. “I really dug rapping with all three of them. They were each very distinctive, but also very righteous to talk with.” He added that the calls would often last for hours, and that, in those days, it was the norm for like-minded bands living in different cities to form a telephone support network that connected young punks. They helped each other book shows and find places to crash on the road. “In the old days, we were all very tight,” Watt added. “I was really into that.” Watt also really loved the Hüsker Dü live tape that Black Flag had brought back from Chicago.

Hüsker Dü also connected with the Vancouver-based punks in D.O.A. while opening for them in Minneapolis. Frontman Joey “Shithead” Keithley, guitarist Dave Gregg, and manager Ken Lester helped the Hüskers book a string of six shows in Calgary, their first gigs outside the country. Mould was still a student at Macalester College. Hart and Norton had no steady work. The timing was perfect, and their parents were surprisingly supportive. Hart’s mom provided funding for their tour single, “Statues,” from her job at the credit union; Norton’s mom lent her basement for practices; and, at one point, Mould’s dad drove an old Dodge Tradesman van in from Malone as a gift for the trio to take out for regional shows.

As the Hüskers played locally more and more, they felt a greater responsibility to nurture and promote their contemporaries, especially those who had supported their meteoric rise. One idea was to issue low-budget cassette compilations through Reflex Records. They’d been inspired by an impromptu trek to Xenia, Ohio at the behest of Bob Moore, who ran a small, now-legendary punk label, Version Sound. Moore had the novel idea of recreating the Bullshit Detector series spearheaded by Anarcho-punk collective Crass, which featured a range of demos sent to the group by like-minded acts. The Hüskers traveled to Ohio to contribute the song “Bricklayer” to what became Moore’s first compilation, Charred Remains, which included early tracks by Chicago punks Articles of Faith and Milwaukee’s Die Kreuzen, among others. The tape remains one of the most coveted collections of early Midwestern hardcore.

Reflex Record’s first comp, Barefoot & Pregnant, also became legendary among collectors. Originally dubbed to a run of 200 copies, the comp featured Loud Fast Rules—the band that became Soul Asylum—and the Hüskers’ friends in the Veggies fan group who had formed Man Sized Action and Rifle Sport. The Replacements contributed a cover of “Ace of Spades,” while a one-off “supergroup” of Mould, Chris Osgood, and Tommy Stinson from The Replacements recorded the pub rocker “Let’s Lie” under the name Tulsa Jacks. Mecht Mensch rounded out the B-side, along with the Minneapolis locals Red Meat. When it was released in the spring of 1982, the label only sold about 100 and gave the rest away to bands. Today, a mint copy fetches about $700 on eBay. The Hüskers also eventually released singles and LPs, as well, by their friends in Rifle Sport, Final Conflict, Man Sized Action, Ground Zero, and Articles of Faith.

In early 1981, Hüsker Dü and The Replacements, who’d been signed to Twin/Tone under the tutelage of Peter Jesperson, were the go-to bands for local bookers. They took turns opening for national touring acts, as well as each other. While much has been made of a supposed rivalry between the two groups, the Hüskers and Katzman are quick to point out that they were on two very different paths. The Replacements were a more straightforward rock n’ roll act with zero DIY ambition. Hüsker Dü were an evolving punk act veering into the realm of hardcore. “There was no resentment at all,” Mould explained. “Things couldn't have worked out better. Peter Jesperson was a big supporter of both bands, and I think healthy competition is good.” While they were keen on any opportunity to play locally, the Hüskers knew they had allies outside of Minnesota’s pastoral confines, and intended to reach beyond the comforts of home. In June, they headed north to Canada.

Hüsker Breathrü

Before departing, the band’s van had broken down, so Norton arranged for a rental. Because his name was on the agreement, he did the lion’s share of the driving, which was fine by him. Norton also handled most of the business for the band, wrangling money and booking shows from gas-station payphones. Mould was solitary and intense, fingers yellowed from a nonstop stream of cigarettes, while Hart remained the group’s lighthearted presence who played barefoot and never knew a stranger.

