It’s fun to watch bodies move around. Since Philadelphia’s jubilant Bandstand struck up a national obsession in the 1950s, the dance show has proven perhaps television’s most perfect format. What’s not to like? Attractive, madly dressed young people play to a roving camera, showing off the latest dances along with the very Now-est sounds. It’s soothing and riveting at once, each airing locked to its own fleeting cultural moment, a pop culture kaleidoscope turning in time to a parade of hit records.

But while rapt junior American TV audiences grew up alongside their impetuous dance shows, the genre set down its own set of rules and conventions. Broadcast during just 23 weeks of 1982, and reaching no more than WCIU’s Chicagoland perimeter, The Chicago Party conformed only to those codes that suited it. Taped live inside South Side nightclub CopHerBox II, The Chicago Party did feature smooth-talking hosts in veteran musician Willie Woods and his dashing best friend James Christopher. And it let lip-synching musical guests promote their latest projects, treating Chicago audiences to dynamic performances by unjustly local artists trafficking in sweet soul, disco, and emerging electronic R&B, the pop forms then wrestling for urban chart dominance. And like other dance shows, The Chicago Party understood that—despite its own outrageous comedy sketches, bizarre variety acts, and anatomical showcases like the “Full-Figured Ladies Fashion Show”—the way to really hypnotize home viewers was to simply let the camera, and the people, gaze at bodies in motion.

Unlike most of the hundreds of shows that preceded and followed it, The Chicago Party was never shackled to a television studio’s mannered artificiality. Even programs shot outdoors, like Dick Clark’s Where the Action Is and, much later, MTV’s The Grind, seemed as controlled and composed as the soundstage productions. The Chicago Party felt like it was shot at a club because it really was shot at a club. And it was fittingly disinterested in teenagers, preferring to let the CopHerBox II’s older dancers show off their experience.

Above all, The Chicago Party was real. Across town, the unpaid Soul Train gang lived out superstar dress-up fantasies; on the West Coast, Dick Clark’s American Bandstand dancers playacted their own chaste teen dreams. Meanwhile, The Chicago Party regaled viewers with a Jheri-curled ventriloquist, a black Jerry Lewis impersonator flailing rhythmically to robot prog, and rubber chicken jokes. For 23 glorious Saturday nights, Chicago viewers witnessed grown folks grooving at a functioning nightclub, dancing, laughing, and celebrating as if there were no cameras rolling at all.

But The Chicago Party aired nothing more real than the profound friendship between Willie Woods and James “Chris” Christopher. The broad-shouldered Woods attended Wendell Phillips High School in the early 1960s, graduating with a trombone under his arm. A member of the Red Saunders orchestra, Woods spent his post-adolescence at the Regal Theater, blowing behind the greatest names in jazz, R&B, and blues. Invited by Louis Satterfield, he joined Phil Cohran’s Artistic Heritage Ensemble, a group of seasoned Chess session musicians challenging themselves with progressive, conscious music. Based at the Affro-Arts Theater in Bronzeville, Cohran’s group morphed into the Pharoahs before spinning off into Earth, Wind & Fire in 1969. Woods spun differently, but remained an in-demand session and live musician, playing with Ramsey Lewis and the Chi-Lites, and in tandem ran Roosevelt University’s Upward Bound, where he coordinated college students mentoring inner city youth. In 1971, Woods became Youth Director for Model Cities, former president Lyndon Johnson’s ambitious government program for urban revitalization. At Model Cities, Woods first met the lanky James Christopher, then in charge of educational programs. A handsome ladies man with a creative flair, Christopher was also an active musician, moonlighting on the club scene as a vocalist. Soon enough, Woods and Christopher were inseparable.

“They were like brothers,” said Lacy Gray, whose sales rep work for black radio stations in Chicago led to her helping write and direct The Chicago Party. “Both had kind hearts, but they were very different. Chris was the crazy, creative type; Willie was the cool charismatic musician, but they complimented each other, made each other better. It was kind of like a marriage.”

A dynamic duo, Woods and Christopher had taken to the air long before The Chicago Party’s first engagement. Spurred by a TV flight school ad, they became licensed pilots in an era when renting an airplane and flying across the Midwest cost just a pittance. The pair traversed the States by plane, sometimes utilizing airstrips at which a black pilot touching down was akin to a UFO encounter.

Back at Model Cities, Woods and Christopher threw a culminating end of summer party for the staff at The River’s Edge, a downtown restaurant and lounge. Success with that first mid-’70s function convinced them to go into business together as party promoters, programming Saturday night dance sets. Winners at The River’s Edge, they’d next lease a club of their own, a room attached to a bowling alley at 94th & Ashland. A copper-hued color scheme was quickly agreed upon. As for a name, Christopher came up with the Copperbox, to which Woods signed on. But late that night, Christopher phoned Woods with a devilish variation. “How about,” Christopher teased, “the Cop Her Box?” They quickly commissioned local artist J. B. Cook to render a lascivious logo—a tempting nude with only a wooden crate to cover her nether regions—and the CopHerBox was in business.

In 1979, Woods and Christopher became club owners, after tricky negotiations to purchase the massive, heavily-mortgaged, and failing 69 Club at 11731 S. Halsted. For the next dozen years, the CopHerBox II reigned as one of the wildest, weirdest clubs in Chicago history, in stiff competition with Perv’s House, Burning Spear, and countless smaller lounges. In addition to sprucing up the 69 Club with disco mirrors, light-up floors, and a 1000-watt sound system, Woods and Christopher hired George Harris as the in-house disc jockey and program director. “It was a beautiful atmosphere,” Harris recalled. “No fights, no problems, and the kind of sound and lights you’d get in Vegas.”

