INTRODUCTION

Never walk behind the pulpit in a Black Church. It’s an old tradition rooted in reverence and a little superstition that many don’t hold to today. But just in case, don’t do it. The pulpit is a sacred space held by those daring enough to commit their lives to preaching and singing. It’s a throne between the Almighty and man. It’s where Pastor T.L. Barrett became a maestro of gospel and a conduit for the word of God.

Gospel music is the revolutionary love child of a rebel and a thief. The rebel: Negro spirituals, the songs created in fields by enslaved people in acts of perseverance, those who dared to imagine freedom with a greater and more powerful force than the hatred of those who suppressed it. The thief: the African-American faith tradition, stolen from the slave masters’ bibles and recast under the thicket of the hush harbor, marking one of the most crucial Black American survival skills—taking something from the hands of evil and using it for good.

It grew to become the living sound of faith, sung in Black Churches, and made powerful not just by a solo voice, but by the collective voices of the people. This resilience through unity rose above the noise of hate and burden. And from this tradition came Barrett, holding sacred space for our faith but also the good of our humanity. His journey was as much in the streets as it was in the church. He spent his early adult years in New York City playing piano in nightclubs and working odd jobs while in search of his life’s meaning. He found it in ministry and gospel music, as a gifted orator and inspiring choir director and songwriter.

By his late twenties, he was a leader of the people, a preacher that embraced the activist traditions of Fred Hampton, Martin Luther King Jr. and Rev. Jesse Jackson. Barrett uplifted Chicago’s underserved through unwavering commitment, building outreach programs in the Robert Taylor Homes public housing complex on the South Side, and working with Jackson’s economic development program Operation Breadbasket. The children in Barrett’s Youth for Christ Choir were exposed to the worst of the world, but brimmed with unquenchable hope against all odds, for their collective faith and Barrett’s belief in them.

His life also reflects one of the faith’s most vital teachings: the radical power of forgiveness. In 1988, Barrett was ordered to repay more than one million dollars in restitution for an alleged pyramid scheme. He’s always denied any bad-faith dealings, and to this day it’s unclear whether the plot was an ill-intentioned come up or ill-executed attempt at making a better life for the disenfranchised. All grays with no room for black and white. But his flock forgave his alleged sins, and today Barrett still leads his congregation at 5500 S. Indiana Avenue.

An imperfect man who made exceptional music, Barrett embraces the city, its talented but disenfranchised, and its wandering and hurting. And he doesn’t just issue an invitation, because that’s not Barrett enough. His outreach via his church and his music is so spirited, so earnest, it’s like he loaded his pulpit on the 47 bus to Harold’s Chicken, got his order fried hard with mild sauce, put it in our laps, without napkins, and prayed over the meal before we ate so we are nourished physically and spiritually.

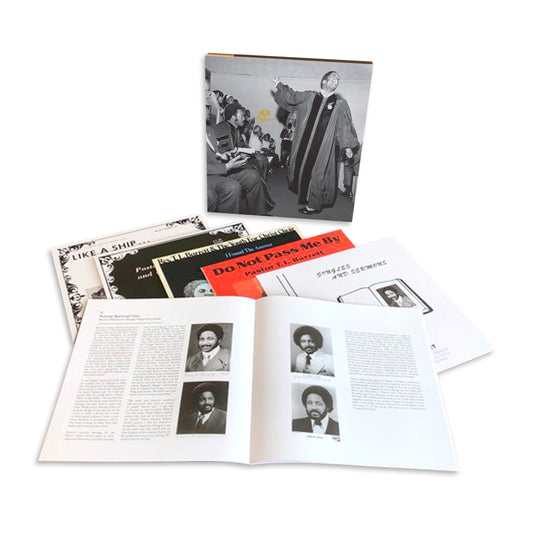

Barrett self-released his debut album Like a Ship... (Without a Sail) in 1971, and it didn’t gain traction until some 40 years later, after the controversy, lawsuits, local fame and even an appearance on Family Feud. Its relative popularity now is perhaps his greatest redemption story. A righteous man falls down seven times and still rises, while the wicked man falls into ruin, the good book says.

Now, when we talk about Barrett’s music, we’re often conveying the distinct joy of having our favorite thing for the first time, that moment the sounds of his church became a staple in our homes. This box set offers the most comprehensive version of that, from his lauded first album to lesser-known singles and his funny and stirring sermons. It’s all here to become our new favorite. Barrett is a reminder that we can be all things to all men—a revolutionary, a believer, a sail-less ship made right in the storm. Through him we are devout believers in the face of uncertainty, hands raised in defiance. Just don’t walk behind the pulpit.

-Aadam Keeley, April 2021

I. Of Saints and Sinners: T.L. Barrett’s Divine Pact

The transformative presence of God does not discriminate. It bolsters the glory of saints and fosters the redemption of sinners. It revives forgotten spaces and restores hollowed souls. “I have swept away your offenses like a cloud, your sins like the morning mist. Return to me for I have redeemed you,” scripture reads. For Pastor T.L. Barrett, God’s promise carried him when the physical world would not, when those meant to guide and nurture him threw up their arms or tragically fell away. It lifted him from valleys, persevered through the passing of decades, and helped him reach his potential.

When Barrett was just 16 years old, growing up poor, unfocused and rebellious on Chicago’s South Side, the high school he attended declared him a lost cause. “The counselor made one pronouncement that made the difference in my life: She told me I would never amount to anything,” Barrett explained. “The day I was kicked out of Wendell Phillips Academy High School, I walked from 39th and Indiana to 57th and Indiana, and I made a deal with God. I said, ‘I will keep my mind keen and keep my body clean if you reveal yourself to me.’” Soon after, his beloved father died suddenly, leaving the family with little more than good memories. Each of these shifts proved tectonic, rattling Barrett’s foundation and forcing an autonomous reckoning. “I started calling upon my inner resources, and I set out on a quest to improve my life,” he said.