The oft-discussed scrutiny of American punk bands by officers at the northern border became a reality when the trio’s Canadian work permit was sent to the wrong office. At the Manitoba checkpoint, near Winnipeg, they were instructed to turn back around to North Dakota and drive to the next stop, in Alberta, where their papers had been sent in error. After looping back to the U.S. side, they were met by a group of dubious American border patrol agents who didn’t like the cut of their jib, particularly Hart, with his leather jacket and bleached-out hair. The mass of gear in the van didn’t help, either. The agents searched the vehicle and then summoned Norton into their office. “The officer had something on the table that was huge, that he claimed were marijuana seeds,” Norton said. After insisting that the van was a clean rental, and that there was no way that thing on the desk was marijuana, the officers finally let them go. “That was after a couple of hours,” he added.

The band finally made their way to Alberta to pick up their working papers, and then on to Calgary for a run of gigs. The Calgarian Hotel, where they were scheduled to play, was a derelict, five-story structure that hosted punk rock bands in an even more derelict part of town. It later burned down, in December of 1986. The dive had hotel rooms on the upper floors and a bar on the main floor where townies hung out during the day, chatting and depositing tears in beers. One of its noted distinctions was the large concentration of native people who bellied up to the bar, mingling with the Anglo, rural cowboys. Bruce McCulloch, the Calgary-born member of the Kids in the Hall comedy troupe, once memorialized The Calgarian in a joke: “First we took their land, then we took their bar.”

By 9pm each night, punks poured in for local bands and the occasional touring act. A room upstairs was included as part of the Hüskers’ payment. For six nights, from June 22-27, they played four sets a night and slept upstairs, witnessing the occasional brawl and stab wound. Despite the dicey setting, playing 24 sets in six nights had a miraculous effect on the band, which became tighter and faster with each sundown.

From Calgary they drove to Vancouver, where they were hosted by D.O.A guitarist Dave Gregg. There, they played three shows, two of which were at the Smilin’ Buddha Cabaret with locals Insex. Like the Hüskers, Insex had opened for a number of high-profile punk acts, including The Ramones and Siouxsie & The Banshees. After the marathon in Calgary, which included a steady intake of alcohol and methamphetamines, the Hüskers were downright savage. Mould and Norton rarely stood still, and Hart made a habit of knocking over his beloved heirloom kit at the end of each set. Audiences were particularly impressed when Mould and Norton jumped in unison, soaring above Hart’s wailing arms.

After the three-show run in Vancouver, their friends in D.O.A. dialed the punk network in Seattle to help them secure a few shows in the Pacific Northwest. They nabbed four Seattle dates: two at the now-defunct club Gorilla Room, one at WREX, and one at The Showbox. “There's nothing wimpy about Hüsker Dü,” proclaimed a review in the Seattle zine Desperate Times. “They come on with such force and energy, energy that builds with each song, that I felt as though the bar would explode at any moment.” They were placed as openers for The Dead Kennedys at The Showbox. After bonding with frontman Jello Biafra, he invited the band to his home in San Francisco for two weeks. He offered this take on the Hüskers to an interviewer from Maximum Rocknroll, which appeared in its second issue:

"I think it's more a case of, like, standing in the dentist's office waiting to be drilled on and not knowing what's going to happen next. There are a lot of people who dance at first, and then realize that maybe this just wasn't familiar and then stopped. People do not go to the back of the room and talk to their friends, they just kind of freeze."

In San Francisco, Biafra helped the Hüskers secure shows at Mabuhay Gardens in North Beach, known by locals as the Mab or the Fab Mab, which was considered a West Coast take on CBGB. The booker, Dirk Dirkson, acted as the ringmaster each night, introducing local bands and bigger-name touring acts with a sardonic wit that punk denizens of San Fran came to love. The Hüskers joined bills with 7 Seconds, who’d release a single on Biafra’s label Alternative Tentacles in 1982, among others.