To set itself apart, the CopHerBox II hosted campy competitions with cash prizes going to the winner of, say, the Big Butt Contest. Future radio superstar Tom Joyner put himself on the map at CopHerBox II, as host of a morning show wherein the still-open nightclub entertained surviving dancers from the night prior. A Miss CopHerBox Pageant went off without a hitch, its winner walking with cash and a fur coat. There were fashion shows and martial arts demonstrations and senior citizen social clubs before the proper club even considered restocking the bar. Gray’s work partnered the venue with radio stations, most notably WBMX, leading to an expanded vision of CopHerBox II promotion. If clubgoers could somehow see the magic happening inside at night, how could they stay away? Thus was born The Chicago Party.

At the time, local programmers got television airtime by simply securing a sponsor for the show, or paying the station out of pocket to lease a spot on the schedule. Local stations provided engineers and equipment and, should a show with potential come along, help in securing sponsorships in exchange for a cut of the revenue. Network affiliate and local VHF giant WGN was clearly outside the Woods/Christopher budget. Like many a square peg before it, The Chicago Party found a home in Chicago’s most esoteric UHF outpost.

WCIU Channel 26 was already broadcasting the Second City’s greatest, and oddest, dance shows. Founded in 1964 by John Weigel, WCIU made its mark by narrowcasting to Chicago’s ethnic communities, programming bullfights for Mexicans, A Black’s View of the News for African Americans, and Eddie Koroso’s Polka Party for Poles. Weigel’s station offered airtime to WVON newscaster Don Cornelius, who’d convinced WCIU and Sears to back his concept for an R&B variation on American Bandstand. Chicago’s Soul Train debuted on August 17, 1970, and proved popular enough with local black youth for Cornelius to launch a Los Angeles-based nationally syndicated version the following year. On the national Soul Train—with both impossibly fashionable L.A. youth and the era’s top stars of black music engaged in brilliantly funky, staccato movements—the dance show format reached its aesthetic apex. Willie Woods himself appeared in the Chicago production, which ran parallel with the national Soul Train until 1976.

WCIU, broadcasting in black-and-white until well into the 1970s, aired several less historic dance shows, including Filipino Bandstand and Attack of the Boogie. There were two all-kid dance shows. The whimsical, puppet-populated Kiddie-A-Go-Go, helmed by mod harlequin hostess Pandora, spotlighted wholesome kids, unaware toddlers, and a few uniformed Cub Scouts doing the Popeye, the Monkey, or the Swim as dictated by the spin of a determining wheel. The grittier Red Hot and Blues, produced by WPOA DJ Big Bill Hill, featured black pre-teens dancing to blues, jazz, and R&B records, with lip-synched performances by Alvin Cash, Mighty Joe Young, and Archie Bell & the Drells, among others. A live, late-night show, Red Hot and Blues kept area youths up past bedtimes, sometimes resorting to what one WCIU engineer recalled as on-air announcements to “come pick up your kids.”

But WCIU went in completely the opposite direction age-wise in 1982 when they teamed with Woods and Christopher. The station’s infamously tiny production studio on the Board of Trade building’s 43rd floor was on offer, but the CopHerBox II crew preferred to keep it in the club. And in doing so, The Chicago Party could remain unquestionably adult. Denizens of the Party were grown men and women who’d spent their days working in an office, hospital, or post office. Their show would be a joyously authentic document of real life inside a real nightclub. That it would be a bizarre nightclub was just one cherry on top: magicians took the stage as often as did beachwear fashion shows and masked swordsmen showing their stuff. A flipside to the era’s disco glitz and harrowing street narratives, The Chicago Party was the real real deal: fashionable, cool, dignified working folks, with their well-earned gray hairs showing.

Inspired by Saturday Night Live and emerging star Eddie Murphy’s visit to the CopHerBox II, organizers Woods, Christopher, Gray, and Harris brainstormed skits, mapped out the format, and booked guests. Unable to use WCIU crew at the club, they hired erstwhile dentist Andrew Kitchen’s locally owned Panos Productions. Utilizing a multi-camera setup, they set about shooting a show that would be simultaneously low budget and priceless. Despite indulging in the goofy special effects, blocky computer titles, and dramatic wipes associated with ’80s cable access productions, The Chicago Party retained a homey atmosphere all its own. “CopHerBox II was more than a nightclub, it was a community hangout where the regulars became family,” Gray explained, “and that family is what you saw on the show.”

Shot during busy Saturday nights, Chicago Party fashion shows featured the oddball designs of patron Caroline Peeples, modeled by club regulars. “Basically,” Woods recalled, “if we saw someone in the crowd who looked very nice, we asked them to be in our fashion show. This made them feel very much a part of what we were doing.” Skilled regulars themselves, The Chicago Party Dancers brought Solid Gold-type routines to an otherwise solid copper dance floor. And many musical guests were CopHerBox II partiers or had connections to Woods or Christopher. Phenix Horns trumpeter Rahmlee Michael Davis, who’d already worked with Earth, Wind & Fire, was as close to a big guest as the show ever booked; he’d had history with Woods going back to his Affro-Arts Theater days. But fame was never a prerequisite: just a demo and a willingness to lip-synch one take in front of two fairly static cameras and a live audience. Spectacular Spandex and awkwardly mimed lyrics were the order of the day.

By 1982, a Chicago black music scene that thrived in the ’60s and ’70s had seen most of the important labels leave town and many of the big recording studios specializing in R&B shutter. While Chicago producers and musicians clung to the smooth sounds that had ruled the city for decades, emergent artists like Prince, Roger Troutman, and Herbie Hancock were steering black music toward an electronic future. As The Chicago Party guests demonstrated, local producers weren’t certain how to navigate these sea changes, and the resulting post-disco boogie-funk sounds were intriguingly odd.