By age 24, Barrett had found his calling. After graduating from seminary, he became the pastor of a Baptist church on the South Side with a particular focus on youth outreach, an ascent that was part mea culpa, part retaliation. “I had decided that the counselor’s negative opinion would not become a positive fact,” he said. The church’s Tuesday night meetings—dubbed the Youth for Christ Gathering—attracted kids ages 12 to 19 from all over the city. The pastor saw himself in the youth, who thirsted for the guidance and community the church offered, but were overlooked and forgotten by the underfunded local structures, and the hegemonic and discriminatory broader systems, which were supposed to support and protect them. “Eventually I wasn’t satisfied with just improving my life,” Barrett added. “I wanted to prove that other young people could be saved.” As the spirit continued to move him, Barrett’s mission also shifted from the personal to the collective.

This communal outlook informed Barrett’s sermons, but also the singular music he recorded with his 45-piece Youth for Christ Choir, formed during those Tuesday night meetings. Barrett’s gospel songs are insistent, ecstatic and filled with unexpected layers and turns. So much happens at once, it takes a moment to notice the way he morphs his pronouns. But that simple rhetorical gesture speaks volumes. As “Like A Ship” slowly builds, his “I” becomes a “we.” That same shift happens again on the inspirational “You May Not Need Him.” On the rapturous “I Shall Wear A Crown,” the narration slides from “I” to “you” and back again. It’s as if, with the simplest of words, Pastor Barrett sets himself on an equal musical footing with his choir, who respond with joyful high-pitched enthusiasm and precision beyond their years. Throughout, his overarching message is that the individual and the community energize each other as they work together. His message was so potent that his church attracted some of the era’s local luminaries, including the legendary Donny Hathaway, as well as Larry Dunn, Andrew Woolfolk, Philip Bailey and Maurice White of Earth, Wind & Fire.

Throughout the 1970s, Barrett saw boundary lines that went beyond his city’s historic segregation and he reached across sharply divided terrains to make his voice and congregation heard. At a time when rising Black business executives and politicians set new examples for leadership, public housing towers showed how much poverty and racism remained entrenched. A range of African American Christian denominations reflected diverse theologies, class differences and, oftentimes, the music that resulted. Then there was the music itself: An older tradition of gospel— which had deep Chicago roots—was giving way to a youthful contemporary sound. Barrett not only moved among these divergent milieus, he allowed each of them to become a part of his work. They fueled the collective.

By the ’80s, the faith Barrett lived by, and the spiritual community he built, proved a great redeemer. In 1989, Barrett was ordered to make full restitution of more than 1.3 million dollars, money accrued in an alleged pyramid scheme. According to a report in the Chicago Tribune, mostly anonymous callers told investigators that they hadn’t received payments after being promised returns of $12,000 if they invested $1,500 and recruited other investors. Barrett has always insisted that the money was collected honestly in the name of local development. And amid the controversy, he doubled down. “Our effort and our intentions are above board and we are going to proceed with our community development program,” he told a Tribune reporter in July of 1988. “We are going to cease, as the attorney general said, the pyramid aspect of it.”

As a guarantee, the court placed liens against Barrett’s home, his Life Center COGIC and two church-owned vacant properties, and required that he pay the ordered sum by the fall of 1998. No civil or criminal charges were pursued, and Barrett repaid the money in full. Did Barrett know that the pyramid format was illegal in Illinois, and concocted the scheme anyway? Or was this an unknowing misstep amid an honest attempt to enrich a marginalized community? Solid answers remain out of reach, although Barrett has always spoken openly about the events and maintained his innocence. What’s evident are the polemics that emerged as powerful white men litigated a self-made Black leader in the court of public opinion. Here, the line between saint and sinner was fluid.

Amid the media scrutiny, Barrett continued his youth-focused outreach. In the spring of 1990, he raised funds to help send the Chicago Public School’s All-City Elementary Youth Chorus to perform at a concert at Carnegie Hall. “It has nothing to do with that [restitution],” Barrett told a Tribune reporter. “It’s just that I’m a pastor. I’m concerned about these kids going to New York.” And with the help of a local automotive dealer, Barrett also created an incentive program for students at Wendell Philips and DuSable high schools, giving away a new car to the valedictorian of each graduating class. “I wanted to encourage young people to stay in the picture,” he said. In a profound act of forgiveness, Barrett’s congregation stuck by him. It’s a core principle of Christian doctrine, but also a physical extension of the indiscriminate presence of God’s mercy, according to scripture. Today, Barrett still leads the Life Center COGIC (Church of God in Christ) on the South Side. The Prayer Palace—as the church is colloquially known—sits at 5500 S. Indiana Avenue, a stone’s throw from Barrett’s 20-block walk of reflection at age 16.

Throughout the 1970s, his choir’s young voices and breakout soloists blended with serious instrumentalists for a sense of fun as much as devotion. Barrett not only connected his church musicians with some of Chicago’s top session players, but the pastor also helped forge valuable connections among political shakers—even alongside partisan archrivals—and Afrocentric activists. Barrett’s identity and the sound of his choir stood out while his city provided collaborators and platforms. Along the way he touched the lives of countless youth. “I was an anomaly bordering on an enigma, I was very difficult,” Barrett said. “But my music reached me. So I thought that this will probably reach other young people who are trying to find their way.” He translated that journey into his biggest hit. “Just like a ship/Without a sail/But I’m not worried because I know/I know we can shake it/I know we can take it,” he sings on the title track of his lauded 1971 debut. “Despite it all, I was always positive,” he said. With an unwavering faith, and community focus, Barrett left an indelible mark on the South Side, and on the tradition of gospel music.

