The tourist in Freeport, Grand Bahama is a creature starved for information. Street names are irrelevant to locals, appearing only on inconsistent road signs and the hard-to-find maps. Distant nameless hotels reveal themselves to be desolate, storm-ravaged ruins upon close approach. Bus routes are secrets known only to bus drivers themselves. But the attentive tourist begins to notice a single exotic word creeping into view from soda cans and souvenir shops. That word is goombay, and goombay means everything to Bahamian musical culture.

Goombay is a drum. Goombay is an annual Bahamian street festival. Goombay is a flavor, literally, and not entirely distant from pina colada. And goombay is the genre of Bahamian music given its name by the drum that beats its rhythm. But goombay is also a sort of shorthand for what native Bahamian musicians of the 1970s crafted: an island music instantly familiar and specifically Caribbean, yet unequivocally Bahamian.

“Stay in the bush!” That’s how Frank Penn quotes his much younger self, a man of incalculable importance to the music of Grand Bahama Island in the late 1960s and early 1970s. In that era, Miami broadcasters and American business interests had imbued the island with a cultural identity somewhat more Floridian/Caribbean than Bahamian. Penn’s slogan was guidance to a broad range of talents he recorded and promoted from GBI, his low-slung modest white stucco studio and label headquarters near the harbor on Freeport’s Queens Highway. The bush meant Grand Bahama Island; the slogan a demand that GBI’s sonic export have a Bahamian undercurrent, however strong its Stateside influences might be. From this cultural battleground emerged a sound that bodysurfed both sides of the Straits of Florida.

Barely inhabited until 1955, Grand Bahama saw a population explosion in the early 1960s after Edward St. George began developing the island’s West End as a tourist destination. Caught in the middle of this burst was Frank Penn, a recently divorced barber/bartender seeking refuge from his native Nassau’s noise and overcrowding. Perhaps overestimating Grand Bahama’s need for haircuts, Penn eventually turned to his third trade and went to work as a carpenter for Freeport developer Guy Protano.

The fruits of his labor would become the Bamboo East nightclub. At the venue’s 1962 completion, Protano, bound for the States, entrusted the room to Penn the bartender. Noticing a dearth of clubs for the island’s burgeoning local youth culture, Penn turned away from West End and in the process transformed the Bamboo East into Freeport’s premier spot for live music and dancing. Unknowingly, Penn had laid the foundation for an entirely different explosion.

As Penn cultivated grassroots in Freeport, Jay Mitchell was going in the opposite direction; since his Grand Bahama youth he’d dreamt of leaving the breezy isle for Nassau’s urban fervor. Raised in the Eight Mile Rock settlement, Mitchell was a natural star in both the church where he sang in the choir and as a dancer for his godfather’s band. He picked up the guitar, the maracas, the organ, and any instrument he could get his hands on, mastering each to a high level of proficiency. At the tender age of eleven, he was sneaking out of the house to perform, receiving beatings from his grandmother upon his return in the wee hours of the morning, pockets brimming with tourist cash. In 1963 he cut his first record, “I Need You,” with the Singing Vibrations, a group he assembled from church. With the taste in his mouth, the sixteen-year-old Mitchell set off for Nassau. A try out to sing lead for a band with a steady gig at the popular Imperial Hotel would create a rivalry that would propel his entire career forward.

The last person Mitchell expected to encounter at the Imperial rehearsal was Leroy “Smokey 007” McKenzie, his cousin. The characteristic laziness of lead vocalists had caused the band to hire two singers, assuming that at least one would not show. They both swallowed hard and split a paycheck, but the friction created that day would go on to energize the local scene, a scene ever threatened by stagnation from the “safe,” tourism-supported performances that dominated Nassau. During the late 1960s, at the height of their respective powers, Mitchell and Smokey 007 were like leaders of competing gangs, with loyal followers often trying to undermine the rival’s performances. They contended at everything: clothes, wealth, showmanship, success. While Smokey 007 was a more charismatic performer, Mitchell was the superior songwriter, producer, and musician. His audacity, however, was unrivaled. Mitchell’s big break came during a Chuck Jackson concert: he jumped on stage mid-lyric, grabbed the microphone from Jackson’s hand, and finished the number to the delight of the entire crowd. The show’s promoter, watching from sidelines, tendered him a management contract within the week.