Odder still were the dance show’s non-musical acts. There was one Mr. Prince, a ventriloquist who’d become a South Side nightclub fixture, and the Phantom, an emaciated contortionist straight out of a Ringling Brothers sideshow. An entire installment was built around The Unknown Skater, a rollerskating phenom specializing in Chicago-style “James Brown skating,” a wheeled variation on the Godfather’s shuffling footwork performed by a guy wearing a paper bag on his head. Illusionist Walter King, who’d go on to work Vegas stages as The Spellbinder, was just a rookie in 1982, framing standard tricks with robot dancing. “When he was with us,” Woods said, “he was doing small animals—birds and stuff. Now he’s doing elephants!”

To the hosts, the most important parts of the show were their framing comedy routines, during which Woods and Christopher delighted in watching each other goof off. Thoroughly untrained, they took to gag writing and improvisation with gusto. “Willie had a comic side he didn’t even know about,” Gray remembered. “Once Chris convinced him to let down his cool and play the fool, everything clicked.”

Skits ran the gamut from a survey of patrons trying to gain club entry with fake IDs, to an almost-grim courtroom scene, in which a white judge with a thick Chicago accent convicts the hosts of a variety of absurd offenses. Some of the best material involved simple video effects: MCs were turned upside down, crushed by a descending picture border, and rattled as a camera was shaken and a smoke machine turned loose.

If comedy was the heart of the show, the dance segments were its soul. In thrilling footage, clubgoers did their thing amid genuine club lighting, surrounded by genuine club décor, shot with intimacy and precision by handheld cameras. “The angles got better and better,” Gray said. “We were learning as we went along.” Some of the best camerawork in the show’s run captured the graceful, floating couples executing smooth stepping moves in dazzling outfits, with a particular penchant for high-end men’s footwear.

“Chicago has always been known for the Bop, also known as Stepping,” Woods offered, “which is a cool dance. People look to Chicago to see how it’s really done.” Big, flashy, legendary Chicago stepper Charlie Green moved with the energetic grace of a sprite and an enchanting sense of mischief. Urban dance historians disagree about certain milestones, but it’s gospel in Chicago that Charlie Green calling “Bus Stop” at the CopHerBox II paved the way for every Casper or Cupid who has slid, shuffled, or wobbled since. Christopher and Harris sang backup on Green’s Richard Pegue-produced recording of “Bus Stop,” a local sensation disqualified from national attention by its backing track’s blatant theft of “Do It Any Way You Wanna” by People’s Choice. Green’s live calling of the line dance captured all the joys of communal dancing, as a mélange of regular-looking folks—“short guys, big girls, square dudes”—toot their booty out, do the “new wave,” revive the Twine and the Uncle Willy, and participate in ultra-cool call and response. What Chicago Party cameras caught on tape here is a true cultural treasure.

During its brief run, The Chicago Party turned the community’s eyes toward the CopHerBox II, inspired a torrent of fan mail, and earned a local Emmy nomination—which it lost to Rich Koz’s Son of Svengoolie horror movie show. Episode 20, shot on location at Lake Michigan’s Rainbow Beach, drew thousands of dancers. “It’s amazing what that TV show did for us,” George Harris remembered. “I even signed some autographs! But it made sense that it was so popular; there weren’t that many blacks on television, so all of us would watch it.”

Meanwhile, Willie Woods diligently hustled sponsorships, securing one Popeye’s Chicken ad account by playing racquetball with a franchise owner. But The Chicago Party failed to evolve into more than a promotional vehicle for CopHerBox II, funded by the club’s proceeds. “It became a lot of work,” said Gray, “and the money was just not there. We still had our real jobs, and this became a whole ‘nother job.” After a July 31, 1982, installment featuring swimsuit competitors and a Central Power System performance taped weeks earlier, production ceased and the Party was officially over.

“Several years after doing the TV show, we started thinking about saving money to redo the club,” Woods said. “We were going to make it into something totally different. But in order to really make that money back we had to stick around, another ten, fifteen years. And we didn’t really want that anymore because the scene was changing. People were becoming more violent in the streets, and we started to see a little bit of that sneak into the club.”

Finalizing the 1991 sale of their club took years, and sadly, just one half of the original partnership was around to reap the rewards. James Christopher died in 1989 while driving back from a visit to his fiancée in Warren, Ohio. A semi-trailer jumped the median and struck his car head on. In the long aftermath, Woods wished he could’ve convinced his friend to pilot a plane to Ohio. And though the building that housed the CopHerBox II was ultimately bulldozed by new ownership at State Farm Insurance, Woods took comfort that his good friend James Christopher’s exploits inside 11731 S. Halstead had been preserved by ¾” U-Matic videotape.

“If you don’t have anything documented you become an urban legend,” Willie Woods said. “But now these things are here for the next generation, so they know there was a time in Chicago when young folks and elderly folks came together and they partied and they had fun. These are people who should have been chronicled because they were at the top of their art. The Chicago Party did that for them.

-Jake Austen, August 2014

JESUS WAYNE

The Chicago Party’s theme music was in the making long before Willie Woods and James Christopher secured airtime on Channel 26. The song’s author, Jesus Wayne, appeared at separate intervals in the lives of the two promoters, first in the early ’70s when Woods was still blowing with the Pharaohs, and later at the decade’s end via the Model Cities program, where Jesus’ brother Eddie was trying his hand at urban renewal. When Jesus walked a Woods/Christopher-hosted party at The River’s Edge, he was surprised to see the two familiar faces standing shoulder to shoulder. As The Chicago Party neared its first taping, Wayne was the consensus choice to pen the theme.