II. Walk Through The Valley: The Ascent Of Pastor T.L. Barrett

Thomas Lee Barrett, Jr. was born in Queens, New York, in 1944. His family moved to Chicago eight years later to assist Barrett’s aunt in building a church on the South Side. For the young Barrett, the Pentecostal churches he attended were filled with the expressions that are foundational to gospel music. Their vibrant musical repertoire and exultation in receiving the Holy Spirit were intoxicating, though the Pentecostal doctrine traditionally calls for abstemious behavior.

Barrett’s father was a loving guidepost who even looked after his son’s speech when he was hanging out in the streets in Bronzeville, their South Side neighborhood. “I would use the syntax of the neighborhood. I’d say, ‘This dude...’” Barrett explained. His father’s response to his son’s slang? “‘What is a dude? If you’re talking about a person, you say this person.’ And that’s why I was known as the L7 [square] of the group on the street.”

Such fatherly advice also shaped Barrett’s spoken discourse later on, especially his sharp intonation in his recorded sermons. But it did not translate to scholastic ambition. Considered an incorrigible student, Barrett disdained homework, was inattentive, and disrupted his classmates. After he was expelled from Wendell Phillips Academy High School, his father passed away unexpectedly, leaving Barrett with a choice: become a statistic or educate himself.

After burying his father on October 24, 1961, Barrett drove through the night and arrived at an uncle’s house in Queens, New York unannounced. During his stay, he enrolled in the school of life by working odd jobs (removing pituitary glands in a hospital morgue, shining shoes), earned his high school equivalency degree, and attended seminary at the Bethel Bible Institute in Queens. As a budding fan of jazz and gospel pianists, he took lessons from composer Irwin Stahl that complemented his self-guided learning. But another New York encounter proved more crucial: He met the famous Detroit-based Baptist minister and civil rights activist C.L. Franklin, father of legendary soul and gospel singer Aretha Franklin. As it turned out, C.L. was a distant cousin, who’d grown up not far from Barrett’s father near Mound Bayou, Mississippi.

“C.L. was a great influence on my life and my preaching style,” Barrett said. “He was considered the world’s greatest preacher, [the] most emulated and imitated preacher in the history of Black preaching. I was blessed to meet him when he was preaching in New York and I was playing piano for one of the groups. I approached him and told him who my father was and that my father said, ‘If I met you, I should tell you who I am.’ So we developed a relationship.” The humor and rhythmic delivery of Barrett’s spoken-word albums, recorded years later, recall those of the elder minister.

In 1967, Barrett returned to Chicago and became pastor of the Mt. Zion Baptist Church, located (as his debut LP would proclaim) at “5512 S. Lafayette Avenue, Chicago, Illinois, 60617 • 288-8020.” Barrett later developed Mt. Zion Baptist into the Church Of Universal Awareness as he became interested Christianity’s so-called New Thought philosophy, which emphasizes the everywhereness of God in the present, as opposed to preparing for a future return. Reverend Jesse L. Jackson Sr., who was national director of Operation Breadbasket, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s economic arm (who later formed Operation PUSH), would cross paths with Barrett several times in the ensuing decades, as each engaged with Chicago’s political, religious, corporate and artistic arenas. Jackson represented one of the country’s mighty civil rights organizations and the established Baptist churches, while Barrett built his platform from a smaller, far less centralized ministry. As Jackson became a national television pundit, Barrett focused on his music, congregation and city. Though diverging in scope, they shared a fundamental mission: to advance the Black community.

With key Chicago gospel stars passing on or struggling with poor health, younger parishioners stepped up, visualizing modern tunes outside the 1930s-era Thomas A. Dorsey songbook. A newer sound, referred to as contemporary gospel, began to emerge. Its star soloists tended to hail from Detroit or the coasts, and its melodies related to pop music as much as to the blues-based tradition. Choirs arose and conservatory-trained accompanists and arrangers shifted focus away from smaller groups. Fresh gospel musicians looked also to the soulful sounds spilling out of the radio for inspiration. While some saw these changes in gospel as divisive, Barrett embraced it all.

He connected with the city’s faith-based and broader musical communities, befriending a range of musicians. Saxophonist Gene Barge, a house player and arranger at Chess Records, who was pivotal in both R&B and gospel, would help shape Barrett’s earliest recordings, drawing upon his secular studio know-how and faith-based work leading The SCLC Operation Breadbasket Orchestra and Choir, which was the musical arm of the Jackson-led economic outreach organization. Barge worked on two key Operation Breadbasket albums as an arranger, producer or supervisor in the late 1960s: The Last Request and On The Case, both on Chess. Each fused classic gospel songs with new-school arrangements played by Chicago jazz and R&B legends like guitarist Phil Upchurch, pianist and iconic solo artist Donny Hathaway, drummers Morris Jennings and Terry Thompson, and others. The format Barge in-part created, as well as some of the personnel, would help shape the sound of Barrett’s recordings. But there was one key difference between Barrett’s work and the Operation Breadbasket LPs: The pastor’s albums featured distinctive, original compositions.