The very connected Father Allen wasted no time, and together the two set off to make Mitchell the undisputed greatest Bahamian performer. A slot on an all-star tour of the United States was quickly secured, and Mitchell would spend the next few months bringing the Bahamas to the audiences of Aretha Franklin and Otis Redding. When the curtain went down he fell in with Franklin’s guitar player Jerry Weaver and Redding, learning dozens of lesser-known R&B songs for a proposed Redding produced album for Atlantic. But instead of the story ending with Redding’s plane going down, it was Mitchell who crashed. Homesick and worn out by the always-on nature of road life, he quit the tour and retreated to his modest Freeport existence. Back in the safety of Grand Bahama, Mitchell and his band the Mitchellites would cut an album heavily steeped in the sounds of the tour, but with subtle flourishes from his native land. “I Am The Man For You Baby” is the perfect synthesis of these two worlds, finding Mitchell coyly explaining himself as “just a young Bahamian boy,” perhaps as a nod to his Stateside comrades. In 1972 he would take this fusion further on the LP Souvenir of Freeport Bahamas, an album of Mitchell-fied “covers” issued by the Bahamian Ministry of Tourism. “Mustang Sally” and “Tighter & Tighter” are mere shells of their original forms, as Mitchell & Co. transform their radio-ready hooks into impossibly long funk workouts for the undiscerning poolside listener. For the few that managed to pick up the souvenir, it was a fitting reminder of Freeport’s left-of-center take on R&R.

Though Jay Mitchell and Frank Penn were on different tracks sonically, both were establishing impressive careers as the Bahamas moved toward independence. From 1968 to 1973, Penn had managed to release three albums recorded at Miami’s Criteria Studios; the third would be his crowning achievement. Backed by the Esquires LTD, At Independence was Penn’s first true stab at straddling the strait.

Inexplicably, the band’s vocalist, Arthur Rollins Jr., pokes his head in the studio for a little over a minute to deliver a fairly uninspired take on “Theme From Shaft,” but brothers Donny and “Kinky” Fox make up for it in spades with their unrelenting B3 and high hat attack. Guitarist Wilbur Fawkes leans heavily on his wah for the quirky civil rights anthem “Gimme Some Skin,” which ended up being the album’s only single. All three albums and the spawned single were released on the aptly named Penn’s label, but the costly trips to Miami to record inhibited the label’s ability to grow. Seeing a gigantic hole in the marketplace, Penn approached the Bunting Company, an American film concern that held the island’s only recording license, about opening a dedicated recording studio in Freeport. Success came immediately; every hotel band and island crooner stopped in to record a demo, giving Penn a talent pool to pick and choose from for future releases.

Inexplicably, the band’s vocalist, Arthur Rollins Jr., pokes his head in the studio for a little over a minute to deliver a fairly uninspired take on “Theme From Shaft,” but brothers Donny and “Kinky” Fox make up for it in spades with their unrelenting B3 and high hat attack. Guitarist Wilbur Fawkes leans heavily on his wah for the quirky civil rights anthem “Gimme Some Skin,” which ended up being the album’s only single. All three albums and the spawned single were released on the aptly named Penn’s label, but the costly trips to Miami to record inhibited the label’s ability to grow. Seeing a gigantic hole in the marketplace, Penn approached the Bunting Company, an American film concern that held the island’s only recording license, about opening a dedicated recording studio in Freeport. Success came immediately; every hotel band and island crooner stopped in to record a demo, giving Penn a talent pool to pick and choose from for future releases.