As a 12-year-old, the talented Jesus Wayne Stephens was already auditioning material at Brunswick’s South Michigan Avenue studio. Upon graduation from John Marshall High School, Wayne served a tour of duty with Chicago’s torrid Boscoe ensemble before forming his own Thunderfunk Symphony. At his side was prolific arranger Sonny Sanders, who’d spent the last decade writing hits for Mary Wells, Jackie Wilson, and Tyrone Davis. Fronted by vocalist Keni Rightout, the Thunderfunk Symphony featured Wayne on keyboards, Chico Freeman on sax, Steve Galloway on trombone, Rahmlee Michael Davis on trumpet, Kenny Elliott on drums, and Kerry Richmond on guitar. The Symphony signed to Carl Davis’ budding Innovation II imprint, cutting both “Forty Days (& Forty Nights)” b/w “Time To Discover” and “Sky Blue” b/w “Hard Times” in quick succession. But when squabbles among members crescendoed at decade’s end, Wayne disbanded his Symphony, next to try his hand at conducting himself.

As the decade turned over, Wayne was on something of a roll. Under his belt were two AVI-labeled EPs and several song placements for MCA, Sutra, Parachute, and Salsoul. For The Chicago Party theme music, Willie Woods approached Wayne with a seed lyric: “We are the party people and this is where we gather.” Wayne cobbled together the rest in the studio. Judging by the lyrics “We’ll fill your heart with laughter,” The Chicago Party may’ve been intended to be as much Saturday Night Live as Soul Train. Recording session details remain foggy, though the track’s slap and pop put bassist Charles “Chuck-A-Luck” Hosch at the scene of the crime. The show’s eventual closing credits reveal Wayne, Lacy Gray, and James Christopher as the song’s backup singers. Though his music kicked off and shut down every episode—and the Center Stage, New Testament Band, and Donnell Pitman all performed his compositions for the show—Jesus Wayne never did appear in person on The Chicago Party.

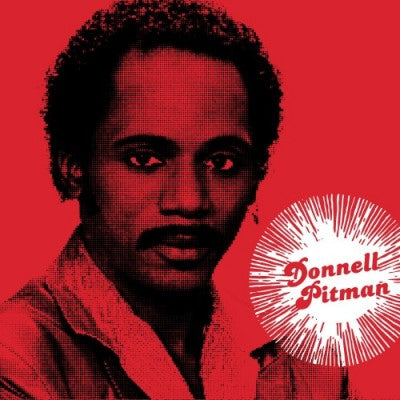

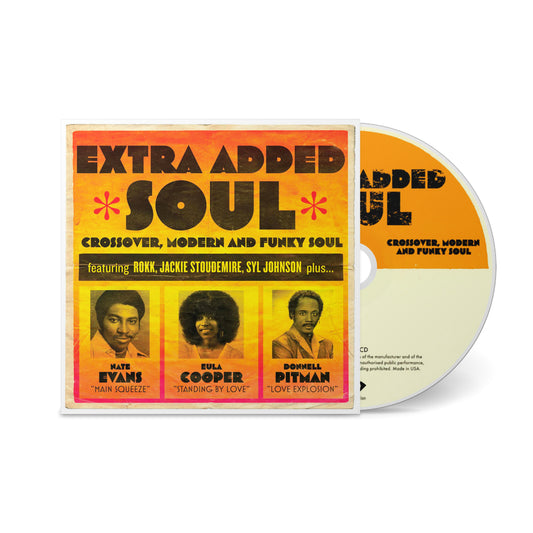

DONNELL PITMAN

Born in St. Louis and raised in rural Cairo at Illinois’ extreme southern tip, Donnell Pitman arrived in Chicago in 1967. His first group, the Soulful Squares, consisted of neighborhood pals John Hill, Melvin McFadden, Roosevelt Johnson, and Lawrence Johnson. In need of a demo, they contacted Eugene Alexander at Parliament Studios, an aspiring songwriter with an eye on building an empire. Alexander contributed his own “You Hurt Me” and “I Don’t Even Know” to the recording session, alongside Pitman’s “The Girl Next Door.” The Dean label, named after Alexander’s girlfriend, served as Parliament’s house label, and its blue-labeled “You Hurt Me” 45s obfuscated the Soulful Squares’ involvement altogether, crediting the disc solely—and quite mistakenly—to a “Darnell Pittman.”

Pitman briefly served time in the mid-’70s as a Majestic Arrow under the direction of infamous Chicago bandleader and Bandit label proprietor Arrow Brown, before catching the ear of local promoter Archie Russell. Pitman left Brown’s cult and connected with Synergy, another Russell client. The team cut 1981’s “More People Than Me” b/w “Can You Feel It” for JBP Records; the 45 and 12” would be Pitman’s only work with the group.

Russell then tapped recent Thunderfunk Symphony casualty Jesus Wayne, who donated multi-track sessions for his recently orphaned compositions “Taste” and “Burning Up.” Willie Woods’ work as Synergy’s trombonist and Jesus Wayne’s theme song contribution to The Chicago Party made Pitman’s performance of “Burning Up” on Episode 7 of the show an inevitability.

Further into 1982, Pitman was tasked with penning words for an instrumental produced by Russell and Floyd Smith at PS Studios. Adrift in a sea of writer’s block and glued to an episode of The Love Boat, Pitman noted the words “Love Explosion” in bright lights over the deck of the namesake vessel. Block broken, Pitman let loose lyrics of gushing disco plenty for the Russell/ Smith dance floor anthem. The second half of the ’80s saw Pitman releases concerning dynamite, candy, and chocolate on New York’s After Five imprint, but nothing ever topped “Love Explosion” for Donnell at his most combustible.

YVONNE GAGE

While Yvonne Gage’s family was not musical, everything from Sarah Vaughan to Motown coursed through the Gage’s Chicago household via a well-calibrated stereo courtesy of Yvonne’s electronics repairman father. Midway through the 1970s, 14-year-old Yvonne joined her first singing group, the Soulettes. Membership of the Soulettes had included a host of Lawndale neighborhood talent since releasing “It’s Alright” b/w “Find Somebody New” for Bo Dud’s Dud Sound label earlier in the decade. Comprised at the time of Patricia Redmond, Marion Robinson, and Adeline Robinson, the quartet was managed by Robert Tabor, who groomed the group, helping to advance each individual vocalist. After adding Marcella Willis, Tabor changed the group’s name to Love. He then brought the quartet to Chicago arranger Donald Burnside, who was creating a national buzz writing for AVI recording artist Captain Sky. An opportunity to tour behind Burnside and Sky’s 1979 album Pop Goes The Captain pulled her away from the group, and set her on a path towards The Chicago Party.