III. It’s Me O Lord: Like A Ship...(Without A Sail)

Barrett enlisted Barge to help produce his debut Like A Ship...(Without A Sail) in 1971, and the studio veteran brought in a few ace personnel. Upchurch, who’d just played on Muddy Waters’s Electric Mud and Fathers and Sons, Hathaway’s Everything is Everything, Minnie Ripperton’s Come to my Garden and Curtis Mayfield’s lauded self-titled debut, helmed guitar on four tracks, including “Ever Since,” a jubilant, heartfelt testimony if ever there was one. Richard Evans, the legendary Cadet Records arranger who worked with Ramsey Lewis, Dorothy Ashby and many others, played bass on the title track, at once anchoring and propelling its infectious groove. The combination of major R&B instrumentalists and choirs had become a nationwide movement, including New York’s more secular The Voices of East Harlem, who had the support of numerous political and music industry figures. But no big entrepreneur hired these players to work on Like A Ship. They did it out of their belief in 27-year-old Barrett. “He was a friend of mine, I just liked his talent,” Barge told music journalist Peter Margasak in 2010. “I tried to help pull it together and get a decent rhythm section sound.”

One similarity between Like A Ship and albums like The Voices of East Harlem’s Right On Be Free is a combination of youth and experience. Among the icons, seventeen-year-old Gary “Snake” Riley (occasionally misidentified as Gary Jones) features on Like A Ship, supplying remarkably developed piano and organ throughout. Fifty years later, Riley still collaborates with Barrett. “I’ve never seen anybody who could preach like him or be him,” Riley said of Barrett. “I was amazed and he could play the piano, that’s what really turned me on about him. He was just unique. More musically, because I was a musician, but he could preach and that was another thing that stirred me. A lot of preachers were just saying what they did last week. He never preached the same sermon. I still love him to this day.”

Riley’s serpentine nickname hinted at his sly approach to keyboards. He would switch up his right and left hands depending on how he wanted to emphasize his chords or bass lines, before anyone could see what he was doing. “The organ was on the floor where the pews were,” Riley said. “Musicians would sit in that section where I was and my style of playing was different, so they’d come, pen and paper, try to write down chords and they never could get it because my fingers moved too fast. They said I was like a snake.”

During the sessions, the church musicians had little contact with the studio players outside of the affordable Sound Market Recording studio at 664 N. Michigan Ave., where their album was recorded. Barrett and Riley said that the veteran instrumentalists were respectful toward the minister and his young crew, even with their different levels of experience. Like A Ship showcases Barrett’s compositions and asserts his confidence in this assemblage of personalities. Even within the bleak world he presents in the historic “Nobody Knows,” salvation offers an alternative while his repeated piano motifs signal upward movement.

The Youth For Christ Choir and lead voices Barrett, Phebe Hines and Loretta Lake provide kinetic energy while showing it’s the group effort, not the soloist, that is the star. On the traditional hymn “It’s Me O Lord,” both Hines and the choir build intensity through dynamic shifts on recurring phrases. While Lake swoops into the empty spaces the choir lends her on “Joyful Noise,” the song’s heavy accents declare that this is rock ’n’ roll in the best sense of the term. Riley blends in with the guests as they deliver a relentless tempo on “Ever Since.” But while some of these R&B inflections point toward the contemporary sound of James Cleveland, Barrett’s piano on “Wonderful” and the instrumental “Blessed Quietness” echoes such gospel musicians as Geraldine Gay, whose tone and improvisational flourishes resembled jazz pianist Erroll Garner’s early ’50s records. Barrett’s lyrics on the title track look back to his teen years and urge youths to remain steadfast. Empowerment through faith and community is the key.

“‘Like A Ship’ was written out of the pathos that is developed from growing up, being Black in America and having been put out of all of the grammar schools that I went to,” Barrett said. “I was subsequently dismissed from the high school that I went to and was told that I would never amount to anything. So I felt like a ship without a sail, but had I always had this positive subconscious mindset that I would make it. That’s when I wrote that song.”

In keeping with this model of self-assurance, Barrett released the album on his own Mt. Zion Gospel Productions label. This entrepreneurial drive was also part of the tradition, as several gospel artists had issued their own 45s and LPs. Many also owned their own publishing, since the time of Thomas A. Dorsey. The freedom that comes with self-ownership had proven crucial. But a big part of what makes Like A Ship stand out is that its collaboration between artists representing different genres lent it a sound that is bigger and brighter than such a bootstrap production might have indicated.

About two years later, in 1973, Barrett released Vol II: Do Not Pass Me By, his follow-up to Like a Ship. The album employs the same do-it-yourself aesthetic and self-released ethos (this time on the one-off Universal Awareness label). Here, Barrett and his group render a futuristic vision of gospel that is, by turns, mysterious and ebullient. On “O Sinner,” the eerie minor-key tone of the choir contrasts with the lead singer’s high notes. Tempo and mood shifts comprise “Here I Am” and its overall charging motion makes everything fit as a whole, while vocals and slightly bluesy piano are devotional yet stark on “Jesus Is All The World To Me.” The tension between the lead and choir on “Jesus, Lover Of My Soul” gets broken by a guitar line that might’ve sounded at home on a Norman Whitfield psychedelic soul production. Then, Larry Ball’s bass lines push the group forward through the choir’s precise delivery on “No Not One.” “There Is Only One” finds Barrett behind the electronic piano, squarely in homage to Stevie Wonder’s classic period, spurred by the popularity of 1972’s Talking Book.