They then made a quick jaunt to Sacramento before heading to Reno, where they played with D.O.A. and were mistakenly billed as Who Screwed You. They played one more show at the Fab Mab in San Francisco with The Dead Kennedys before deciding to drive nonstop back to Chicago. The trucker speed they were gobbling certainly helped the commute.

After arriving in Chicago, they played at O’Banion’s, a former mob hangout in the River North neighborhood that had changed hands a number of times before turning into a punk club in the late 70s, after the premier local hub of punkers, La Mere Viper, burned down. There was no stage and no PA system at O’Banion’s, but the Hüskers welcomed the opportunity nonetheless.

Morale was at an all-time high after the trio pulled off their first national tour—and they had a pool of great songs to boot. On their way home to Minnesota, they made plans to capture the triumphant spirit and record their first LP during a homecoming performance at 7th St. Entry. It was a cost-effective means of laying down the piles of songs they’d rehearsed ad nauseam on tour, while also memorializing the pivotal DIY sojourn they’d christened “The Children’s Crusade.” When they departed in mid-June, they were young rising locals. When they returned, nearly two months later, they were formidable men.

Terry Katzman helped spread word about the homecoming gig at 7th St. Entry, which took place on August 15, 1981. “Hüsker Dü Returns Home,” the flyer all but cheered. They separated the night into two sets. Steve Fjelstad from the “Statues” session at Blackberry Way was set to record the performances on a four-track reel-to-reel, at a budget of about $300. Katzman assisted with the mic-ing and setup. Of the two sets, the first was meant to illustrate the brutality and hustle they’d experienced on the road in Canada and the West Coast—and it was convincing. The audience was stunned by the raw adrenaline pumping through the trio, who’d already been the fastest band in town before leaving for the tour.

The second, moodier set was purposefully slower, allowing each member room to spread out in their respective parts—and catch their breath between tunes. For comparison, they played eight more songs in the first set, but in almost the same amount of time.

After the show, Fjelstad went to Blackberry Way to make a rough mix of the first, absolutely brutal set. The band called it Land Speed Record as a way to canonize their two-month journey—one fueled by ambition, beer, and generous helpings of drugs. As Mould put it, “We covered a lot of land. We took a lot of speed. And we made a record.” [6]

Afterward, Mould took the tape to a Christian mastering house in Gary, Indiana—for the irony of it all, and also so he could visit a lover in nearby Chicago. The group then sent copies to the folks at SST, as well as Mike Watt, for consideration on New Alliance Records. Watt and his bandmate and best friend, D. Boon, were wholly energized by what they heard. “We kind of thought it was like really fast Blue Oyster Cult,” Watt said. “I know that sounds crazy, but me and D. Boon were huge Blue Oyster Cult fans. It’s the band we saw the most in the 70s.” Land Speed Record became New Alliance’s seventh release. “I will always love the Hüsker cats for trusting us with that,” he added. “We loved their sound. Our Double Nickels On The Dime was totally inspired by them a few years later.”

The cover the band chose was intentionally political: an archival photo of caskets returning to the United States from Vietnam, draped in American flags. It smacked of anti-war sentiment, but also the fatigue they felt upon finishing their first national tour.

In the months leading up to the release, the Hüskers reprised the Land Speed Record set at the Entry at least a couple more times. A September 5, 1981 date captured the spirit of the inaugural performance, albeit at an even more frenetic pace. Land Speed Record hit shelves in January of 1982, and 7th St. Entry hosted the band for a release celebration. The next day they took off for a pair of shows in Chicago, then bounced between Minneapolis and various Midwestern cities until returning to Canada in June.