Upon his return to Chicago, Burnside trained his focus on writing and recording material for a Love-less Yvonne Gage. New York native and disco veteran Raymond Francis Caviano signed the promising vocalist to a single deal on his own RFC, an imprint of Atlantic. As “Garden Of Eve” grew from sketch to fully-orchestrated disco masterpiece, Gage spent day and night at Paul Serrano’s P.S. Studios at 323 East 23rd Street. By 1981, RFC was churning out dance-floor gold and Gage’s single took root amongst other popular releases by label mates Gino Soccio, Change, and Suzy Q. In 1982’s winter, “Garden Of Eve” flowered on the disco charts, peaking at #36 on Billboard’s Disco Top 60. Gage prepped seriously for full-blown stardom, donning braces for her appearance on The Chicago Party, Episode 2. Several potential follow-ups to “Garden Of Eve” were put on ice as calls to Caviano got less and less frequent returns. Gage signed to CBS in 1984, releasing her full-length debut Virginity on the Chycago International Music imprint, replete with Yvonne in fur and lace on the cover and a flashy sticker to hype “Doin’ It In A Haunted House.” Sadly, the none of the ghosts from “Garden Of Eve” were around to scare up airplay, and the record died in the basement.

RAHMLEE

By Willie Woods’ estimation, Rahmlee was the biggest star featured on The Chicago Party. Against the show’s roll book of local legends and minor celebrities, Rahmlee’s lengthy track record does seem to place him at the head of the class. Son of Chicago jazz pioneer Richard Davis, Michael began playing trumpet at age ten, his interest and abilities intensifying through graduation from Wendell Phillips High. While holding off on a music scholarship from Malcolm X College, Michael’s band Pieces of Peace quickly molded itself into the Brunswick Records wrecking crew, performing on all relevant titles by Barbara Acklin, Gene Chandler, and Tyrone Davis, and moonlighting for Dakar and Curtom as opportunities arose. Eventually, Pieces of Peace begat the Pharaohs, which in turn begat Earth, Wind & Fire. And that EWF horn section—Don Myrick on saxophone, Louis Satterfield on trombone, Michael Harris on trumpet, and Michael Davis on trumpet—developed itself quite a reputation. By the time Davis cut his first solo record in 1972—a two-part take on Leon Russell’s “This Masquerade”—he’d adopted the moniker Rahmlee, a name bestowed upon him by villagers during a Pieces of Peace Indonesian tour. By 1980, the four brass men had collectively rebranded themselves, The Phenix Horns.

Using the multi-tracked composition “Basin Street,” Rahmlee secured a deal for himself with Los Angeles-based Headfirst Records. Plenty of familiar names populate Rahmlee’s Rise of the Phenix roster, but none more prevalent than co-producer and keyboardist Dean Gant, responsible for almost all of the chord and bass work on Rahmlee’s seven-song debut. Such is the case on the album’s lead single, “Think,” which finds Rahmlee and Gant in musical contemplation with Average White Band’s Steve Ferrone on drums, Raydio’s Charles Fearing on guitar, former Pharaoh Derf Reklaw on percussion, and Reklaw’s wife Sylvia Cox on backing vocals. In 1981, while Earth, Wind & Fire underwent a personnel change, Genesis drummer/vocalist Phil Collins plotted his solo debut, plus a tour to match. He hired The Phenix Horns, initiating a professional relationship that helped move 1980s units beyond counting. Though 1982 found Rahmlee miming trumpet and vocal parts for The Chicago Party at local club CopHerBox II, Davis was already a year past his work on megahit Collins LP Face Value, honoring the occasion by recording the Collins composition “You Know What I Mean” for inclusion on Rise of the Phenix. Rahmlee spent the remainder of the decade deeply embedded in the chart-assaulting musical contingent that moved right on to Hello, I Must Be Going and beyond.

CENTRAL POWER SYSTEM

Led by saxophonist Nate Vincent, Chicago cover band Central Power System worked a repertoire of jazzy R&B a la Quincy Jones and Grover Washington Jr. Membership fluctuated over the years, but settled in the late ’70s on Deborah Wright on lead vocals, Aaron Jamal on keyboards, Bill Watkiss on bass, and Lewis Cross on drums. In need of a guitarist who could read music, Vincent hired Albert J. Anderson in 1979. Anderson had just released “Let’s Bounce Pt. 1 & 2” by Tiger Jack on his newly incorporated Ajana Records. A homegrown enterprise, the name combined Anderson’s initials with those of wife Andrea N. Anderson’s, while each cream-colored label offered the Anderson’s home address, 1638 East 85th Street. When Vincent decided that the band should record a single, Ajana seemed a logical choice for its release.

Tracked at several forgotten suburban studios on Chicago’s periphery, “Master’s Plan” b/w “Wondering” showcased the first and last Central Power System originals. Co-written by Vincent and Wright, “Wondering” was a breathy ballad and a tender respite from Jamal’s floor-filling “Master’s Plan.” Tiger Jack’s AJ-1001 catalog number was recycled for a few hundreds copies of Central Power System’s gospel-dusted suite.

"Chicago Party, on previous shows, has provided an opportunity for new and undiscovered talent to get TV experience and exposure,” declared James Christopher during the June 12 broadcast of Episode 16. “And this week a Chicago vocal group called Central Power System will entertain you.” Bedecked in black suits and sequined ties, the group went through the motions of “Master’s Plan” with Jamal mimicking his piano parts on a Moog synthesizer, Vincent standing in for a large horn section, and nary a bass player to be found. Not until the closing moments of The Chicago Party finale on July 31 did producers air the group’s performance of “Wondering.”