Barrett and the choir play funk in even more vibrant colors on “I Shall Wear A Crown,” with the choir sounding onomatopoeia effects as they sing about trumpets. This was Barrett’s rearrangement of an older Pentecostal Church Of God In Christ (COGIC) song, and the line about praising the Lord with drums harkened toward the very real future in which full drum sets would be more prominent in COGIC services, such as those Barrett leads today. If Barrett and the Youth For Christ Choir sounded not too removed from their secular contemporaries, it was because they were reaching for the same audience. “We did jazz, we did the more contemporary gospel and got into the funk thing, too,” Ball said. “It was to promote the youth, bring them into the church, and, yes, it was successful.” While each album would become valued decades later as pinnacles within Chicago’s funky gospel soul sound, in the early 1970s they primarily served to set Barrett and the choir up for their next adventure.

IV. I Found The Answer: Barrett Signs On With Soul Powerhouse Stax Records

A year after the release of Like A Ship, the famed Memphis R&B label Stax launched its Gospel Truth Records imprint. Longtime home to soul hitmakers including Otis Redding and Isaac Hayes, Stax was finding its way through a period of transformation in the early ’70s. Al Bell, a Stax co-owner and its de facto leader in that era, had steered the label toward openly embracing Black consciousness, culminating in August 1972’s Wattstax festival in Los Angeles, in which the label’s artists performed in commemoration of the 1965 Watts Uprising. Gospel music’s historic and unmistakably African American identity was a big part of highlighting the company’s cultural mission. That the politically conscious Staples Singers—one of the label’s biggest crossover acts—remained devout only reinforced the fact that church music remained pivotal in the post-civil rights movement era.

Undoubtedly, Bell also saw the commercial pull of gospel soul combinations and he had made inroads within church audiences, especially via his association with Jesse Jackson. The Gospel Truth roster ranged from the young contemporary trio The Rance Allen Group to veteran minister Maceo Woods and the Christian Tabernacle Choir. Barrett described his own I Found The Answer LP, released in 1973 on Gospel Truth Records, as a “gap bridger” between generations, bringing Allen and other vocalists in to perform with his choir at downtown Chicago’s prestigious Orchestra Hall. Produced by Barrett, I Found The Answer highlighted his organization’s musical advancements and the pastor’s blending of new sounds and venerated traditions, as well as Stax’s new emphasis.

One of those developments was bassist-arranger Larry Ball’s arrival at Barrett’s Mt. Zion Baptist Church when he was about 22-years-old. His prior musical experiences set him apart from his peers. Considered a prodigy, Ball had begun working the clubs as part of his pianist brother Lewis Ball’s jazz trio while still a student at Bronzeville’s Dunbar Vocational High School. After playing bass behind saxophone legends Gene Ammons and Sonny Stitt, Larry Ball worked with contemporary gospel singer Jessy Dixon and toured as a part of Paul Simon’s early ’70s band. Then, upon Larry’s return to Chicago, Lewis introduced him to Barrett. “Pastor Barrett was, most of all, my friend, a mentor,” Larry Ball said. “I found him to be extremely wise and he had so much to offer. Basically, I didn’t want to do anything but stay in church and listen to his sermons. I learned so much. He’s a musical genius, the way he can just sit at the piano and create a song on the spot and I found that to be amazing.”

Despite Barrett’s inspiring spontaneity, Ball recalled that rehearsals leading to sessions for I Found The Answer were rigorous. “T.L. would really work the choir, especially when we had to record,” he said. With a bigger instrumental assemblage on the album, thorough prep work was required. Organist Gary “Snake” Riley remembers feeling excited about recording with horn players for the first time. The horn section on “I Don’t Know How Long (He’ll Wait For You)” responds to the statement in the song’s title with a strong and slow groove that would be familiar to listeners of Stax’s soul albums. And The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s horns and string sections weave in and out of the choir passages on “Shine On Me,” an arrangement that remains uncanny in gospel. Lewis Ball’s piano lead on “He Rose (From The Grave)” suggests the spirituals-to-jazz groove that his Chicago colleague Ramsey Lewis had popularized in the 1960s, with improvised vamp jams that rival his contemporaries’ sound in secular arenas.

Barrett uses not just R&B-inspired music to appeal to a young audience, but also hip language in the anti-drug, pro-faith message of “Turn On To Jesus,” with contrasting melodic pieces that fit together as Larry Ball’s bass line directs the choir’s ascent. On “I Came To Jesus,” somewhat dissonant violins blend with the horns above rapid cymbal hits (sounding similar to Willie Hall’s drumming on another Stax album, Isaac Hayes’s Shaft). Barrett also employs sly allusions to pop songs from the Top 40 radio airwaves of the era: He includes refrains from The Beatles’ “Something” in “What Would You Give” and from Carole King’s “You’ve Got A Friend” in “I Am So Glad.” In further reclaiming Aretha Franklin’s music for the church, “Pray, Pray, Pray” borrows a melody line from her 1967 hit “Chain of Fools.” I Found The Answer also embraced the contemporary gospel movement with “Trouble And Strife,” a sound that sometimes featured introspective piano-led ballads and soloists alongside the weight of a choir (examples include Jessy Dixon and Andrae Crouch). Barrett’s magnetic vocals tie everything together.

Despite Gospel Truth’s consistent quality and albums like I Found The Answer that might’ve appealed widely, it was a short-lived operation. According to Barrett, the record “caught some buzz but sales were mediocre.” Stax entered bankruptcy soon after its release and would close up shop at the end of 1975. Still, for the participants on I Found The Answer, the experience was as rewarding as the music has proved lasting. As Larry Ball said, “Gospel is something that becomes a part of you.”

V. Sowing Spiritual Oats: Barrett Thrives In Chicago Pulpit and Studios

Back in Chicago, Barrett flourished in the mid 1970s. After morphing Mt. Zion Baptist Church into Mt. Zion Church of Universal Awareness, he founded the Life Center Church of Universal Awareness in 1976. His message that God exists in everybody and everything, combined with his focused concern for life in the present, as opposed to a fixation on the afterlife, resonated in a troubled South Side neighborhood. Just a few blocks north of the church stood the imposing Robert Taylor Homes housing projects. These towers, built in the early 1960s, had crystallized the poverty and crime that resulted from the city’s racial segregation. Barrett believed all of it made his mission that much more crucial.