In the six months between releasing Land Speed Record and revisiting The Calgarian, the trio returned to Blackberry Way for a breakneck daylong session with Fjelstad. They laid down five tracks for a single they’d already agreed to release on New Alliance. “In A Free Land,” “What Do I Want?,” “M.I.C.,” “Target,” and “Signals From Above” were largely written on the road during the Children’s Crusade tour, or shortly after the band’s homecoming. They were eager to document their songwriting evolution, and to have another single to sell on the road during an extensive summer tour across the West Coast. In exchange for New Alliance releasing another record, they offered to put out a Minutemen single on Reflex Records. Tour-Spiel, a live EP of four covers recorded in Arizona was released in May of 1985.

“In A Free Land” became the A-side of a Hüsker 7” released on May 1, 1982. The lyrics focused on resistance to the censorship and groupthink in Ronald Reagan’s America, represented Mould at his most political. Hart’s “What Do I Want?” is a bit more avant-garde and meditative, albeit through the lens of screeching terror. It’s an extension of the alienation he felt, having been lumped in with the hardcore movement at the time. “I was never able to satisfy a search for a voice in that medium,” Hart said. “‘What Do I Want?’ is the closest thing that I could do with hardcore.” [7] “M.I.C.,” another political rant from Mould, rounded out the B-side. The cover of the single was a continuation of the Land Speed Record aesthetic. Credited to Hart’s Fake Name Graphx, it features a photo of a flag-burning the group had staged at Macalester College.

Who Screwed Yü

By the time the band left for its second national tour, Mould had dropped out of college. Hart and Norton remained unemployed, a point of contention with their parents. Still, they couldn’t have been happier about life as full-time musicians, even if they were living hand-to-mouth. They booked a two-month summer excursion in support of Land Speed Record and In A Free Land, but also to record a new, full-length album in Los Angeles with their friends at SST. Despite the growing punk network across the western United States, the tour remained a testament to the uncertainty of the road—one moment the band was playing to a sold-out crowd, and the next to 15 confused onlookers who were there for the new wave act that followed. After their first encounter at the Canadian border, the Hüskers swallowed their entire collection of drugs before reaching the checkpoint, and proceeded to motor through to Calgary.

After two dates at The Calgarian Hotel, they returned to Vancouver and San Francisco, where they stayed with Jello Biafra and his wife for a few days—a pleasant contrast to the seedier digs their $5-a-day allowance afforded them. The Hüskers spent their final night in the Bay Area in a former Hamm’s brewery ruled by the local political hardcore band MDC, where kids slept in steel tubs and skated through the night. When they weren’t on the road they watched and analyzed as many televised professional wrestling matches as possible, their one obsession outside of speed and songwriting.

From San Francisco, they headed south to San Diego for a gig with Battalion of Saints, and then on to Torrance. In Los Angeles, they met up with the full SST crew for the first time: Greg Ginn, Chuck Dukowski, Henry Rollins, Joe Carducci, and Mugger. The mission was to record another full-length album with SST’s eccentric house producer, Glen Lockett, better known as Spot. During a session at Total Access Studios in Redondo Beach, the band recorded tracks for its first studio album, Everything Falls Apart. The Descendents were there, too, recording their full-length debut, Milo Goes to College. The Hüskers took the graveyard shift to get a better rate, and they slept on the floor at the SST office to save money. Mould remembered that Henry Rollins, who’d recently joined Black Flag, slept at the office, as well, and offered to give up his bed space on the floor under his desk during their stay.

During their four days in Los Angeles, the Hüskers worked at a speed commensurate with the fistfuls of uppers they sloshed down with beer. Though there was little time for experimenting, the group explored a few new techniques. Robin Davies, their friend from Tar Babies who was along for the tour as roadie, remembered singing backing vocals into a mic they’d placed inside a piano. Mould had the idea to include a cover of Donovan’s “Sunshine Superman,” but encouraged Hart to sing it, knowing his upbeat, more melodic vocal delivery was a better match for the tune.