But inexplicably, Vincent prohibited the live performance of either side of the Ajana 45, and so Central Power System stock gathered dust in Anderson’s basement. Frustrated, Anderson left the group to focus on his label, publishing company, and songwriting partnership. After that, Central Power System morphed into Nate Vincent and the Central Power System, before the bandleader eventually pulled the plug on the whole organization.

CLOSENCOUNTER

When Closencounter landed at the CopHerBox II in April, 1982, Bob Amos sang lead, Avis Elkins sang 2nd Tenor/Baritone, Tyrone White sang 1st Tenor, and his brother Extavier White sang, as he put it, “Anything you want me to sing.” On-air host Willie Woods took the offered bait and ran a bit: “Now that’s the kind of guy I like,” he proclaimed to the audience. “Can sing it all.” A Southside quartet, Closencounter had met the lone criterion set by The Chicago Party for its musical guests: to have recorded music. Tracked at toney Universal Recording in Chicago’s Gold Coast and mixed by Donald Burnside at Paul Serrano’s P.S. Studios, “Let Yourself Go” b/w “Magical Moments” would be the lone entry in the Dapper Records catalog, despite the lofty implications of its 101283 catalog number. In the early ’80s, Burnside practically lived at P.S. Studios, and so retains little information about one of countless local upstarts to cross his mixing console. Songwriters Karl Denwood and Lisa Caillouet recall nothing about the vocalists, much less how their compositions got in the group’s hands. Though they’d begun in high school penning songs for a musical presentation of “Jack & The Beanstalk,” Denwood and Caillouet display little of their off-off-way-off Broadway beginnings in their sole released work.

Whether the “Let Yourself Go” 45 help leverage their Chicago Party slot or not, Closencounter ditched the song in favor of the never-released “Without Your Love,” suspected to be a repurposed version of “Thinking ‘Bout Your Love” by local arranger and violinist Edward P. Green III. The aspiring arranger had already left for Los Angeles by the time Episode 8 of The Chicago Party aired, though he’s reasoned that his own songwriting partner Stephen Harris might have supplied Closencounter with the multi-track session and lead sheet. In any case, period photography does linger on to preserve a few magical Closencounter moments: the red-jumpsuited quartet leaping at once in a tree-lined field; and posing before the drop cloth in lightning bolt tuxedos; and on stage, working out the sky-blue numbers they chose for their encounter with Chicago’s TV viewership.

UNIVERSAL TOGETHERNESS BAND

While passing through the Columbia College cafeteria in the spring of 1979, Chicagoan Andre Gibson spotted an engineering department flyer announcing a search for bands to serve as specimens for aspiring recording majors. With studio time at both Universal Audio and Zenith/dB hovering at around $125 per hour, free recording sessions were too good for Gibson’s extracurricular group, the Universal Togetherness Band, to miss. Drawing membership from a few chapters in Gibson’s life, Universal Togetherness Band was comprised of identical twins and Illinois State alums Fred and Leslie Misher on bass and guitar, Andre’s younger brother Arnold on drums, and fellow Columbia student Paul Hannover blowing the harmonica and tickling the 88s.

As the Universal Togetherness Band filled reels of magnetic tape with their eccentric dance music, their inexperienced manager Antoinette Stern shared the results with acquaintances at Mercury Records, and steadily booking the group across the Windy City. When Mercury closed down their Chicago office in 1982, the Universal Togetherness Band was left with dozens of fully realized tracks, some of which they’d hoped might land on their major label debut deferred.

The band’s own togetherness was already being sternly tested when, in July 1982, James Christopher caught them at So Rare Dinner & Supper Club at 87th & Throop. He sold Andre Gibson on a Chicago Party appearance. During their presentation of “Pull Up,” Hannover pretended to play an unplugged electric piano and Andre faked it on the guitar. Stand-in bassist Willie James mimed the lines Arnold had tracked at Universal, while true bassist Arnold Gibson reenacted a drumbeat previously tracked by Misher. What better metaphor for a group in disintegration than a make-believe performance of an unreleased song on a public access TV show just weeks away from its own cancellation?

MC²

Roosevelt Jamil Williams arrived in Chicago in 1977 by way of Baton Rouge, Louisiana, where he’d studied at Southern University’s jazz institute under founder Alvin Batiste. A native of Mississippi, Williams had an aunt and uncle at 55th & Morgan in Chicago’s Hyde Park neighborhood, who offered the aspiring musician room and board until he could get situated. After work at Chicago Cultural Center, Williams hung out at the High Chaparral at 77th off Stony Island. There he met bandleader Ron White, and later joined his group Secrets in 1980. As Secrets, Williams, Kevin Mays, Keith Rozier, and Kenny Davis spent untold hours at Paul Serrano’s P.S. Studios, demoing songs during off-peak timeslots and moonlighting on whatever other sessions availed themselves. But when a dedicated Secrets record failed to materialize, Williams left the group.

By 1982, Williams had married Wanda Howard Williams, and his brother Robert had left Mississippi to join him in Chicago. MC² formed around Wanda and Maria “Maya” Tate on lead vocals and Robert on trumpet, plus Eric Venable on bass, Spencer Daniels on guitar and his brother Michael Daniels on keyboards, Tony Miller on drums, and a dancer named Joy Gonzales. Cover material culled from the catalogs of the S.O.S. Band and Heart featured Wanda and Maya singing in unison, as did much of MC²’s original material, including “Blow Me Away.” That song had been in Williams’ repertoire since he’d become a Chicagoan, and he’d updated it now and again to suit contemporary tastes. MC² hosted a weekly production at its practice space at 1313 South Michigan Avenue, catching the attention of Gerald Sims, whose Gerim Records was headquartered just few blocks away at 2120 South Michigan Avenue, in space formerly occupied by Chess Studios. “Blow Me Away” was issued in both 12-inch and 7-inch formats, with a bilingual intro split evenly between Williams and Gonzales. While Williams delivered the vocal on Gerim’s “Blow Me Away,” it was Wanda and Maya who pantomimed yet another recorded incarnation of the group’s malleable single for The Chicago Party, episode 10. Bedecked in pink boas and sparkly superhero-style leotards, MC² and “Blow Me Away” ultimately failed to kick up much dust in any of its manifestations.