“I was feeling, I guess you could call it my spiritual oats, in wanting to build my own church and not willing to go to heaven from a church that somebody else built,” Barrett said. “So I told our people that we would build a Prayer Palace in the malice. Our location was considered the worst crime location in Chicago that year. And so I just told God, ‘While you’re blessing others to do great things, do not pass me by.’ So I want to build a church, too. I want to build a great mission, I want to rise from obscurity to prominence. All of that kind of thing. So that’s how that philosophical idea became flesh.”

Barrett’s positive message for the Robert Taylor Homes drew in more singers and musicians, as did his morning drive radio program, which he began on the popular WBMX in 1974. This new station on the FM dial targeted upwardly mobile African Americans with call letters that allegedly stood for “Black Man’s Experience.” With radio’s FM band broadcasts still novel for Chicago listeners, the station set out to compete against the older AM station, WVON, which had held sway in the city’s Black community for a decade or more. Young and hip, Pastor Barrett fit right into that initiative. Perhaps not so coincidentally, WBMX would sometimes broadcast Barrett’s show to run at the same time as the WVON weekday gospel program. All of this brought Barrett more attention from artists with Chicago backgrounds, including Hathaway and the members of Earth, Wind & Fire, who’d stop by his church and work with the choir. As pianist Reginald “Reggie” McEastland said, “It could go from being a service to being a jam session. We didn’t want to go home, we were having so much fun.”

“My music and ministry combined had generated that kind of interest in people” Barrett said. “I was able to become so close to Earth, Wind & Fire that when Philip Bailey’s mother passed, they flew me to Denver to do her funeral. When Maurice White’s mother passed, I did her funeral at Rockefeller Chapel [in Chicago]. I was on the radio and they would call me from all parts of the country, all parts of the world where they were touring. We remain close to this day.”

During these years, Barrett appeared alongside a range of established musicians as well as spiritual leaders, according to numerous reports in the Chicago Defender. He’d long orbited the same sun as The Staple Singers on the live gospel circuit. Barrett performed at Perv’s House—the lush South Side nightclub founded by Roebuck “Pops” Staples’ son Pervis after he left the family band in 1969—as a benefit for his mentoring program in the Robert Taylor Homes. He also collaborated with Chicago avant-garde jazz icon Phil Cohran at a 1975 multimedia event called Destination Mind Explosion. Cohran’s influence on all corners of the South Side’s cultural and artistic heritage cannot be overstated. A former member of the Sun Ra Arkestra who co-founded the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), Cohran formed the hypnotic Artistic Heritage Ensemble and ran Chicago’s Affro-Arts Theater in the late 1960s, merging spiritual jazz and gospel music with Afrocentric thought.

Cohran influenced legions of Black Chicagoan performers and activists, and Barrett found a kinship with his artistry and philosophy, which came through in his own recordings. “He was in the vanguard of social change, he was totally pro Black, pro-Afrocentric,” Barrett said. “He was attracted to my music and I was attracted to the fact that he dared to be different. We collaborated as much as we could, and worked together as much as we could to inspire our people.” In the midst of all of this, Barrett released his second album under the name Do Not Pass Me By, this time on the Miami-based Gospel Roots label.

VI. Do Not Pass Me By: New Musicians Elevate Youth For Christ Choir

A few months before the recording of the second Do Not Pass Me By album, pianist Reginald “Reggie” McEastland joined up with Barrett, in the spring of 1975. While playing keyboards in rock bands around town, he’d learned of Mt. Zion’s musical reputation from friends within the church. McEastland recalled that the sessions took place in Chicago at Paul Serrano’s P.S. Recording Studios on 323 E. 23rd Street; he also described musical supervisor Ralph Bass, a veteran Chess producer, as, “an energetic little guy who knew what he wanted and didn’t know how to tell you. After I pursued him, I got more of an understanding out of him and it became clear.”

With Do Not Pass Me By, Barrett and his congregation took a wider embrace of early gospel, while also looking to where the music would go in the future. The title track reworks Fanny Crosby’s 19th century hymn, “Pass Me Not, O Gentle Savior,” lending it more rhythmic heft. “After The Rain,” on the other hand, sounds like it could light up the dance floor as much as the pews. The initial riff was Gary “Snake” Riley’s. “I was playing the piano, just playing music and wasn’t trying to write a song,” Riley said. “At this particular time, I was playing the beat, playing it all the way through. Pastor Barrett went upstairs, came downstairs and said, ‘I like that, what’s the name? I said, ‘I don’t know.’ He was just an on-the-spot person, he could just do stuff. He said, ‘Play your melody, I’m going to sing this.’ He made some changes. When the youth rehearsed it, they killed it, they tore the song up.”

Barrett’s lyrics came to him while watching the sun shine after a deluge, when he was thinking about his own determination to create unconventional church music. “When I sat down at the piano, I thought about that line, ‘And after rain, after pain,’” Barrett said. “‘Don’t you give up until the day is done. There’s only one who brings the sun.’ Many wouldn’t play my music, they said it wasn’t traditional but they didn’t log it as gospel. And nobody in the secular world would want to give it a listen if it was branded as gospel. So I just wrote what I felt.”