When they weren’t in the studio, the band hung out and played basketball with Greg Ginn and his brother Raymond Pettibon, who created the stark illustrations that adorned many of Black Flag’s releases. The Minutemen also dropped in, and the group of six bonded over politics, music, and general tomfoolery. By now, the Hüskers felt at home in Southern California as much as they did in the Twin Cities.

Shortly after their foray in the studio with Spot, the Hüskers headed to Texas. After a show in Dallas, they stayed with King Coffey (née Jeffrey Coffey), who, shortly before joining Butthole Surfers, played drums in the Fort Worth hardcore band The Hugh Beaumont Experience. Coffey lived with his mom, who prepared piles of white-bread-and-Velveeta grilled cheese sandwiches for the group—a surreal scene, when they recall it now. In Austin they were pelted with beer cans, a local’s way of showing affection that was confounding to Mould, who threw them right back with the intensity of an MLB pitcher. After blowing through Houston, they headed back to California for a show in San Diego with Minor Threat, who they’d seen at O’Banion’s in Chicago. To show they disagreed with the D.C. group’s straight-edge ethos of no drinking, no drugs, and no sex, they scattered a bottle of white aspirin tablets all over the stage right before Ian MacKaye and crew played. They bid farewell to their SoCal brethren with a showcase at L.A.’s Olympic Auditorium on July 17, 1982, along with Black Flag, D.O.A., 45 Grave, and Descendents. The audience climbed the PA and dove 15 feet into the crowd, the stuff of 80s hardcore lore that is actively eschewed by clubs today.

Hüsker Dü returned to the Midwest with hopes that Joe Carducci, SST’s operations manager, would give the thumbs-up to release Everything Falls Apart as their debut for the label. But for reasons that remain unclear, he passed again. Instead, it became the first Hüsker Dü LP on their own Reflex Records, financed by money they’d earned on the road, combined with another small load from the credit union where Hart’s mom worked. They pressed 10,000 copies in two runs of 5,000. The sides were labeled “black” (A-side) and “blue” (B-side) in the dead wax, in lieu of traditional A & B labels. The earliest pressing included a now-coveted lyrics sheet printed over a blue image of a little girl playing with blocks. The black-and-blue cover, credited to Fake Name Graphx, featured Rorschach inkblots representing each song. Its cover and lyrical content were a notable departure from the political themes of the previous two releases.

The SST influence on the record is recognizable in the faster songs, as well as the quality of the recording. It’s no secret that the band had Black Flag’s Damaged on heavy rotation in the months leading up to the recording session. But there were also undeniably melodic moments as well. Tracks like “Wheels” and “Signals from Above,” displayed flashes of dissonant experimentalism.

Mould’s thick guitar sound, Norton’s increasingly complex basslines, and Hart’s stampede-style drumming had clearly evolved. “What you hold in your hands is a musical document of those times and, in this writer’s opinion, one of the greatest punk records ever,” Terry Katzman wrote in his liner notes to a 1993 reissue. “Even now, the power and diversity of these songs rival anything from today’s alternative camp.”

The urgency of the songs embodied the spirit of hardcore at the time, as well as the energy of their live shows. And there’s a good reason for it: All of the songs had been written and rehearsed on the road. The band’s numerous excursions across western states were particularly good for Mould, who cranked out new songs at a feverish clip. “I was feeling inspired by meeting and playing shows with so many likeminded bands,” he added. Almost nothing was added on or reworked in the studio. The commitment to first takes—or as few takes as possible—had become a trademark, the product of budgetary necessity and a commitment to maintaining their usual tempestuous pace.

While their fast clip and DIY ethos represented hardcore at its purest, the group was increasingly skeptical of the dogma of the movement, and the anti-establishment “rules” that, to them, began to reek of a new establishment. As such, some of the lyrical content of Everything Falls Apart is a personal cry against the hardcore metanarrative. Unlike In A Free Land, Mould wasn’t railing against Reagan; he was expressing himself through the lens of his experiences. “Punch Drunk” provided a commentary on the nonsensical violence he witnessed at hardcore shows, and “Target” and “Obnoxious” took aim at the snotty art-school kids who taunted punks. The rejection of hardcore’s more strident principles is particularly evident on Norton’s “Blah, Blah, Blah,” as he was especially tired of being told what to do. As Hart told Maximum Rocknroll: “The only labels I care for are record labels.”