THE CENTER STAGE

In the halls of Chicago’s Marshall High, vocalists Keni Rightout, Ronald Christian, Kirk Davis, Greg McEastland, and William Ledbetter formed the Dimensions in the early 1960s. In 1965, they came under the tutelage of up-and-coming writer/ arranger Barry Despenza, who renamed the quintet the Traits. The group’s recorded debut, “Some Day, Some Way” b/w “You’ve Waited To Long,” became a regional hit for Despenza’s Contact label in 1966, prompting the follow-up “Need Love” b/w “Someday Soon.”

As acts began phasing out pluralized group names, Despenza suggested The Center Stage, while the band swapped in Willie Riley for the outgoing Ronald Christian. To familiarize fans with the updated brand, The Center Stage’s planned an adaptation of “Some Day, Some Way” as a first release. What’s more, Despenza commissioned a young Donny Hathaway to arrange “Some Day, Some Way” as well as “Hey, Lady.” On the strength of their inspired two-sider, Despenza signed The Center Stage to RCA, forging each member’s name on the contract and fleeing with their advance. “Some Day, Some Way” b/w “Hey, Lady” got an RCA pressing in the fall of 1971, but Despenza wasn’t around to celebrate.

Lead vocalist Keni Rightout proved to be The Center Stage’s breakout member, forming the Thunderfunk Symphony in the mid-’70s with childhood friend and composer Jesus Wayne, trumpeter Rahmlee Michael Davis, and several other notable locals. In 1981, Rightout released a 12-inch single on disco giant Salsoul Records, boasting two Jesus Wayne compositions, “Right Now” and “Out Of Sight.” His hustling, singing cousin Larry “Demetrius” Jackson appreciated Rightout’s trajectory and suggested bringing the Center Stage moniker out of retirement. With former Dimension Ronald Christian back in the fold, the trio booked time at Marty Feldman’s Paragon Studios at 9 East Huron in Chicago’s Streeterville environs. The Center Stage hammed their way through both recordings—Jesus Wayne’s “Jam” and Ronnie Miller’s “Lovin’ Time”—on The Chicago Party (split between episodes 13 and 22), donning their silver, pink, and blue lamé jumpsuits. After an unsuccessful audition with Carl Davis’ Chi Sound Records, The Center Stage made its final curtain call in 1983.

I.N.D.

Gary, Indiana’s own I.N.D.—an abbreviation for Into New Dimensions—bore a striking resemblance to Gary, Indiana’s own Krash Band, the female-fronted crew that produced 1976’s “Pickled Bees Knees” b/w “So I Can Make This Change (In My Life)” for Liberated Records. With a new bassist and an additional guitar man, the newly christened Into New Dimensions caught the attention of a trumpeter/producer known as Gene “Bow-Legs” Miller. A native of Memphis, Tennessee, Miller was curating a label on behalf of three medical doctors who fancied themselves fit for the record business. Having released a few of his own singles on Hi Records in the late ’60s, Miller booked time with Willie Mitchell at Royal Studios. Despite this flirtation with R&B royalty, I.N.D.’s debut 45 “I’m Not Ready” b/w “You Just Be You” ended up as the first and last entry in the Momisey Records discography.

Back in Gary, I.N.D. caught wind of a new label in nearby Merrillville, just ten miles due south of their northwest Indiana hometown. Founded by Joe Sotiros and Jim Porter, Erect Records boasted a mixed bag of Grecian hard rock and R&B releases in its upstanding catalog, befitting the tastes, respectively, of both owners. I.N.D.’s self-titled debut LP, with its dimensionally enhanced cover logo, materialized in 1981. Its single, “Everybody Likes To Do It,” saw two issues: a 12-inch backed with “Spyrm Of The Moment” and a 45 mix, backed by “Into New Dimensions.” Promotional copies of the album were sent to radio stations throughout the Midwest, leading several jocks to select standouts from the respectable lot. The melodic and mid-tempo “Side By Side” seemed to resonate most with Chicagoland selectors, and it was that song that the group performed for Episode 14 of The Chicago Party.

THE HARVEY-ALLISON EXPERIENCE

As a 6th grader in 1964, Ken Allison entered the music business by promoting a concert celebrating his parents’ 11th wedding anniversary. The headliner was Ken’s uncle Luther Allison, already canonized among the greatest of Chicago blues guitarists. As musical role models came and went, the impressionable younger Allison stuck with Elvis Presley, having witnessed the Tupelo native’s rise from honky-tonk obscurity to complete package. The entrepreneurial Allison took inspiration from Elvis’ ability to draw a paycheck at multiple junctures of the music business.

A newly enlisted Marine in 1971, Allison honed his vocal abilities via USO tours throughout the Pacific. Returning to Chicago in 1973, Allison reunited with Curtis Johnson, a former Chicago Vocational School instructor who’d begun mentoring aspiring talent through his extracurricular production company, Ice Entertainment. Allison would warm crowds at the High Chaparral, priming patrons for David Ruffin, the O’Jays, and the Stylistics. Noting that a performer’s take was relatively meager compared to the pie slices awarded to promoters, managers, and non-musical personnel, Allison formed Truth Productions in 1977 as a vehicle for his singing career and that of others who lacked representation.