Barrett added synthesizers to complement the piano and organ. The oblique keyboard lines that guide that track came from longtime Chicago soul arranger Thomas “Tom Tom” Washington, according to Riley. This was a few years before groups like The Winans made the electronic instrument prevalent among gospel artists in the 1980s. Synthesizer also features on newest member McEastland’s standout arrangement of the traditional hymn “Father I Stretch My Hands to Thee,” shortened to “Father I Stretch My Hands” on the album. “He’s such an expert musician and singer,” Barrett said of McEastland’s work on the song.

McEastland, who is blind, takes the lead. His dynamic singing—including a gut-rattling falsetto—is alternately hushed and mighty, driven by the power of perseverance. His voice rises against the soulful backing of the choir, like fire meeting the wind, as the song journeys past the seven-minute mark. “He’s saying that I stretch my hands to thee, because I really can’t see,” Barrett explained. “He sang it with such soulful involvement that we were all so moved.”

Barrett picks up the lead on “I Want To Be In Love” and while the lyrics reflect a divine yearning, the melody line has a more earthen, pop-minded quality. The bridge was even derived from The Beatles’ “Hey Jude.” As his answer to the God Is Dead Movement (the cover story of an April 1966 issue of Time magazine), Barrett wrote “These Are The Words.” Along with its response to an ongoing theological and philosophical issue, the music conveys the chord changes in contemporary gospel while the bass adds a countermelody. On the older church song “So Many Years,” Barrett let young vocalist Vickie Bowden take the lead. Even after diligent choir rehearsals, she felt underprepared but also compelled—and by more than just her pastor’s encouragement.

“The person who led wasn’t there and Pastor Barrett said, ‘Vickie, I think you can lead this song,’” Bowden said. “I was timid, very shy, walked up like a little mouse and went OK. And voilà, that was on one take. I have no idea why, maybe it was divine intervention. I don’t know how he knew I could sing that song. I had no experience singing it, I hadn’t even rehearsed the song.”

One of Barrett’s favorite compositions, “You May Not Need Him (Til Tomorrow),” stemmed from his beginnings as a traveling evangelist, before he’d been ordained. The lyrics are about choosing a higher power to face life’s uncertainties, and its musical framework accentuates that point. “When we go into the mixolydian mode, it’s not a common chord structure,” Barrett said. “I haven’t any formal musical training, I just know that it helped get the soulful intent of that message across.”

After Do Not Pass Me By, Barrett and his church weathered more changes. Larry Ball left Chicago in 1976 to become conductor of The Wiz on Broadway, before embarking on a career that featured service as Smokey Robinson’s bassist and arranger. Meanwhile, Barrett and the Youth For Christ Choir continued recording 45s into the early 1980s. Some were lighthearted, like the groove that the group puts on “Jingle Bells,” which bears a resemblance to Donny Hathaway’s “The Ghetto.” As Barrett said, that was one way he wanted to keep young people involved in the church’s music making.

VII. Of Scripture and Soft Drinks: Barrett’s Sermons Carry On a Rhetorical Tradition

Before Barrett released his visionary take on gospel music, he tracked his charismatic sermons to reel-to-reel tapes in front of his congregants, and issued these recordings as albums from the late 1960s into the mid 1970s. “What Is a Christian” was released in 1968 and marked Barrett’s very first recording. C.L. Franklin’s influence was on full display, in the way Barrett’s syllables are stretched and in how he times his drops and pauses with practiced expertise. His rhythmic elements do as much work as his verbal content. These albums also marked a continuation of a tradition of African American recorded sermons, one locus of which was Chicago. In the early part of the 20th Century, preachers recorded sermons at Paramount’s rented studios in downtown Chicago on the same day as blues singer Ma Rainey. Back then, Reverend James M. Gates spoke in a folksy dialect to take on such social issues as racism and bigotry. Fifty years later, Barrett’s sermons expanded on these themes, using similar rhetoric. But Barrett also used the marketplace to address struggles that would have been visible to anyone who lived in his communities during the 1970s. Sometimes that meant watching television commercials.

The sermon marketed as “Hawaiian Punch” exemplifies the Barrett wit, utilizing a cartoon ad for a soft drink combined with a biblical parable as a way to delve into deeper truisms. Pastor Barrett’s overarching message is that anyone can fall victim to scams in a market economy. His predecessors would have understood how he used dialect to express his message. “One of the greatest ideas that man ever came up with was when he put [cherry] flavor to medicine,” Barrett said. “[Those] additives made it more palatable, more enjoyable. So you got the medicine you needed but it didn’t shock your system. That’s how I feel about humor. The word is very, very important but it doesn’t have to be so shocking, hard, stentorian. So people can laugh while they’re being healed.”

On the flip side, Barrett continues the Black Church’s tradition of political participation. He strongly urges parishioners to register to vote while also monitoring politicians’ inclinations to deceive. “It’s called taking responsibility for your own viability,” Barrett explained. Yet Barrett did more than just advise his congregation. He made his church a platform for local candidates, including foes representing sometimes opposing constituencies during the 1970s and early ’80s. While his church warmly welcomed Harold Washington during his successful campaign to become Chicago’s first Black mayor in 1983, Barrett told them he would provide similar courtesies to Washington’s incumbent opponent, Jane Byrne. Years later, through victories and defeats, his dedication to the electoral process remained resolute.

“This is how I feel about voting: I told my congregation that if you are physically able to vote, and you choose not to, I would prefer you join another church,” Barrett said. “I would not even be proud to call you a member of my church. If you don’t vote, please don’t tell anybody that you’re a friend of mine. Too many people have died, their blood was shed for us to have the right to vote. I will not be one of those who is guilty of their dying and suffering in vain.”