The Bahamas declared their independence on July 10th 1973, and those tumultuous early years of nationhood catalyzed a flowering of creative development. Adding to the excitement that social change brought was a contest to pen an anthem for the Bahamas; thousands of citizens submitted entries. This outpouring of songwriting brought the cause of music by and for the Bahamian people to the forefront of national concern. Before this point, very few artists on Grand Bahama, other than Frank Penn and Jay Mitchell, strove to become more than just hotel bands. Artists like Cyril “Dry Bread” Ferguson and groups like Willpower, T-Connection, and Foxfire emerged around the advent of independence. They embodied a “new guard” of Bahamian artists, with Penn and Mitchell as their patriarchs. When Bunting returned to the United States in 1975, he handed Penn the mortgage on his studio property. With the debt firmly in his possession, Penn consolidated the studio and label under one name: GBI Recording Co.

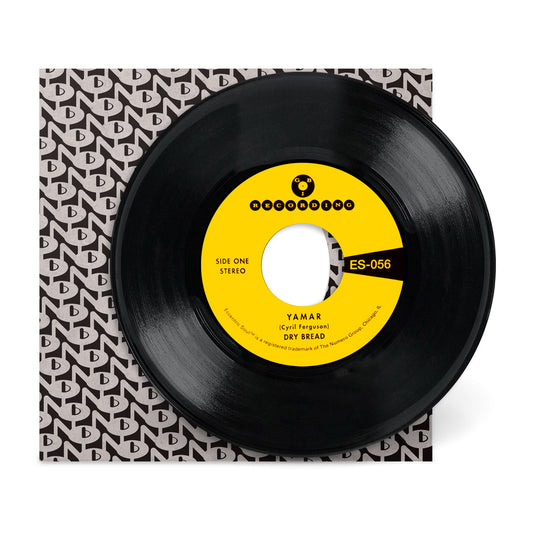

Cyril “Dry Bread” Ferguson, guitarist and native of Crooked Island, owes his nickname to his voracious appetite and his own humble beginnings. His work for GBI stemmed from an award he received from Frank Penn: Most Potential Artist at the inaugural Music Maker of the Year Awards in1972, a tradition Penn began in hopes of further invigorating public interest in Grand Bahama artists. Stunned by Ferguson’s performance of his original composition “Yamar,” Penn invited him to GBI to cut a record. The flip, “Words To My Song” is a tongue-tied prediction of writer’s block, created on the spot and inspired by drummer Ebo’s flawless skin wizardry.

“Gonna Build A Nation,” his plea for civic understanding and perseverance, was recorded two years into independence and immediately banned from ZNS, the state controlled radio station, for being too “cynical.”

Founded by Gladstone McEwan in 1974, Willpower’s combination of rock and funk with an island idiom was a fixture in both the West End and Freeport throughout the mid-70s. McEwan, a Nassau native, had backed Jay Mitchell, Smokey 007 and the legendary Andre Toussaint before puddle-jumping over to Freeport and finding refuge at GBI.

While their first single, “Say What You Like,” was a #1 hit, it’s on the acid-rock flip to the follow up, “People Won’t Change,” that the group really hit their stride. Willpower eventually expanded to six members and continued to record throughout the decade, but none of their later recordings captured the intensity of their GBI output.

Ozzie Hall was another island hopper who washed up on Grand Bahama and never left. A Kingston import, Hall had done time as Freddie Munnings’ alto saxophonist in Nassau before being offered a job at the prestigious Jaktar Resort in West End.

He gigged steadily with old timers Fred Callendar and Teddy Greads before eventually putting his own band together for a long run at the Grand Bahama Hotel. The Caribbeans, made up of Eddie Guignard on piano, Percy Roker on drums, Carl Knowles on bass, Herbert Miller on guitar, and King Turtle on drums, would back Hall for nearly 20 years, but content with a steady paycheck, the group never left the hotel. A Visit With Ozzie Hall is a fairly straightforward island lounge album but for one immediately ear pulling moment when the group tackles Paul Desmond’s “Take Five.”