To demonstrate Truth Productions’ original output, Allison booked a few weeks of studio time at Ye Olde Sounde Shoppe with former 24-Carat Black organist and studio owner Bruce Thompson. Compositions by a younger Allison had tended toward the romantic, but the Vietnam era and Allison’s role within it brought political motifs to his pen. Recorded in January of 1979, “Freedom (Sweet) Freedom” and “This Is Our Love Story” perfectly represented Allison’s modes. “Freedom” was a poetic account of how all creatures, from butterflies to human beings, have the right to be free, while “Love Story” was a sentimental conversation in metered rhyme between Allison and Truth Productions star Diane Harvey. A summer release in ‘79, “Love Story” eclipsed “Freedom” thanks to Tyrone Kenner Jr.’s broadcast repetition of the tender duet on Gary, Indiana’s WBEE radio.

Through the early ’80s, most functions hosted by Truth Productions featured Allison and Harvey in equal measure, with each concert culminating in “Love Story.” During a Saturday brunch at the CopHerBox II in 1982, the Harvey-Allison Experience caught the eye of club owner James Christopher, who invited the duo to lip-synch the tune for Episode 20, filmed at Rainbow Beach. Although Woods forecasts the group’s appearance during the episode’s intro, “This Is Our Love Story” was issued a rain check, reincarnated at the CopHerBox II for Episode 22.

THE NEW TESTAMENT BAND

In Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood, the intersection of 43rd Street and Forrestville is hallowed ground for New Testament Band’s founding class. Comprised of Forrestville High singing students Anthony Thomas at lead and 1st tenor, Maceo Thomas at bass, Cornelius President at lead and tenor, Richard Weddington at 1st and 2nd tenor, and Reggie Cotton at 2nd tenor and baritone, the vocal quintet’s break came in 1971 by way of People’s Gas employee Arthur Dubois, who approached the teens about cutting a record. Dubois called in a favor to the Pharaohs, who backed the newcomers for a session at Les Tucker Studios. Co-written by future Earth, Wind & Fire trumpeter Don Myrick and saxophonist Fred Walker (Derf Reklaw), “Dig It (Shovel)” was accomplished in one take, as was “Blowin’ With The Wind,” and the two sides were issued on Dubois’ Tiki imprint credited to the Intentions. Just as Intentions 45s were being pressed, Dubois caught wind of a series of minor infractions that included members wearing band uniforms on dates and severed ties with the quintet.

After graduating from high school, a few Intentions began commuting to suburban Aurora, Illinois, where the keyboardist from their former backing band, From The Womb To The Tomb, had secured a church gig. Cutting their teeth behind the pulpit, the group adopted The New Testament Band as its handle. The group swelled and membership fluctuated, settling finally with Reggie Cotton on lead guitar, Andre Cunningham on rhythm guitar, Reggie Crawford on bass, Kevin Walker on drums, and a robust horn section featuring Gary Patton on saxophone, Steve Maylor and Michael Erby on trumpet, and Darryl Creasy and Johnny Cotton on trombone. They secured the managerial services of James Thomas, who got the group increasingly profitable gigs opening for the Dells, the Chi-Lites, and the Isley Brothers at the Arie Crown Theater. Thomas secured a recording opportunity at Sky Hero studios and enlisted songwriter Jesus Wayne to contribute a potential hit. The session would yield Wayne’s “Say Yes” and a collaborative “Get Testa-mized.” Sky Hero issued the resulting 45 on its in-house label, while the New Testament Band etched the song pairing a place on its own Tablet imprint. The romantic “Say Yes” had potential, but two songs by the same name were issued almost simultaneously by major players Lakeside and the Whispers—New Testament Band would’ve needed a miracle. Instead, Louis Satterfield caught the group at a Southside nightclub, and introduced Thomas to Willie Woods, who slotted New Testament Band into The Chicago Party’s 11th installment.

MAGNUM FORCE

Vocalist Nate Williams, organist Rory Sizemore, and his bass-playing brother Edric “Ricky” Sizemore became musically associated as teens, playing together in the church. With a growing curiosity in secular music, the trio began developing original material with the intention of circulating demos to regional labels. Operating informally as Seville, “Share My Love” became both thesis statement and title track for an album project facilitated by producer Carl Davis. Newly aware of Millennium Records signees Seville in New York City, Davis suggested the name Magnum Force to Williams and the Sizemores, who Davis then signed to his own Kelli-Arts Records. Headquartered at 8 East Chestnut on Chicago’s Near North Side, Kelli-Arts issued “Share My Love” as a B-side to both “A Touch Of Funk” and “Are You Ready For The Weekend,” both available on 45 or 12-inch.

Adding to the Force were vocalist Dwayne Liddell, Stanley Winfield on guitar, Mark Bynes on saxophone, Carl Homer on trombone, and Myron Robinson on drums. As colorful musical guests on the debut episode of The Chicago Party, Magnum Force donned dazzling red tops, tight black pants, and bright white shoes. When host Willie Woods asked Rory Sizemore about his group’s label, panties melted audibly to Sizemore’s syrupy baritone: “Okay, we’re currently up under Kelli-Arts Records.” Amid swooning audience catcalls, Woods asked incredulously, “Where you get that voice from?” He then turned to the crowd with his best Sizemore impersonation to confess, “Wish I had a voice like that.” Choreographed dance moves suited the throwback sound of “Share My Love,” while its namesake album boasted an upbeat and down-tempo mixed bag. In 1982, “Girl You’re Too Cool” was the last album cut immortalized as a 12”, mixing Magnum Force’s vocal gifts and dance floor awareness into one seemingly perfect single. As house music’s influence began to intensify within Chicago’s music scene, Magnum Force chimed in, achieving six-digit sales figures in 1984 with their single, “Cool Out” for Shreveport, Louisiana’s Paula Records.