On “John Smyth” (named in reference to a Chicago furniture chain), Barrett returns to commercials as metaphors, to advocate shared principles of universal truth while also maintaining one’s individuality. The more serious “Dry Bones” uses the biblical story of ancient Israel’s revival to call on African Americans to take care of themselves, advocating for self-improvement over sloganeering. Overall, Barrett was working in response to the tragedies that were ongoing in his hometown. The first half of the 1970s marked an alarming rise in Chicago’s homicide rates, which were exacerbated by segregation, job losses, and gang wars tearing apart established social networks. As the Chicago Tribune reported, 1974 was the deadliest year for homicides—970 in the city, by their count. From his outreach efforts at the Robert Taylor Homes, Barrett knew the situation all too well.

For some of his sermon albums, Barrett got national distribution through Randy’s Records of Gallatin, Tennessee. Proprietor Randy Wood, who founded the Dot Records label in Tennessee in the 1950s, and oversaw its move and sale in Hollywood, had been the largest mail-order record distributor in the country, according to the Portland Sun, his hometown rag. Wood issued Barrett’s “If I Should Wake Before I Die” and “It Tastes So Good” LPs under his Randy’s Spiritual Record Co. imprint, which released the sermons and gospel music of Black Churches and ministers throughout Middle America. Barrett’s 1977 sermon LP “Roots” was issued through Gospel Roots—same as the second Do Not Pass Me By–and distributed through founder Henry Stone’s T.K. Records. The album’s Afrocentric cover art and theme highlight how much Barrett gained from Phil Cohran. Despite such efforts, these LPs were still sold primarily at public appearances. But that fact failed to diminish Barrett’s outreach over time. Getting the message out mattered more to Barrett than sales figures, anyway.

VIII. Voice Of The Elder: Pastor Barrett’s Music is Resurrected

Barrett issued his last recording in 1984. The 12-inch single interpreting “My Country Tis of Thee,” arranged by Gary Riley, whose organ parts are complemented with synthesizers, is backed with a lively rendition of the traditional “In the Old Time Way.” “We believe in being patriotic to our country even though this is not our motherland,” Barrett explained. “We call it the other motherland.” He added that neighborhood outreach and growing his congregation at the Prayer Palace on Indiana Avenue began to take precedence over his recordings. “Our ministry moved into another strata,” he said.

As the 2000s dawned, Barrett found himself an elder statesman in the city’s gospel lineage, as well as within the COGIC denomination. He had long since exchanged the sharp suits he wore in the 1970s for West African-inspired robes and kufi caps. In further cross-continental connections, he received honorary doctorates from Monrovia College in Liberia. At the 2006 Chicago Gospel Festival at Chicago’s Millennium Park, Barrett took part in a headlining tribute to influential composer and choir director James Cleveland. He also officiated at pianist Geraldine Gay’s 2010 funeral at her brother Donald Gay’s Prayer Center COGIC.

The records Barrett made in the 1970s are now heard in ways he could not have imagined. “Father I Stretch My Hands” was sampled by Chicago native Kanye West on his 2016 album The Life of Pablo. Infused in two tracks on West’s critically-acclaimed work, “Father Stretch My Hands Pt. 1” and “Father Stretch My Hands Pt. 2,” the uses prompted widespread attention and additional samples of Barrett’s catalog by pop producer DJ Khaled (“Nobody”), rapper T.I. (“Black Man”), electronic duo The Knocks (“All About You”), and many others. Barrett’s music has also appeared in films, television shows, and the kinds of commercials he used to sermonize on. These productions have earned Barrett widespread media attention, and he emphasizes that it crosses cultural as well as religious lines. “I just got a letter from a Muslim in Kentucky,” Barrett said. “He received music from a rap group that includes my music. So I’m very grateful, very thankful to God that it may be late, but it’s great to have people interested today in music that I wrote 40 years ago.”

The surrounding neighborhoods of Barrett’s 1970s stomping grounds have experienced big transformations in the intervening years, some of which he envisioned back when he was recording. The nearby University of Chicago had long considered his part of the South Side as burdensome at best, but has made significant moves to buy up property in the area with promises of revitalization. The imposing Robert Taylor Homes were demolished in 2007. The ornate white brick and stained glass facades of the Life Center COGIC church dominate its intersection near 55th & Indiana. Just feet from its doors, Barrett’s name adorns the brown street sign that designates Garfield Avenue in his honor. Inside, bassist Wayne Barrett and his drummer brother Dwayne Barrett, although of no blood relation to T.L., have been his longtime musical directors. They’ve worked continuously on original music, with Gary “Snake” Riley still at the organ. The groove and the spirit are still here.

In 1981, Barrett was inducted into the Wendell Phillips Academy High School Hall of Fame—the same high school that kicked him out as a boy—for his dedicated community outreach and positive influence throughout the South Side. Today, a photo of Barrett lines the halls alongside other notable alumni such as Nat King Cole, Sam Cooke and fellow drop-out Dinah Washington. “It was a bonafide ceremony,” he remembered. “They did an actual assembly for the induction.”

Reflecting on his life, Barrett expressed gratitude for the longevity of his ministry. And though he appreciates the renewed interest in his music, he hopes to be remembered for a far more uncomplicated, though no less important, characteristic—one deeply rooted in the church’s foundation and his father’s guidance when he was a boy. “I teach my people not to strive to be the biggest or the best or greatest church, but to be the nicest church,” he said. “Because no matter what else you are, it really doesn’t touch the heart of anybody if you’re not nice. There’s something about the cosmology of us all where only something that comes from the heart can reach the heart. So if I can influence people to be nice to each other, then I will have been successful.”

-Aaron Cohen, April 2021