By comparison to the band’s previous releases, Everything Falls Apart flew off of shelves, and the band knew they would need a wider distribution network in the future. It was the band’s most cohesive and accessible album to date, and their years of road-dog touring had connected them with audiences across the country. News of the rising American hardcore movement had even traveled overseas. New Musical Express offered this assessment of the Hüskers’ latest, in its April 23, 1983 issue:

"Hüsker Dü's 'Everything Falls Apart' (Reflex) is yet another Spot production. This mighty Minnesota unit made a great EP last year called 'In A Free Land' and are one of these power-drill trios who sound like ten guitars. 'Everything Falls Apart' hangs together on this formidable power, and is unbelievably fast and frenzied. Not as rhythmically protean as MDC, nor as ingeniously volatile as the Zero Boys, but pretty intoxicating all the same."

Despite some sour feelings about being lumped in with the hardcore hive mind, Hüsker Dü signed with SST in the fall of 1982. The discussion had been percolating since the release of Land Speed Record, but had stalled in the wake of the band’s intense touring schedule, not to mention the release of several records on their own Reflex Records. Ultimately, Hüsker Dü became the first act outside of the West Coast to be offered a deal by SST.

Some of SST’s most popular bands at the time, like Meat Puppets and Descendents, couldn’t tour because they remained committed to keeping jobs and pursuing college degrees. The label needed the financial support of a group that was willing to be a road warrior, one that would tour extensively in support of its records, which was the Hüskers’ model from the start. Their ability to fill each other’s respective needs aside, SST felt like home to the Twin Cities punkers. It also afforded them an autonomy from the “Minneapolis” tag so often applied to them—an area they loved and remained loyal to, but technically no longer needed.

The timing was good, too. No sooner had they signed the metaphorical dotted line with SST than they had an entirely new batch of songs, primed on the stages of Minneapolis and ready for the studio. On December 14, 1982 they played 7th St. Entry in what was dubbed the “Hüskers Goodbye” show, their last gig before heading back to Los Angeles to record with Spot. That night they threw a few nostalgia bones to the audience—pre-Land Speed Record tracks like “Old Milwaukee” and “Russian Safari,” for example—before charging full steam ahead into highlights from each subsequent album. Included, too, were most of the 12 songs they were about to record in L.A. for the Metal Circus EP. The plan was to play a few shows on the way out, record with Spot, then roll through a month-long tour across California, Arizona, Texas, Oklahoma, and Illinois in support of Everything Falls Apart.

Hüsker Dü’s DIY tunnel vision and commitment to touring had paid off. The possibility they saw in an official partnership with SST outweighed any reticence they had about the potential albatross of its doctrine. In its refusal to be defined by the sanctions of hardcore, while at the same time becoming an essential spoke in the movement’s cultural wheel, the band carved its own path through the underground. As calendars turned to 1983, they embarked on what would become the second book in the Hüsker Dü trilogy of recorded identity, leaving their own Reflex Records in the rearview.

-Erin Osmon, May 2017

1. Bob Mould and Michael Azerrad, See A Little Light: The Trail of Rage and Melody

(New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2011)

2-4. Andrew Earles, Hüsker Dü: The Story of the Noise-Pop Pioneers Who Launched Modern Rock

(Minneapolis: Voyageur Press, 2010)

5-6. Bob Mould and Michael Azerrad, See A Little Light: The Trail of Rage and Melody

(New York: Little, Brown and Company. 2011)

7. Andrew Earles, Hüsker Dü: The Story of the Noise-Pop Pioneers who Launched Modern Rock

(Minneapolis: Voyageur Press, 2010)