Though never granted full membership in Freeport’s upstart scene, the Mustangs were one of the more prolific groups on the island. Primarily a hotel poolside band, they embraced Penn’s nationalist philosophy, incorporating indigenous Bahamian styles into their three heavily Jamaican influenced albums recorded between 1974 and 1978. “Whatcha Gonna Do ’Bout It” and “The Time For Loving Is Now” catch the group at their best, tipsy on Goombay Smash and sneaking tokes between choruses.

Sylvia Hall and the Gospel Chandeliers exemplify GBI’s kinship with a deeply religious Bahamian public. Both songs advocate for church virtues, one for abstinence, the other for truthfulness. “Don’t Touch That Thing” is a traditional Bahamian children’s circle rhyme served over a bed of blistering funk, while “Honesty Is The Best Policy” is nowhere near the gospel the group’s name implies. Both are more than likely custom jobs, though the Gospel Chandeliers’ massive line up of vocalists (Faye and Judy Bassett, Alice Penn, Paulette Rolle, Ceva Cooper, Ella Rolle, and Veronica Meadows) and musicians (Hayland Nottage, Joel Green, Harrison Wilson, Levitte “Pepsi” Forbes, and Howard Grant) did perform off and on.

In little over a year, Frank Penn had recorded every major and minor performer on the island but one.

Though he had booked Jay Mitchell into the Bamboo East regularly, it was a series of Penn-promoted smash revues at Freeport’s Kasbah Bar that inspired the two to collaborate on tape. Mitchell’s 1974 debut on GBI, Your Mama Your Daddy Again, found the two finally creating a perfect hybrid of Bahamian and American sounds. The jacket depicts traditional straw dolls sitting on an organ, a not-so-subtle symbol for the melding of vernacular and modern cultures. “Goombay Bump,” penned by Penn for Mitchell, continues on this tangent, mimicking the sounds and energy of the goombay and junkanoo street festivals with clamorous horns and a cardboard box trapped bass. Two years later they returned with Impartiality, a deeper and more personal record that Mitchell tracked at home but finished up at GBI.

The mysteriously psychedelic cover pays homage to Reiki, the Japanese life force energy treatment that Mitchell practiced. His longtime backing trio of Leslie Lewis, Vincent Dames, and Sherlin Woodside are in top form on “Funky Fever,” and Mitchell wastes no time calling them out individually. The album would be Penn and Mitchell’s last hurrah and possibly the creative zenith of GBI.

Time and weather haven’t been easy on GBI’s storied past. Bit by bit, priceless ephemera

has washed away like the Bahamian sand itself does daily. Who can say what Grand Bahama Goombay might’ve looked like ten years from today? So much is long lost: the Grand Bahama Hotel and much of West End is gone, the Bamboo East is just a bar, and the only record shop on the island traffics more in calling cards than music. Frank Penn’s meager photo collection documents as much tragic damage wreaked on GBI by Hurricanes Floyd, Frances, and Jeanne as it does the label’s precious mid-70s boom. The studio headquarters has reacted piously, refocusing its efforts toward godly TV production and doubling as one of Freeport’s leading religious gathering places. Across town, trophies and gold records decorate Jay Mitchell’s corner of the island, a studio anteroom covered—walls, ceiling, and all—in brown shag carpet. As for the locals, they know the story’s principals as well as trusted neighbors: ask anyone where Jay Mitchell lives and you’ll get directions to the place complete with landmarks. Wrought iron music gates front the entertainer’s Freeport home, modestly recalling a sort of Graceland in the bush. Their whimsical strength locks in a promise that the scattering and loss of classic GBI sound has finally found its end. You no longer have to be a Freeport tourist to know exactly what goombay means.